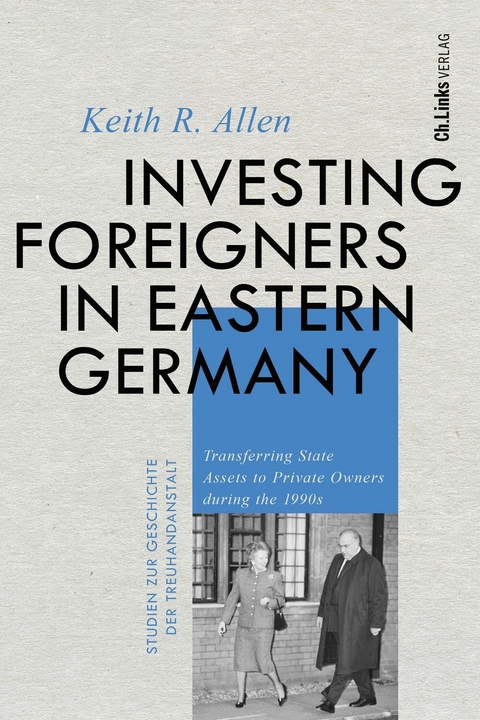

Investing Foreigners in Eastern Germany (eBook)

432 Seiten

Aufbau digital (Verlag)

978-3-8412-3214-4 (ISBN)

Internationale Investoren in Ostdeutschland

Die rapide Massenprivatisierung der ostdeutschen Wirtschaft nach der 'Wende' ging zu keinem Zeitpunkt allein von der alten Bundesrepublik aus. Keith R. Allen schildert in seiner englischsprachigen Studie das Engagement von Akteuren aus dem Ausland - vor allem aus Westeuropa - als Investoren, als Rat- und Kapitalgeber sowie als Mitentscheider über erhebliche Beihilfen von Land und Bund. Es geht nicht darum zu bewerten, was bei der Übernahme der ostdeutschen Wirtschaft durch die Bundesrepublik falsch - oder möglicherweise richtig - gelaufen ist. Vielmehr zeigt diese Studie, dass die Marktentwicklungen im Deutschland der 1990er Jahre eng mit Akteuren, Ereignissen und Interessen in westeuropäischen Ländern und den USA verknüpft waren.

Ein englischsprachiger Beitrag zur Geschichte der Treuhandanstalt

Keith R. Allen ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Historischen Institut der Universität Leipzig. Zu seinen beruflichen Stationen gehörten die schweizerische Bergier-Kommission, das US Holocaust Memorial Museum und das Leibniz-Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin. 2013 erschien von ihm im Ch. Links Verlag 'Befragung - Überprüfung - Kontrolle. Die Aufnahme von DDR-Flüchtlingen in West-Berlin bis 1961'.

1. Swiss Mediators in Eastern Germany after (and before) 1989

This chapter explores how a specific constellation of Swiss consulting experts, financial advisors, and diplomats became involved in the economic restructuring of eastern Germany after November 1989. A nation of fewer than seven million, the Swiss topped the list of Treuhandanstalt (Treuhand) investors in the five states of eastern Germany and the eastern half of Berlin, surpassing the efforts of much larger and more influential competitors, including the enlarged Germany’s most important European Community (EC) partners, Britain and France (I address these two countries’ engagements in eastern Germany in Chapter 3). During the Treuhand era, Switzerland led the nations investing in eastern Germany, with 139 privatizations, followed by Britain (124), Austria (100), and the Netherlands (96).

Ties between East and West Germany help to explain how Switzerland became an important investor in the new federal states. Even more significant in accounting for Swiss successes were features of Switzerland’s own economy. The origins of Swiss engagements ultimately lay primarily in developments in Bern, Basel, and especially Zurich, and only secondarily in unifying Germany. A rapid post-Wall deepening of Swiss contacts with authorities of the German Democratic Republic helped pave the way for the involvement of Swiss consulting experts, financial professionals, and diplomats in the economic restructuring of eastern Germany as its economy simultaneously opened up and drastically contracted after November 1989. Chapter 1 illustrates that capital did not merely “flow” across unifying Germany’s borders, as many economists’ definitions of direct sales to foreigners suggest. When it came to the sale of assets to investors from Switzerland and other nations, historical relationships figured in significant ways that economic theory often neglects to consider.1 Facilitators within and beyond Germany actively promoted (and thwarted) investments. Well-placed individuals cashed in on ties forged in the 1980s with high-ranking East Germans. Nor was investment between firms—typically described by economists as private or external investment—decoupled from public debt.2 Rooted in commercial relationships between the two Germanys in the decade prior to the Treuhand-led privatization, Swiss approaches represent the obverse of Anglo-American-inspired consultancy models that granted limited attention to specific investment contexts.

Swiss investment successes flowed from many cultural similarities and a few key differences. The Alpine federation and West Germany shared much, notably a language (for two-thirds of Swiss citizens), a border, legal norms, and extensive economic and social contacts, including with the former East Germany.3 Even apparent imbalances in the relationship, such as the fact that the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) was Switzerland’s most important trading partner and not vice versa and that Switzerland’s banks were far more successful than those in West Germany in securing the wealth of private individuals from around the world, point more to shared than to divergent interests.4

Then as now, the importance of German economic ties for Swiss authorities can hardly be overstated. For all the similarities with West Germany’s economy, notably its own niche manufacturing enterprises like those typifying the Federal Republic’s Mittelstand, Switzerland differed from its powerful northern neighbor in significant ways. Prominent among these were its banking secrecy laws and its numerous “asset managers,” affiliates, brokerages, investment houses, consulting concerns, and private banks. Having played special roles in facilitating commerce between the postwar German states during the eras of détente, these actors’ engagement informed Swiss approaches immediately after the Wall fell.

A striking aspect of post-Wall economic developments in East and West Germany is the mediation of German-speaking investment promoters based in Switzerland. This chapter traces mediated Swiss engagements within eastern and western Germany in order to lay bare economic interactions among several Central European nations after November 9, 1989. Swiss intermediaries moved swiftly to exploit changing relations between industrial and political leaders of the two German states. The most important organization was a Swiss-German trade association known as the Handelskammer Deutschland-Schweiz (hereafter referred to as the Handelskammer). The Handelskammer faced internal competition within Switzerland, a fact that that strengthened the Alpine country’s initiatives to exploit rapidly changing relations between the two postwar German states vis-à-vis other European—and especially western German—competitors after November 9, 1989.

Inner-German Ties and Swiss Mediation

In Switzerland, rivalry within the small world of business associations animated the scramble to define investment opportunities in East Germany. The list of intermediaries extended from the Handelskammer to a less prominent association known as the Vereinigung Schweizerischer Unternehmer in Deutschland (Association of Swiss Companies in Germany, hereafter Vereinigung) based in Basel. It also included today-forgotten associations, including a German-Swiss organization named Innovatio.

Representatives of the Fribourg-based Innovatio, not the Handelskammer or the Vereinigung, arranged the first high-level East German visit to the Federal Republic after the dramatic opening of the border in divided Berlin. During the first week after November 9, 1989, Albert Jugel—the former general director of a well-known state-owned industrial conglomerate (Kombinate) in East Germany, the data processing and office equipment manufacturer Robotron—traveled to West Germany’s capital of Bonn, as well as to the West German cities of Cologne, Dortmund, Frankfurt am Main, Hanover, Kronberg, and Munich. Jugel did so at the behest of reform-minded socialist leaders in East Germany. These included Wolfgang Berghofer, the mayor of Dresden, and Hans Modrow, the last socialist East German minister president.

Behind-the-scenes Swiss intermediation, coupled with long-standing ties between the two German states, ensured that Jugel, at that time a professor of automation technology at the Technical University in Dresden, was able to meet with influential figures in West German finance, industry, and politics. Reimut Jochimsen, the economics minister of West Germany’s largest state government, North Rhine–Westphalia, and Dieter von Würzen, an influential state secretary in the Federal Ministry of Economics, were among the long list of notables to meet Jugel.5 The East German also exchanged views with Detlev Rohwedder, director of steel giant Hoesch and, from September 1, 1990 to April 1, 1991, president of the Treuhand. Rohwedder used Jugel’s visit to explore how East German companies could be enlisted to produce steel products for West Germany’s automobile industry. To this end, the Dortmund steel chief shared with Jugel his plans to meet Robotron’s general director Friedrich Wokurta, Jugel’s successor, and Berghofer, on December 18, 1989.6

Business in the weeks and months immediately after November 1989 was often grounded in socialist-era trade activities that united profit seekers from East and West Germany. In early January 1990, at least 140 West German companies were already involved in some 1,100 industrial cooperation projects across socialist East Germany.7 Rohwedder’s ties to German Democratic Republic (GDR) authorities, like those of an impressive variety of West German industrialists and ministerial officials, were not new. First as a state secretary in the Federal Ministry of Economics and then as Hoesch’s director, Rohwedder had immersed himself in trade deals with East German authorities for two decades: one of the largest was Hoesch’s extensive cooperation with the EKO Stahl works in Eisenhüttenstadt on East Germany’s border with Poland.8 According to an estimate compiled by Rohwedder’s deputy at...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.4.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Studien zur Geschichte der Treuhandanstalt |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Beruf / Finanzen / Recht / Wirtschaft ► Wirtschaft |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Wirtschaft ► Volkswirtschaftslehre | |

| Schlagworte | Advisors • Capital Providers • co-decision-makers • Eastern Germany • Europäische Union • European Union • Investoren • investors • Marktwirtschaft • Massenprivatisierung • Planwirtschaft • Privatisierung • Privatization • Reunification • Socialist economy • Transformation • Treuhand • United States |

| ISBN-10 | 3-8412-3214-0 / 3841232140 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-8412-3214-4 / 9783841232144 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 793 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich