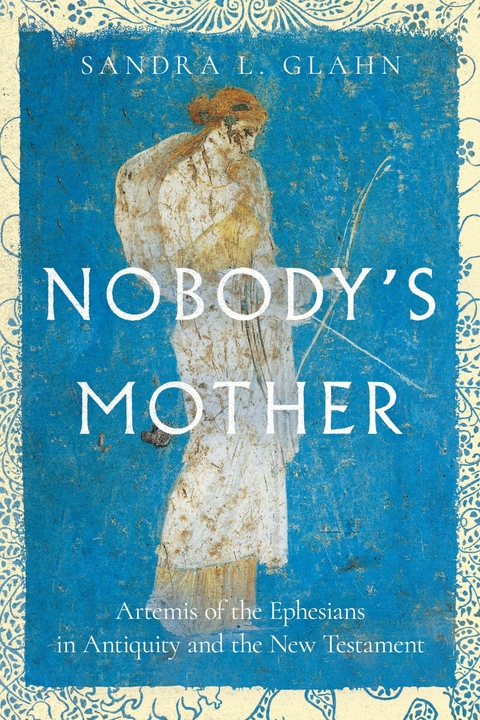

Nobody's Mother (eBook)

208 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0593-4 (ISBN)

Sandra L. Glahn is professor of media arts and worship at Dallas Theological Seminary, where her emphases are first-century backgrounds related to women, culture, gender, and the arts. She has authored or edited more than twenty books, including Vindicating the Vixens, Earl Grey with Ephesians, Sanctified Sexuality (coeditor), and Sexual Intimacy in Marriage (coauthor).

Sandra L. Glahn is professor of media arts and worship at Dallas Theological Seminary, where her emphases are first-century backgrounds related to women, culture, gender, and the arts. She has authored or edited more than twenty books, including Vindicating the Vixens, Earl Grey with Ephesians, Sanctified Sexuality (coeditor), and Sexual Intimacy in Marriage (coauthor).

AS I’VE TAUGHT ABOUT WOMEN in public ministry for two decades, I have paid attention to the most common reasons people say they consider it unnecessary to take a fresh look at the biblical text on the topic. One might expect that in a seminary the reason would be Paul’s statements about women (or wives) keeping silent in the churches (see 1 Cor 11; 14; 1 Tim 2). Yet the number-one reason I hear—maybe even especially among people with high levels of biblical literacy—is not textual. It’s historical.

For many, the narrative has gone something like this: For two thousand years, the church has held a belief and observed a practice relating to women that has remained unchanged. But the influence of the Women’s Movement in the United States has infiltrated the church, which has capitulated to culture. The idea that women can hold clergy positions and questions about women teaching biblical truth in public are new, influenced by one factor: feminism.

An author writing in Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (RBMW) put it this way when he described what he calls the historical understanding of Scripture: “This has been the view of historic orthodoxy to the present and, in fact, is still the majority view, though presently under vigorous attack. The very fact that its opponents call the view ‘the traditional view’ acknowledges its historic primacy. . . . We should begin our discussion with the assumption that the church is probably right.”1

The author does well to start with church history. The history of interpretation and practice relating to women is essential. That is why I, too, will start with it. But to be clear, the historical understanding relating to women was that “women were characterized as less intelligent, more sinful, more susceptible to temptation, emotionally unstable, incapable of exercising leadership.”2 William Witt notes a major shift from this position in recent decades: “Somewhere around the mid-twentieth century, the historic claims about women’s essential inferiority and intellectual incapacity for leadership simply disappeared. Instead, all mainline churches—Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, and Anglican—recognize the essential equality between men and women.”3 Some of the previous practices related to women have been rooted in an interpretation of Paul’s statement that the woman, not the man, was deceived (1 Tim 2:14)—part of the very text we will explore.

A narrative about the history of ideas on the subject has filtered down from the academy to the masses. Consider the words of a blogger, who wrote this more than fifteen years ago: “It was the feminist teachings of the past few decades that first spurred Christians to try to argue for [women in public ministry]. Like it or not, the two schools of thought are intertwined.”4

This is an incorrect origin story. But because such ideas so frequently shut down the topic, we will look first at the tradition. Here is a brief survey of some of the church’s most influential voices.

INFLUENTIAL VOICES

John Chrysostom (347–407 CE), an early church father who served as archbishop of Constantinople, wrote, “The woman taught once, and ruined all. On this account therefore he [Paul] says, ‘let her not teach.’ But what is it to other women, that she suffered this? It certainly concerns them; for the sex is weak and fickle.”5

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) was a theologian, philosopher, bishop in North Africa, and one of fewer than forty people named as “doctor of the church.” Many consider Augustine one of the most important figures of the Latin church in the Patristic Period. He wrote this: “[Satan made] his assault upon the weaker part of that human alliance, that he might gradually gain the whole, and not supposing the man would readily give ear to him or be deceived.”6

We see similar ideas in the works of theologians in the Middle Ages. Bonaventure (ca. 1217–1274 CE), also named as a doctor of the church, was an Italian bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian, and philosopher. He argued that only males could serve at the altar because women lacked the image of God, “but man by reason of his sex is ‘imago Dei.’”7

Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225–1274 CE) was a theological and educational doctor’s doctor. His views on male and female were deeply influenced by those of Aristotle, who saw woman as “defective and misbegotten.”8

Such ideas endured through the Renaissance. Desiderius Erasmus (ca. 1466–1536 CE) was a prominent Dutch philosopher and theologian. He said that that while woman was deceived by the serpent, man was impervious to such beguilement: “The man could not have been taken in either way by the serpent’s promises or by the allure of this fruit.”9

Of the Protestant reformers, who celebrated the priesthood of all believers, the most influential was German priest, theologian, and author Martin Luther (1483–1546 CE). Rather than seeing male mastery of the woman as rooted in the fall, Luther believed that “by divine and human right, Adam is the master of the woman. . . . There was a greater wisdom in Adam than in the woman.”10

The next generation of Reformers taught similarly. Here’s an example: John Knox (ca. 1514–1572 CE), founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, was a theologian and writer who described women as “weak, frail, impatient, feeble and foolish” as well as “inconstant, variable, cruel and lacking the spirit of counsel and regiment.”11

This is no random sampling of obscure theologians. Some tremendously influential leaders whom the church has revered through the centuries (and still does) held unbiblical views of women. William Witt, in Icons of Christ, observed: “Historically, there is a single argument that was used in the church against the ordaining of women: women could not be ordained to the ministry (whether understood as Catholic priesthood or Protestant pastorate) because of an inherent ontological defect. . . . Moreover, this argument was used to exclude women not only from clerical ministry, but from all positions of leadership over men, and largely to confine women to the domestic sphere.”12

The ontological-defect argument of traditionalists is why a segment of Christian believers in the United States began to call themselves complementarians rather than traditionalists. Unlike the men quoted above, complementarians affirm that, on an ontological level, woman is equal with man. Complementarians make the following affirmation in the Danvers Statement: “Both Adam and Eve were created in God’s image, equal before God as persons and distinct in their manhood and womanhood (Gen 1:26-27; 2:18).”13 Such a pronouncement was a break with tradition. Yet on the foundation of traditionalist views of woman’s ontology, practices for society, church, and home were built.

WHAT WOMEN ACTUALLY DID

If the practice of women serving in public leadership did not originate with feminists such as Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Bella Abzug, when did such practices start? They began before the American and French Revolutions, with their calls for freedom and individual rights. One call for women to lead was a pamphlet by Margaret Fell (later married to Quakerism founder George Fox) written in 1666. Titles were longer in her day. Here is hers: “Womens Speaking Justified, Proved and Allowed of by the SCRIPTURES, All such as speak by the Spirit and Power of the Lord JESUS. And how WOMEN were the first that preached the Tidings of the Resurrection of JESUS, and were sent by CHRIST’S Own Command, before he ascended to the Father, John 20. 17.”14 Lithographs of women preaching often accompanied such writings, depicting events that predated the Women’s Movement by two hundred and fifty years. Yet the evidence points still earlier.

The Protestant reformers in the sixteenth century emphasized the priesthood of all believers. That movement included women such as Katharina Schütz Zell, who preached at her husband’s funeral and wrote in defense of women in ministry.15 But one might notice, even earlier, The Book of the City of Ladies, written by the widow Christine de Pizan. She was born in the 1300s. Each time one explores an earlier period, the sources point back to prior sources. Here’s a sampling from earlier centuries, with the most recent first.

-

Pope Paschal I (Rome; West; ca. 822 CE)—For the Basilica of Santa Prassede, Rome, Pope Paschal I had a mosaic made of his mother, Theodora, which included a label in stone describing her as “Theodo[—] Episcopa.” Elsewhere in the church, an inscription refers to her as “Lady Theodora Episcopa.” Some tesserae in the mosaic have been replaced, removing her name’s feminine ending to make it say “Theodo[—] Episcopa.” But the matching inscription confirms the mosaic’s original wording: “Theodora Episcopa.” The word episcopa is often translated “bishop” or “elder.” If the pope identified his mother as episcopa, why would someone later change the evidence?

-

The Council of Trullo (Constantinople; East; 692 CE)—In canon 14, the council speaks of ordination (cheirotonia) for women deacons using the same term used for ordination of priests and male deacons.

Two local synods in Gaul speak of the diaconate of women for their region:

-

Fourth Ecumenical Council (Chalcedon; East; 451 CE)—in canon 15, an earlier minimal age of sixty...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 7 photographs, 2 tables |

| Verlagsort | Westmont |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | ancient church history • Ancient Near East • Artemis • Bible • Biblical Studies • childless Christian • Ephesians • Ephesus • epistles • Gender equality • Greek Mythology • Infertility • New Testament • Pauline Studies • women in ministry |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0593-X / 151400593X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0593-4 / 9781514005934 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich