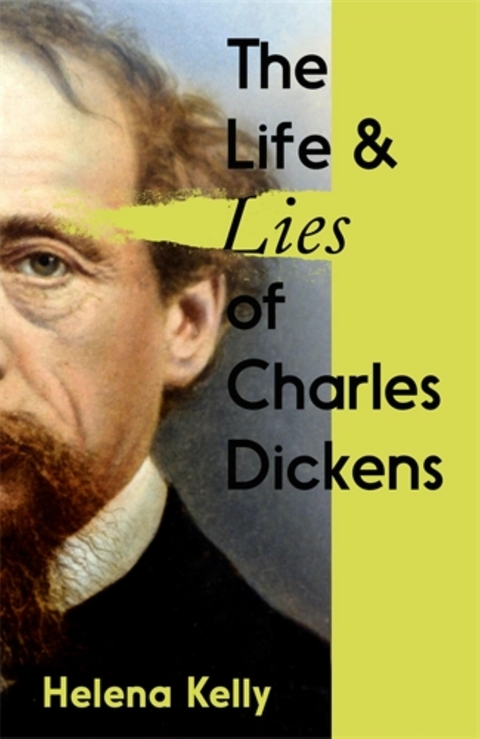

The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens (eBook)

320 Seiten

Icon Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-83773-113-8 (ISBN)

Helena Kelly holds a doctorate from the University of Oxford, where she has taught classics and English Literature. Brought up in Kent, she now lives in Oxford with her husband and son. She is also the author of Jane Austen, the Secret Radical and The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens.

Helena Kelly holds a doctorate from the University of Oxford, where she has taught classics and English Literature. Brought up in Kent, she now lives in Oxford with her husband and son. She is also the author of Jane Austen, the Secret Radical and The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens.

PROLOGUE: THE CONJURER AND THE CONJURER’S ASSISTANT (1843)

The weather has been exceptionally mild of late but in this Christmas season every party demands a good blaze and good cheer. What with the fire and the punch bowl and mounting excitement, they are all already too warm; the children pink-cheeked, the ladies, both young and older, hectically flushed. Mrs Dickens, so near her time that none of the married women think it altogether wise for her to have come, sits breathless and smiling, dabbing at her brow. As for the gentlemen, one or two of them are growing so very boisterous, so shiningly rubicund, that it seems not impossible they might drop dead of an apoplexy and ruin poor Nina’s thirteenth birthday party – and almost certain that not all the glassware will survive the evening intact.

The hostess, Mrs Macready, whose actor husband is away on tour in America, grows fretful. The gentlemen are her husband’s friends, for the most part, and kindly meaning to fill her husband’s place, but how is she to control them? All these sticky-fingered children, her pretty rosewood tables, everyone growing impatient. How long are they to be kept waiting?

But there are promising signs at last – a head peers around the door, conversations fade, noisy masculine voices demand quiet, a wine glass is rung, a bawled cry of Order! and their evening’s entertainment bounds into the room.

Dickens is brilliant, of course. He pulls coins from behind the ears of the birthday girl and magics up sweets. He burns a handkerchief and then draws it out from a wine bottle, unsinged. Will anyone lend him a pocket-watch? In a flash it vanishes, only to be discovered inside a locked tea caddy. He conjures a guinea pig, which gets loose and scurries about the floor, squeaking furiously, fur on end. He kindles a fire in a hat, sets a saucepan over it and – in no more than a minute – has turned raw eggs and flour into a hot plum pudding and shows off the inside of the hat, good as new. Everyone is amazed, astonished. The room rocks with laughter. There is a storm of applause.

Dickens bows, delighted.

His friend John Forster fetches and carries and holds the props.1

You may think that you know all there is to know about Charles Dickens – and there have been so many biographies and biopics devoted to him, so many newspaper stories, that you can be forgiven for thinking so. John Forster may not be a name you’re very familiar with, though, but if you’re interested in Dickens you really should be.

The two men seem to have met towards the end of 1836, introduced by a mutual acquaintance, the novelist William Harrison Ainsworth.2 They hit it off. Invitations and gifts of magazines quickly followed their first meeting.3 By June 1837, Forster was helping Dickens in a contractual dispute.4 From then on, for almost the entirety of Dickens’s career, John Forster was there in the background, dealing with the practicalities, prompting and advising. Nowadays we might call him Dickens’s literary agent. It was to Forster that Dickens usually confided new ideas and complained when his writing wasn’t going well; Forster who read his first drafts and negotiated on his behalf with publishers. They socialised and holidayed together. Few other relationships in Dickens’s life proved so enduring. While friends and business associates and even close family members were left rejected by the wayside, Forster remained within the circle of trust. Dickens may have taken up with other intimates, such as fellow novelist Wilkie Collins, but when he separated from his wife Catherine in the late 1850s, it was Forster he chose to negotiate terms for him. And Forster was the person Dickens selected to safeguard his manuscripts after his death.

The two men were close in age. Both, after toying with legal careers, turned their energies to literature, though with markedly different success. Forster was chiefly a bread-and-butter writer – a journalist, a critic, occasionally a biographer. In later life he also worked for the Lunacy Commission and acquired – most unexpectedly – a rich wife. He had a remarkable talent for getting close to other, more celebrated literary figures. While still a young man he befriended Charles Lamb (of Tales from Shakespeare fame), the poet Robert Browning, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who was a best-selling author in the late 1820s and 1830s.5 He also became engaged to a then wildly famous poetess called Letitia Elizabeth Landon, known by her initials L.E.L. A decade his senior, with a spotty reputation, she eventually broke off the relationship and married another man.6 Nor was Dickens the only author he represented.

Unlike modern literary agents, Forster didn’t get a contractually agreed cut of any profits made by his writer friends. What motivated him, then, if it wasn’t money? What hunger made him pursue, for decades, the role of unpaid helper and occasional conjurer’s assistant?

Perhaps what those who befriend celebrities so often want: proximity, access, inside knowledge.

That, anyhow, is what everyone assumed Forster had managed to get. The first volume of his The Life of Charles Dickens appeared in 1871, eighteen months after the novelist’s death, and the third and last volume in 1874. People might have joked at the time that the book ought more properly to have been called ‘The Life of John Forster, with reminiscences of Charles Dickens’, but they read it and believed it.7 He was, after all, effectively Dickens’s authorised biographer; he was in a position to know things. His biography remains one of the most influential ever to be written. You’ll almost certainly be familiar with parts of what he wrote, even if you don’t know where they originated from. A substantial proportion of what everyone knows about Dickens comes from Forster.

For instance, it was Forster who announced to the world that sections of Dickens’s 1849–50 novel David Copperfield were pretty much straight memoir, revealing that the celebrated author had, like David, been forced into menial work as a child, taken out of school and made to labour in a boot-polish factory when his father was sent to debtors’ prison. Forster is our only source for this story, as he is for a lot of other supposed facts about Dickens’s life.

These days, though, locating and accessing archival material has become a great deal easier than it used to be. And the archives show that quite a number of Forster’s facts are incorrect, or inaccurate. He gets dates wrong, and sometimes names, too. He makes no reference to events that we now know took place. Details seem to be ignored or invented; there are people missing from the story who really ought to be there.

Is it simply that Forster wasn’t a very good biographer, or was he, instead, continuing to facilitate Dickens in the same way he’d been doing for years? While claiming to reveal the truth about his famous friend, was he actually helping to maintain Dickens’s lies, keeping Dickens’s secrets?

At the end of 1843, when Dickens performed his conjuring tricks at Nina Macready’s birthday party, he was still in his very early thirties. But since he had been hurtled to fame with The Pickwick Papers in 1836, he’d already completed four other novels, among them such runaway successes as Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and that great early Victorian favourite, The Old Curiosity Shop. A Christmas Carol had just come out. He’d spent six months of the previous year touring the United States and Canada, fêted wherever he went. His name had appeared in the newspapers thousands of times. Even those who hadn’t read any of his writing knew who he was.

But no one knew very much about him.

Take, for example, A New Spirit of the Age. This was a book of biographical essays about eminent early Victorians which was published in 1844. An essay on Dickens opened the book and the picture of him which accompanied it served almost as a frontispiece. The flattering suggestion is that he was the poster boy for the new Victorian age. The essay itself discusses his successes, to date, and his failures. It contains some sophisticated analysis of his writing. There’s one thing missing, though. The other essays in A New Spirit of the Age mention where their subjects were born, who their family were, where they went to school: this one doesn’t do any of that. We’re told that, ‘if ever it were well said of an author that his “life” was in his books, (and a very full life, too,) this might be said of Mr. Dickens’.8 Actually it’s clear that – after seven years of being a household name – Dickens’s origins and background remained, as far as the public was concerned, almost a total blank.

And despite intense, continued press interest, this state of affairs more or less persisted. Dickens’s stories were clearly often inspired by his early life – in fact, several quite unexpected aspects of his work turn out to be partly autobiographical – but he almost never wrote of his childhood without a protective veneer of fictionality, even when he wasn’t writing fiction.

In the last decade of his life, Dickens produced a number of magazine essays which look like memoirs, and have sometimes been treated so. They aren’t. There’s the ostensibly confiding piece, ‘Dullborough Town’, in which he recalls his ‘boyhood’s home’, offering details of his days...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | A.N. Wilson • Claire Tomalin • David Copperfield • Jane Austen • Lucinda Dickens Hawksley • Michael Slater • Peter Ackroyd • the Secret Radical |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83773-113-6 / 1837731136 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83773-113-8 / 9781837731138 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 669 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich