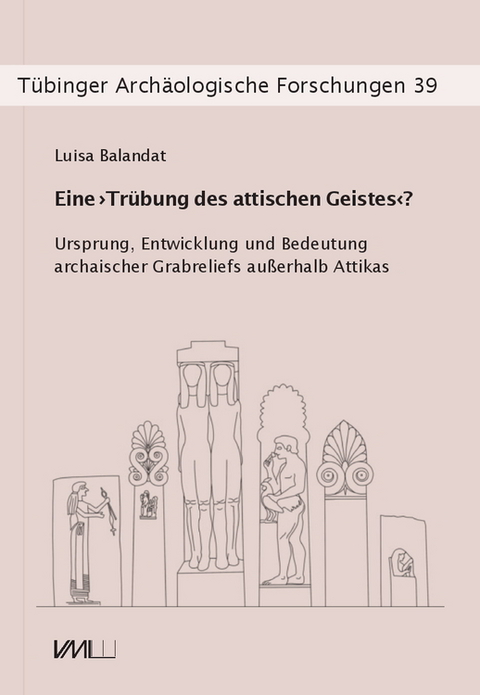

Eine ›Trübung des attischen Geistes‹?

Ursprung, Entwicklung und Bedeutung archaischer Grabreliefs außerhalb Attikas

Seiten

2023

|

1., Aufl.

VML Vlg Marie Leidorf (Verlag)

978-3-89646-870-3 (ISBN)

VML Vlg Marie Leidorf (Verlag)

978-3-89646-870-3 (ISBN)

Die Sammlung und Interpretation antiker Grabreliefs aus Attika kann bereits auf eine mehr als einhundertjährige Forschungsgeschichte zurückblicken. Für die archaische Zeit bleibt G. M. A. Richters Zusammenstellung das Standardwerk, obwohl sich unsere Kenntnis der Epoche deutlich vergrößert hat. Die figuralen Grabstelen aus dem übrigen griechischen Raum wurden bisher meist aus einem ›attischen Blickwinkel‹, als bloße Rezipienten des Vorbilds Athen erklärt. Eine Zusammenstellung und Analyse der außerattischen Stücke stellt die Anwendbarkeit eines solchen Zentrum-Peripherie-Modells auf die Gesamtheit archaisch-griechischer Grabreliefs infrage. Aus ihr geht beispielsweise hervor, dass die Sitte der Darstellung des Toten auf seinem Grabstein nicht in Athen, sondern auf Kreta und den Kykladen am weitesten zurückreicht und wahrscheinlich durch andere, nichtgriechische Einflüsse angeregt wurde. Anders als im Falle der Rundplastik lassen sich mögliche Vorbilder hier weniger in Ägypten als vielmehr im syro-hethitischen Raum finden. Dabei fällt auf, dass die jeweils frühesten figuralen Grabstelen in den unterschiedlichen griechischen Regionen zwar zeitnah zueinander, nämlich im späteren 7. und frühen 6. Jh. v.Chr., aber unabhängig voneinander entstehen. In einer zweiten Phase, etwa im ersten und zweiten Drittel des 6. Jh., werden die frühesten figuralen Grabmäler innerhalb der Regionen weiterentwickelt; es entstehen ›Lokaltraditionen‹, deren Existenz man bislang bestritten hat. Erst in einer dritten Phase, in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 6. und zu Beginn des 5. Jh., lösen sich diese Lokaltraditionen unter der Zunahme attischen Einflusses auf; das Zentrum-Peripherie-Modell ist demnach ausschließlich auf die Phase des Übergangs von der archaischen zur klassischen Epoche anwendbar. Über die Grenzen des griechischen Raumes haben dagegen offenbar weder die attischen noch die außerattischen Grabreliefs archaischer Zeit ausgestrahlt, wie Exkurse zu den sogenannten karisch-ägyptischen Stelen sowie zu Grabdenkmälern aus dem italischen Raum verdeutlichen. So lässt eine uneingeschränkte Sichtweise auf die griechische und die jenseits ihrer Grenzen liegende Sepulkralkunst sowohl die Existenz starker Regionalismen als auch die Mobilität von Ideen in archaischer Zeit zutage treten und bereichert unser Bild von dieser Epoche.

The collection and interpretation of ancient funerary reliefs from Attica can look back on more than a century of research history. For the Archaic period, G.M.A. Richter’s compilation remains the standard work, although our knowledge of the period has expanded considerably. So far, the figurative funerary stelae from the remainder of the Greek area have been explained from an “Attic point of view”, as simple recipients of examples set in Athens. The present compilation and analysis of the pieces from outside Attica challenges the usefulness of such a centre-periphery model for interpreting Archaic-Greek funerary reliefs as a whole. For example, it is shown that the custom of depicting the deceased on their tombs has its longest pedigree in Crete and the Cyclades, rather than Athens, and was probably inspired by other, non-Greek influences. In contrast to sculpture, possible sources here are found not so much in Egypt, but rather in the Syrian-Hittite area. Notably, the respectively earliest funerary stelae in the different Greek regions appear chronologically close to each other, in the later 7th and early 6th centuries B.C., but independently of each other. In a second phase, spanning roughly the first and second thirds of the 6th century, the earliest figurative funerary monuments in each region are developed further and “local traditions” emerge, whose existence has so far been denied. It is only in a third phase, in the final decades of the 6th and the early 5th centuries, that these local traditions dissolve under the influence of Attica; the centre-periphery model is therefore only applicable to the transitional phase between the Archaic and Classical periods. In contrast, beyond the limits of the Greek areas, neither Attic nor non-Attic Archaic funerary reliefs appear to have had any influence, as illustrated by asides on the so-called Carian-Egyptian stelae and on funerary monuments from the Italic region. In this way, an unrestricted view on sepulchral art in Greece and beyond its borders reveals both the existence of strong regional patterning and the mobility of ideas in Archaic times, thus enriching our view of this period. The collection and interpretation of ancient funerary reliefs from Attica can look back on more than a century of research history. For the Archaic period, G.M.A. Richter’s compilation remains the standard work, although our knowledge of the period has expanded considerably. So far, the figurative funerary stelae from the remainder of the Greek area have been explained from an “Attic point of view”, as simple recipients of examples set in Athens. The present compilation and analysis of the pieces from outside Attica challenges the usefulness of such a centre-periphery model for interpreting Archaic-Greek funerary reliefs as a whole. For example, it is shown that the custom of depicting the deceased on their tombs has its longest pedigree in Crete and the Cyclades, rather than Athens, and was probably inspired by other, non-Greek influences. In contrast to sculpture, possible sources here are found not so much in Egypt, but rather in the Syrian-Hittite area. Notably, the respectively earliest funerary stelae in the different Greek regions appear chronologically close to each other, in the later 7th and early 6th centuries B.C., but independently of each other. In a second phase, spanning roughly the first and second thirds of the 6th century, the earliest figurative funerary monuments in each region are developed further and “local traditions” emerge, whose existence has so far been denied. It is only in a third phase, in the final decades of the 6th and the early 5th centuries, that these local traditions dissolve under the influence of Attica; the centre-periphery model is therefore only applicable to the transitional phase between the Archaic and Classical periods. In contrast, beyond the limits of the Greek areas, neither Attic nor non-Attic Archaic funerary reliefs appear to have had any influence, as illustrated by asides on the so-called Carian-Egyptian stelae and on funerary monuments from the Italic region. In this way, an unrestricted view on sepulchral art in Greece and beyond its borders reveals both the existence of strong regional patterning and the mobility of ideas in Archaic times, thus enriching our view of this period.

The collection and interpretation of ancient funerary reliefs from Attica can look back on more than a century of research history. For the Archaic period, G.M.A. Richter’s compilation remains the standard work, although our knowledge of the period has expanded considerably. So far, the figurative funerary stelae from the remainder of the Greek area have been explained from an “Attic point of view”, as simple recipients of examples set in Athens. The present compilation and analysis of the pieces from outside Attica challenges the usefulness of such a centre-periphery model for interpreting Archaic-Greek funerary reliefs as a whole. For example, it is shown that the custom of depicting the deceased on their tombs has its longest pedigree in Crete and the Cyclades, rather than Athens, and was probably inspired by other, non-Greek influences. In contrast to sculpture, possible sources here are found not so much in Egypt, but rather in the Syrian-Hittite area. Notably, the respectively earliest funerary stelae in the different Greek regions appear chronologically close to each other, in the later 7th and early 6th centuries B.C., but independently of each other. In a second phase, spanning roughly the first and second thirds of the 6th century, the earliest figurative funerary monuments in each region are developed further and “local traditions” emerge, whose existence has so far been denied. It is only in a third phase, in the final decades of the 6th and the early 5th centuries, that these local traditions dissolve under the influence of Attica; the centre-periphery model is therefore only applicable to the transitional phase between the Archaic and Classical periods. In contrast, beyond the limits of the Greek areas, neither Attic nor non-Attic Archaic funerary reliefs appear to have had any influence, as illustrated by asides on the so-called Carian-Egyptian stelae and on funerary monuments from the Italic region. In this way, an unrestricted view on sepulchral art in Greece and beyond its borders reveals both the existence of strong regional patterning and the mobility of ideas in Archaic times, thus enriching our view of this period. The collection and interpretation of ancient funerary reliefs from Attica can look back on more than a century of research history. For the Archaic period, G.M.A. Richter’s compilation remains the standard work, although our knowledge of the period has expanded considerably. So far, the figurative funerary stelae from the remainder of the Greek area have been explained from an “Attic point of view”, as simple recipients of examples set in Athens. The present compilation and analysis of the pieces from outside Attica challenges the usefulness of such a centre-periphery model for interpreting Archaic-Greek funerary reliefs as a whole. For example, it is shown that the custom of depicting the deceased on their tombs has its longest pedigree in Crete and the Cyclades, rather than Athens, and was probably inspired by other, non-Greek influences. In contrast to sculpture, possible sources here are found not so much in Egypt, but rather in the Syrian-Hittite area. Notably, the respectively earliest funerary stelae in the different Greek regions appear chronologically close to each other, in the later 7th and early 6th centuries B.C., but independently of each other. In a second phase, spanning roughly the first and second thirds of the 6th century, the earliest figurative funerary monuments in each region are developed further and “local traditions” emerge, whose existence has so far been denied. It is only in a third phase, in the final decades of the 6th and the early 5th centuries, that these local traditions dissolve under the influence of Attica; the centre-periphery model is therefore only applicable to the transitional phase between the Archaic and Classical periods. In contrast, beyond the limits of the Greek areas, neither Attic nor non-Attic Archaic funerary reliefs appear to have had any influence, as illustrated by asides on the so-called Carian-Egyptian stelae and on funerary monuments from the Italic region. In this way, an unrestricted view on sepulchral art in Greece and beyond its borders reveals both the existence of strong regional patterning and the mobility of ideas in Archaic times, thus enriching our view of this period.

| Erscheinungsdatum | 26.07.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Tübinger Archäologische Forschungen ; 39 |

| Verlagsort | Rahden |

| Sprache | deutsch |

| Maße | 210 x 297 mm |

| Gewicht | 1610 g |

| Einbandart | gebunden |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike |

| Schlagworte | Archaik • Grabrelief • Griechenland • Ikonographie • Ikonologie • Skulptur |

| ISBN-10 | 3-89646-870-7 / 3896468707 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-89646-870-3 / 9783896468703 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Mehr entdecken

aus dem Bereich

aus dem Bereich

die Inszenierung der Politik in der römischen Republik

Buch | Hardcover (2023)

C.H.Beck (Verlag)

48,00 €

Buch | Hardcover (2024)

Klett-Cotta (Verlag)

50,00 €