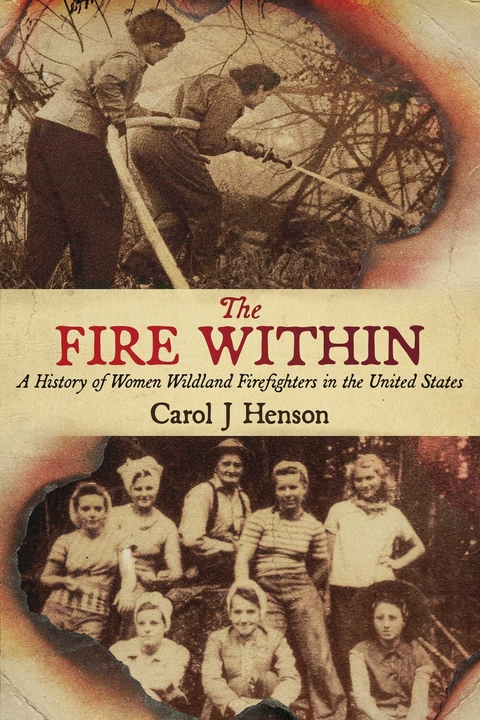

Fire Within (eBook)

320 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-1672-0 (ISBN)

It's been said that America's wildland firefighters have earned a reputation for being among the best wildland firefighters in the world. Historically considered a male-only occupation, women have a long and varied history in wildland firefighting documented back at least to the 1600s. They've served in various capacities on the fireline throughout the United States on bucket brigades, fire brigades, engine crews, hand crews, hotshot crews, smokejumpers, helicopter crews, pilots (both fixed and rotor wing), prevention, patrol, and on incident management teams. Although the story of women in wildland fire is not a new story, it is a story not yet well documented. The Fire Within is an unforgettable journey into the lives of the women who battled wildfires in our nation's forests and wildlands. It will tell the story of women who stepped into non-traditional roles to pursue their dreams of fighting wildfire, working outdoors, seeking adventure and a challenging profession, or fulfilling a sense of duty. Through their eyes and in their own voices, you will hear stories from these remarkable women. They will share who they are, why they fought fire, how they got started, how they dealt with nature's extreme elements, and how they persevered. These dedicated women, like their male counterparts, have endured 16+ hour shifts of exhausting work in extreme environments, lived under harsh conditions with long separations from home and family to protect our nation's communities and natural resources from devastating wildfires. These are their stories.

Before 1900:

Survival and Necessity

Women haven’t been written out of history; they’ve never been written in.

—Bernadette Devlin, Irish Civil Rights Activist

European Immigration and Settlement

Creates a Wildfire Problem

Wildfires became a problem soon after Europeans began settling the New World. Vast forested lands that Native people had once managed with fire—for hunting, pest control, habitat diversity, fireproofing, and clearing of underbrush for travel—was now cut and burned haphazardly to make way for farms, roads, and ever-expanding settlements.1 Wildfires became a serious threat to homes, businesses, and settlements—the first wildland urban interface fires in North America.

In 1631, wildfires destroyed homes in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. As a result, the colony passed the first wildland fire-related law forbidding the burning of any ground prior to March 1. Anyone caught burning after March 1 received serious penalties, including a fine of forty shillings and a whipping or other form of corporal punishment.2

During this time, women’s roles were primarily based on survival and necessity—not as they may have traditionally lived in their countries of origin. Most women colonists were expected to perform hard physical labor.

As more Europeans emigrated to North America, settlements and towns grew and expanded, and the women living in those more urbanized settings went back to following more traditional roles.3 However, women’s roles outside of urban settings didn’t change. In addition to handling typical household chores, pioneer and frontier women helped build their homes, took part in field work, and defended their property from wildfires.

No organized or paid fire departments existed, so fighting fires was, out of necessity, strictly volunteer. When a wildfire was discovered, citizens were responsible to sound the alarm and quickly respond to the fire.4 Women and men formed bucket brigades to douse a fire with water; used wet blankets to swat a fire; and created firebreaks using tools such as axes, brooms, rakes, and shovels. Wildland fire suppression was done solely to protect homes and communities—any efforts to protect forests or other vegetation from burning was incidental.

In the 1670s, fire pumps and fire engines were introduced.5 There were no large-scale water systems so if a water source for a fire pump and fire engine was too far away, women and men citizen firefighters formed bucket brigades to fill the water tub, and operated fire engine levers that control water flow.6

Communities were still to be ill-equipped to fight large wildfires, and losses of homes, communities, and valuable timber continued. As a result, additional laws regarding wildland fire prevention and suppression were enacted; a 1778 New York Colony law was one of the first to instruct officials to combat forest fires and summon citizens to help fight forest fires.7

Women Provided Good Service

In the early winter of 1820, a fire broke out on Main Street in Belfast, Maine. A bucket brigade in which women took their places in line received recognition for providing “good service” at the fire.”8

Seven years later, on Sunday, August 15, during a church service, Belfast’s fire alarm bell rang, warning the town that a wildfire was raging in the woods near landowner Jonathon Durham’s house on top of Wilson’s Hill. Church services quickly ended, and men and women ran to the top of the hill with a hand-carried fire engine, pails, and buckets. The citizen firefighters fought the fire, remaining until dark when they were dismissed.9

Mrs. Boyce and Her Daughter Face a Fire Tornado

On April 22, 1870, the Chicago Tribune reported that a forest fire had burned five square miles along the Long Island Railroad in Long Island, New York. The article described the sounds and sights of the fire:

The roar of the tornado of fire was heard for miles; and the heavy clouds of black smoke, now hanging lazily over the burning area, now scurrying higher and thither in lead-colored flakes at the bidding of the capricious wind, now lowering close to earth in a sombre [sic] mass too thick and too dark for the eye to penetrate, gave token to the people of the whole countryside that the destroyer who had threatened them more than once before in years gone by was upon them again.10

Boyce (oftentimes women’s first names weren’t used in old newspaper articles) and her sixteen-year-old daughter were at home alone when this fire threatened the Boyce farm. The two women grabbed whatever firefighting tools they could find and fought the fire, successfully saving their haystack. The wind suddenly switched direction, driving the fire toward a neighbor’s home. Mrs. Boyce felt comfortable that her home was safe, so she and her daughter hurried through the woods to their neighbor’s farm, the O’Neills, to help them save their home. While traveling through the woods, the wind switched again, and Mrs. Boyce and her daughter found their lives in danger from the fire. The Chicago Tribune reporter wrote, “Fire was in front of them, fire beneath them, fire to the right of them. The road was very narrow, and on the left, the safe side, so thickly grown with scrub oak and pine as to be impenetrable. They turned to go back. With a whirl and a roar, a dense volume of smoke rolled up through the woods and darkened their path.” Both women, with their soot-blackened faces, were able to safely escape the fire and found their home still standing, but sadly their neighbor’s home was destroyed.11

First Documented All Women’s Fire Brigade

By the mid-to-late 1800s, women were organizing their own fire brigades. The September 8, 1941, edition of the Gibson City Courier (in Illinois), reported that they had found a copy of an 1877 edition of their newspaper that described an all-women volunteer fire brigade in La Grange, Illinois. The women’s fire brigade was awarded a miniature silver trumpet for their efficient service in putting out what threatened to be a serious fire. It is unknown whether this was a wildland fire or a structure fire, but La Grange was a rural town where wildfires would have been a problem.12

In June 1877, another all-women fire brigade was formed at an American college for young ladies and made the news as far away as Australia. The Sydney Morning Herald didn’t specify which college or where it was located, but they reported that in America:

One of the employments in which woman is about to compete with men is (says the Pall Mall Gazette) that of service in the fire brigade. The first step of this direction has been taken in America, where, at one of the colleges for young ladies, a brigade of firewomen, or rather of firegirls, is, it is stated, in course of organization. The notion is to accustom the fair members of the brigade to exhibit the self-possession so necessary in moments of emergency, such as the outbreak of a fire, and at the same time to teach them how to act with promptitude on such occasions.13

The article went on to say that during a firefight, the fire brigade would separate into groups, and each group had its own captain and steam fire engine. The women received training in the use of the engine and would continue training until they were as “efficient at the pump as at the piano.”14

With Heroic Resolve, Kittie Lewis Battles Forest Fire

An incredible story was reported in the October 3, 1881, edition of the Chicago Tribune. In September 1881, Kittie Lewis, a young woman working as a domestic servant in Detroit, Michigan, was visiting her family in the Dwight Township on the Huron Peninsula of Michigan. Lewis’s aunt was serving as caregiver to her husband, who suffered from fever sores, and his 102-year-old mother as well as taking care of her four small children.

Although that fall was drier than normal, neighbors were burning large areas of underbrush to clear the way for crops on their farms. On Monday, September 5, 1881, Lewis watched smoke grow so thick that it darkened the sky as if it were nighttime, and she saw large burning embers and hemlock branches rain down around her family’s farm. Soon, the wood fence and vegetation in the field behind her aunt’s cabin ignited. Lewis and her aunt ran through the thick smoke out to the field to put out spot fires with pails of water, stamping out spot fires with their feet until their shoes burned away. They tore down a wood fence, trying to stop the fire’s progress. Periodically, the women drenched their clothing with water and covered their heads with wet skirts. The smoke and heat blinded their eyes, and it was painful to breathe, but the two women continued fighting the wildfire. When the shrubbery around the log house burst into flames, the women tore out burning shrubs, blistering their hands. They threw buckets of water on the house and spread wet blankets on the roof to prevent it from catching fire.

By the next morning, the fire had destroyed the family’s haystacks, barns, and outbuildings; everything was gone except for the log house. The fire was still burning, and with the well almost empty of water, the situation seemed hopeless. The two women grabbed the rest of the family and moved...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-1672-0 / 9798350916720 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,1 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich