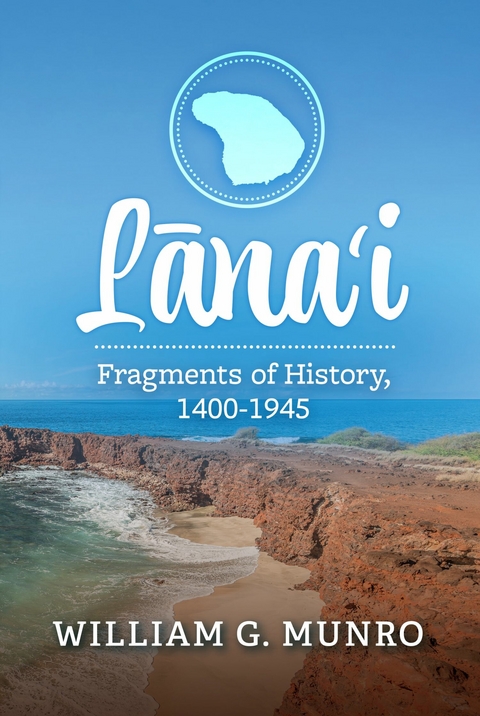

Lana'i (eBook)

274 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-6873-8 (ISBN)

Throughout his life, Munro remained a student of Lana'i's history. In his own words, "e;the motivation for this account is humdrum - the curiosity of one who spent his childhood on Lana'i. At the time, there were few historical works about the island in general circulation. His family had copies of Kenneth Emory's study of LA na'i and Harold Stearns' work on the geology and groundwater resources. Anecdotes told at the dinner table and chance contacts with old-timers were about the only other sources. People reared on LA na'i almost always have a fondness for, and even pride in, the place. Thus, the lack of sources of historical information can be a source of frustration."e;Upon retirement and accompanied by his wife Jean, he began this book as a compilation of his findings, supplemented by a wealth of photographs and images. The book goes into considerable detail on ownership history, the variety and challenges of early settlement, and the economic development of the island up through 1945.

Chapter 1.

Early Settlement

The first Polynesian voyagers who arrived in the Hawaiian Islands, probably around 450 AD, had won a life-or-death gamble. One or more chiefs, their families and their followers had decided to leave their homes in the Marquesas or Society Islands. They might have lost a war, suffered from overcrowding or other social problems or possibly were bored and adventurous1. Their objective was to find a new island home far to the north in the unknown ocean. They may not have been the first group to try this, and they may have constituted the few survivors of a much larger group.

This relatively small band came upon an uninhabited island group with climate, topography, water resources and fisheries not greatly different from their former home thousands of miles away on the other side of the equator. Likely they arrived with little left in their supplies, having consumed everything edible on their canoes. The Hawaiian environment was filled with plants, insects and birds, but few of the food plants or terrestrial animals were those with which they were familiar. Initially, they had to learn to survive, for the most part, on what they found on their arrival. They also brought on their journey some of the edible plants known to them, including the fruit of the pandanus tree, the roots of the tī plant (Cordyline terminalis), taro and sweet potatoes. The early settlers discovered that the pith of tree ferns could be eaten, as well as the small fruit of other endemic species. There was also plenty of fish, limu (seaweed) and shellfish, but for some time, little or no taro, sweet potatoes, pigs, dogs or chickens were available, as the new stock needed to be developed. It is likely that early life in the Hawaiian Islands was filled with challenges.

The pioneers brought with them a tribal social organization similar to those found in Samoa and New Zealand — one that was founded on a familial relationship with ‘āina (land). The original settlements were located near the mouths of well-watered valleys where access to coastal fisheries was easy. As the population increased over time, the settlers gradually spread to all the main islands. They existed in complete isolation from the rest of the world.

Hundreds of years later, probably about 1100 AD, an especially adventurous sailing party from Kahiki (the ancestral homeland) rediscovered the Hawaiian Islands on a long voyage of exploration. It is likely that a good many other exploring parties had tried to come this way over the centuries but had perished at sea. The party who had survived the journey had brought with them seeds and seedlings of staple food plants and other needed trees and shrubs, and a few dogs, pigs and chickens, in addition to provisions for an extended voyage. With these supplies and the favorable environment, they found that they could prosper in the new islands.

The return to Kahiki

Not too long after their arrival and establishment in Hawai‘i, it was decided that Pā‘ao, one of their chief priests, and his navigator and canoe crew would return to Kahiki to recruit more chiefs and their followers to come to the new islands to help populate them. He was also to bring back a new supply of breadfruit seedlings, as the original supply had not survived the voyage. The navigators on the original northbound voyage had carefully observed the stars of the northern hemisphere, which were new to them. They deepened their relationships with the stars they knew and with the winds and calms of the equatorial region as they crossed it. Coupled with this knowledge and the estimated distances they had traveled on various courses, Pā‘ao’s navigator probably had little trouble finding their way back to Tahiti (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rand McNally & Co. Atlas of the World, Map of Oceania and Malaysia (1892) View Including the Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands and Larger Polynesian Island Group (Digital Collection, Archive.org)

Word of their discovery spread, and soon a small group of chiefs, with their families, navigators and retainers, loaded up their voyaging double canoes and headed north. With Pā‘ao’s description of the resources at their destination and a pretty good idea of the probable length of the voyage, they were able to carry with them a wide selection of goods and supplies — including breadfruit — which was originally nonexistent in Hawai‘i, as well as other provisions for the trip.

Early settlement occurred on the larger islands where fresh water sources and sheltered bays could be easily accessed (Cordy, 2000). The second wave of island settlers did come into conflict with the original settlers, however, and native lore indicates the original settlers drove them out, first to remote places on Kaua‘i and then out of the main Hawaiian Islands entirely. It is suggested that the remnants of these unlucky people fled northwest to Neckar and Nīhoa Islands toward Midway. These are not habitable islands. After leaving evidence of their occupation on these barren rocks in the form of stone terraces and other signs of extended sojourns, they headed out to sea once more and disappeared forever. The Tahitian Hawaiians explained in legends that the many existing stonework improvements left behind by their predecessors were the work of a race of small-statured people who lived in the mountains in some invisible fashion. These legends indicated that these “Menehunes2” would come out at night and accomplish a project of any size and complexity in a single night. They were reputed to come down out of the mountains and complete some overnight endeavor to assist a mortal Hawaiian but only rarely and under special circumstances.

Cultivating land

After the dispossession and elimination of the earlier settlers, there was essentially a peaceful period for the new Hawaiians. There was no real competition for resources. When one valley became too heavily populated, some of its inhabitants could move to a new valley. As in the Tahitian, Samoan and Maori societies, cultivated land was controlled collectively by the cultivators or sometimes extended families or perhaps tribal groups who could pass on this control to their descendants, under tribal custom.

This custom was likely the result of the need for cultivators to invest a great deal of long-term effort in developing irrigation systems and flooded terraces for taro, planting and caring for breadfruit, banana, pandanus, paper mulberry and other essential trees and building house foundations, stone fences and livestock pens.

Up to about 1275 AD, periodic canoe voyages to and from the “old country” of Tahiti took place, some bringing new influxes of settlers to Hawai‘i. But then all communication between Hawai‘i and Tahiti ceased, and the Hawaiian culture, customs and even language began to diverge from those of Tahiti. It is hard to guess the reason for this deliberate isolation. Surely the voyaging skills and knowledge still existed when voyaging ceased. Perhaps there was simply no need to travel to Tahiti any more. The Hawaiian population needed no more recruits from Tahiti, and everything that one place possessed was also available in the other. Over time, the voyaging traditions and skills in both places disappeared, leaving the Micronesians the sole Pacific practitioners.

People began to settle in less desirable places on the major islands and in the wetter sections of Moloka‘i, as the overall population expanded. There were probably transient fishermen and other temporary groups gathering wild plants and building materials on Ni‘ihau, Kaho‘olawe and Lāna‘i, but the general lack of well-watered sites on these islands would have discouraged large permanent settlement as long as better sites on other islands were still available.

Hierarchies of a feudal society

The relatively peaceful period ended in the thirteenth century when the important chiefs began to wage war with one another to aggrandize their power and increase their control over land and other resources. This development was probably the result of having all the desirable land occupied and in use, with the population still steadily rising. Between then and the arrival of the first foreigners, a full-fledged feudal society developed. There were the two customary classes of people characteristic of feudal societies. There was a hierarchy of chiefs of various ranks and their families, known as the ali‘i, and a class of commoners (maka‘āinana) making up the rest of the population. Aggressive chiefs, through war, negotiation and intimidation, gained control over larger and larger areas.

Other lower-ranking or defeated chiefs had to ally themselves and their commoner followers with dominant chiefs to avoid dispossession or annihilation. A standard practice at that time was for a chief who had won a war to take control of the lands of the defeated chief and redistribute them to his subordinate chiefs as he saw fit. By the fifteenth century, the feudal process had developed to the point where each of the major islands (Hawai‘i, Maui, O‘ahu and Kaua‘i) was controlled by the most powerful chief, who was the mō‘ī, or king, sometimes sharing power in large districts with another chief. When these island kings assumed power, they assigned land to their highest-ranking subordinate chiefs who could, and often did, reassign parts of their holdings to konohiki (chiefs, landlords or chiefs’ representative). As in all other feudal societies, the land-controlling chiefs owed the higher-ranking...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.12.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-6873-X / 166786873X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-6873-8 / 9781667868738 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 25,2 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich