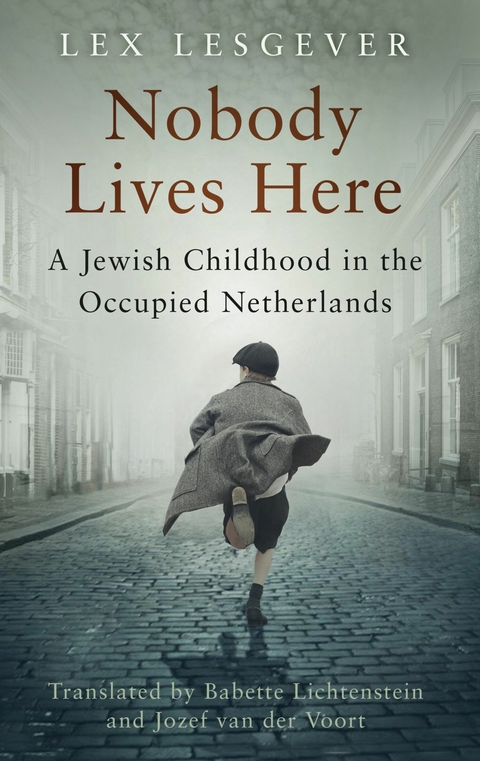

Nobody Lives Here (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-323-2 (ISBN)

LEX LESGEVER is the young Jewish boy whose story is unravelled within Nobody Lives Here, a tough, resilient individual. After his ordeal in Amsterdam during the war, he spent forty years living in Leiden where he devoted himself to the Jewish community. He died on New Year's Eve, 2019.

'I was on the street and I was free - but what now?'This is the story of Lex Lesgever: a young Jewish boy who found himself alone on the streets of wartime Amsterdam, the only survivor of his large family. He was just 11 when the Germans invaded in May 1940, and less than a year later he had already been confronted with the horrific consequences of war when his eldest brother, Wolf, was arrested during a raid. This marked the beginning of a devastating time for both the Netherlands and for the young boy who had to survive it alone. From a cosy family home in Amsterdam's Jewish quarter, to sleeping rough, escaping Nazi raids and interrogations, and being taken in by members of the Dutch Resistance, Lex's memoir pulls no punches. Witness the growth of a naive, frightened young boy into a smart, resilient and yet sensitive survivor. Painting a picture of the unfolding events in Amsterdam during Anne Frank's time in hiding, Nobody Lives Here is vivid and often horrific, but ultimately it is a poignant snapshot of humanity in its darkest moments.

LEX LESGEVER is the young Jewish boy whose story is unravelled within the book, a tough, resilient individual. After his ordeal in Amsterdam during the war, he spent forty years living in Leiden where he devoted himself to the Jewish community. He died on New Year's Eve, 2019. The translators, BABETTE LICHTENSTEIN and JOZEF VAN DER VOORT, are professionals in their field, the former also being a retired cellist and the latter presently working in the German Historical Institute, London. Babette grew up in Amsterdam just after the war and feels an intimate connection with Lex's story and able to bring colour in English to Amsterdam's streets.

Introduction

This memoir is a gripping and unusual account of a survivor of the Shoah in Holland. With impressively clear recall of his childhood and early teens – he was 11 at the outbreak of the war – Lex Lesgever writes of his years on the run and in hiding in Amsterdam and beyond. It is unusual because Lex was never deported to a death camp, but managed to escape when his family was taken, and then spent about two months on his own, mostly in Amsterdam, sleeping rough in shelters and stairwells, stealing food, trying to keep clean and, occasionally, receiving help from adults. He is caught in the middle of Nazi raids more than once – is hunted, shot at and interrogated at Nazi headquarters – and he grows ever more alert and resilient without losing his sensitivity and humanity. His many lucky and instinctively brilliant escapes are quite breathtaking, and are beautifully described through the eyes of a resourceful but very frightened child. Painting a picture of the unfolding events in Amsterdam during Anne Frank’s time in hiding, Lex’s memoir complements the reading of her diary.

Before recounting his time as a fugitive, Lex Lesgever describes what life in Jewish Amsterdam was like before the war, focusing on the long-established, close-knit, mostly working-class, loosely religious and vibrant life of Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter around the area of Waterlooplein, in which his large family comfortably took part: the Jewish festivals in the streets, the market stalls, the mutual support, the easy living alongside the rest of Amsterdam’s population. This gives a historically interesting prelude and highlights the horrific contrast with the devastating events that entirely destroyed this old way of life within such a short time.

Today’s visitors to Amsterdam are surrounded by greenery. There are trees along the canals, lavishly planted flowerbeds, wild grasses and weeds growing undisturbed between tram rails, and the inhabitants have been permitted to lift paving stones abutting their houses where flowering climbers are now growing around their front doors and up the brick walls.

It wasn’t always so. For about thirty years after the Second World War, Amsterdam was a relatively bare place. The dire need for food and fuel, especially during the Hunger Winter of 1945, had caused many of Amsterdam’s trees and even floorboards to go up in flames.

Amsterdam seemed bare in the 1950s and 1960s, but there was something else as well. People walked with their heads lowered, not looking each other in the eye. Evasion was in the air; people were wary of each other. Bullying was rife. Teachers bullied pupils, children bullied younger or weaker ones, anyone in authority bullied citizens, neighbours bullied each other. I lived there and witnessed it.

Growing up in Amsterdam shortly after the Second World War was an unsettling experience for me and my sister. My father, a Jewish musician, had left Germany for Holland in the early 1930s and had gone into hiding in 1942, at different addresses in and around Haarlem. Immediately after the war he married, and my parents spent a short period in Jerusalem before returning to Holland. They settled in the ‘old south’ of Amsterdam. We lived in an apartment on Merwedeplein, a few doors away from where Anne Frank and her family had lived before they went into hiding, also in 1942. It had been quite a Jewish neighbourhood, mainly middle class, unlike the old working-class community around Waterlooplein which Lex describes so vividly.

In the 1950s my mother told us about the war years, mainly through anecdotes, and we heard about the Shoah and about the terrible danger my father had been in, as well as the people who had saved him. But outside the walls of our apartment there was a culture of silence. The word ‘Jew’ was avoided: it was painful to say it or hear it. After reading Lex’s sober, poignant and clear descriptions of what happened to him in the streets around Anne Frank’s hiding place (and that of many others), I realised that after the war Amsterdam was a city in trauma and denial.

According to my father there had been no antisemitism in the Netherlands before the war. I didn’t believe him at the time, but from Lex’s anecdotes of his neighbourhood before the occupation I concluded that maybe my father had a point. I began to understand that where fear and terror reign on such scale and intensity for even just five years, many people begin to absorb the prevailing mentality in an attempt to cope with life.

Visitors to Amsterdam today will find the silence around its Second World War history has been broken. Studio Libeskind’s impressive Holocaust Memorial, built close to Lex’s old neighbourhood, shows thousands of names of the Amsterdam citizens murdered in the Shoah. Amongst them are the names of all Lex’s family members. The shapes of the walls of the open memorial – because of its size only clearly perceived from the air – form the three letters of the Hebrew word ‘Remember’.

Lex describes a time when all moral sense had been turned upside down; what was good or bad had lost all meaning. Grown-up men would go hunting for a single child of 13, as happened to Lex, and for much younger children too. People would be turned out of their homes and carted off. In Amsterdam, the Shoah played out with particular viciousness: the German occupation had been headed not by a military commander but by the notorious Nazi A. Seyss-Inquart, who was later tried at Nuremberg and executed. Under his cruel and ruthless rule less than 25 per cent of Dutch Jews survived the Shoah.

It struck me that Lex doesn’t name the Shoah explicitly, not with any word. The Hebrew word Shoah means ‘calamity’, which in its neutrality is a more acceptable word than Holocaust, with its ancient biblical roots in a ‘complete burnt offering’ on an altar. Maybe the best word for the unimaginable crime is ‘Churban’, used by Tony Bayfield as the title of his textbook for Holocaust education. It means ‘Destruction’, and is most often used in connection with the two destructions of Jerusalem and its Temple in 587 BCE and 70 CE.

Growing up under the cloud of this twentieth-century ‘Churban’ has coloured my outlook on life. I am of course not alone in this. Trying to overcome my fear of it, trying to understand it, come to terms with it, think beyond it, is a constant burden. I therefore had mixed feelings when Jozef van der Voort suggested we translate Lex’s memoir together. But I am grateful to him for choosing it and glad to have accepted the challenge. It is a gripping and vivid account of events we should know about and never forget. The boy who emerges from the pages is talking to us all and should become a friend to children of his age, someone they can identify with, as much as they can with Anne Frank.

Another issue which is still hotly debated, and about which Lex tells us in all his innocence of that time, is the involvement of the Joodsche Raad or ‘Jewish Council’, the body set up by the Nazis as a go-between to reassure Jewish citizens, alleviate their stress and panic, and so aid the smooth organisation of the persecution. When Lex is awaiting deportation with his mother and elder brother Max, and many others, in the Hollandsche Schouwburg, it is likely the Joodsche Raad that secures permission for the smaller children to be escorted across the road to the Jewish Orphanage where there are mattresses to sleep on. And, astonishingly in the circumstances, they are also taken for a walk to the home of someone probably linked to the ‘Raad’, where they are given hot chocolate. This outing then provides Lex with the opportunity for his first heart-stopping escape.

After his astonishing survival amid the terrible dangers of Amsterdam’s streets, Lex is rescued by members of the Dutch resistance and taken to a small agricultural community, Roelofarendsveen, where he spends the rest of the war on a farm working extremely hard and living as a member of the farmer’s family. The manner in which the whole village knows and accepts the many Jews hiding amongst them provides a thought-provoking contrast to Lex’s experiences in Amsterdam, and opens the reader’s eyes to the complicated picture of the infamous German occupation of the Netherlands.

Finally, the memoir is also a ‘coming of age’ story. Already while working on the farm in Roelofarendsveen, when the farmer is incapacitated by illness for some months, Lex, aged just 16, has to take over, work twice as hard and make business decisions. And when the war ends, he must cope with the terrible fact that not one member of his immediate or wider family has survived the death camps. He returns to the chaos of post-war Amsterdam, where he tries to rebuild his life with scant help from the authorities. After battling with illness (several bouts of tuberculosis), he recovers his health, sets up a successful business and starts a family. The last chapter in the book describes Lex’s emotional visit to a concentration camp and is a well-crafted coda to the story.

Lex Lesgever died on 31 December 2019 at the age of 90. Not until he retired did he write down his experiences during the Second World War. After the memoir was published in the Netherlands he gave interviews on radio and talked in schools about his life. Shortly before his death Lex was filmed at home giving testimony for the new National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam to be opened in 2024. Holocaust education was close to his heart. I...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Babette Lichtenstein, Jozef van der Voort |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1940 • Amsterdam • Anne Frank • Anne Frank’s diary • bart van es • dr toby simpson • Dutch Jews • dutch resistance • Holland • Jewish memoir • Lex Lesgever • life under the nazis • Nazi • nazi holland • nazi raids • Netherlands • Nooit verleden Tijd • Second World War • World War Two • ww2 |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-323-5 / 1803993235 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-323-2 / 9781803993232 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich