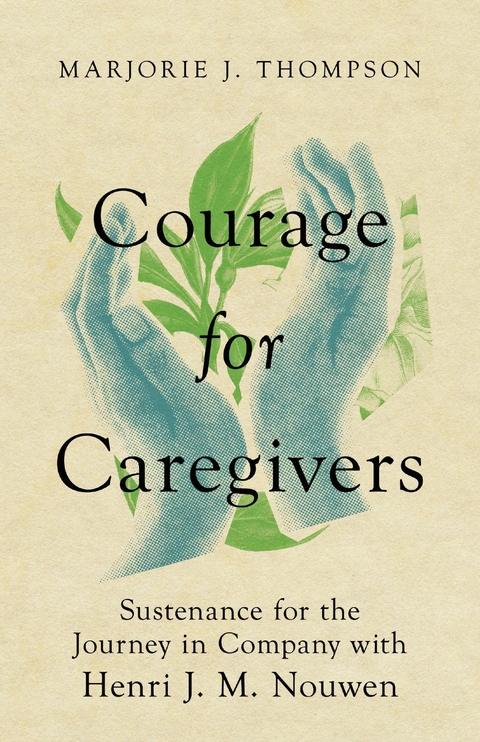

Courage for Caregivers (eBook)

168 Seiten

IVP Formatio (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0557-6 (ISBN)

Marjorie J. Thompson is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church USA. She has served as a teacher, writer, and retreat leader for more than thirty years. Henri J. M. Nouwen was one of her early spiritual mentors and personal friend of her husband, John Mogabgab, who served as Henri's teaching and research assistant for five years at Yale Divinity School.

Marjorie J. Thompson is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church USA. She has served as a teacher, writer, and retreat leader for more than thirty years. Henri J. M. Nouwen was one of her early spiritual mentors and personal friend of her husband, John Mogabgab, who served as Henri's teaching and research assistant for five years at Yale Divinity School.

HENRI BROUGHT PARTICULAR insights to our experience of caring for each other. We can identify three keys to explore:

-

1. Care is not cure: true care allows us to be comfortable with weakness.

-

2. Care expresses and expands our compassion, understood as suffering with others.

-

3. Care draws us into profound mutuality, both in shared vulnerability and shared gifts.

HENRI’S WISDOM ON CARE VERSUS CURE

A helpful starting point is Henri’s insistence that “care is distinctly different from cure.”1Henri believed that our care for the elderly helps to reveal this truth with singular clarity, because more than other age groups “the elderly confront us all with the fact that the concept of a final cure is an illusion.”2In a culture fixated on problem solving, we are often more interested in cure than care. Care professionals like doctors, psychologists, and social workers are trained to evaluate their competence by standard measures of successful treatment. Yet, Henri notes, “our altruistic intention to cure the ills of others has oriented us toward success in the eyes of others.”3Success tends to build a sense of power and prestige in those who can cure. While we are surely happy for effective treatment, the drive to cure may not always result in true care. “Many people have returned from a clinic cured but depersonalized” by aloof or arrogant professionals. It is a real but often unconscious temptation for care professionals to relate to their patients “as the powerful to the powerless, the knower to the ignorant.”4

In contrast to cure, Henri lifts up the beauty and value of authentic care:

What is care? The word finds its origin in the word kara, which means to lament, to mourn, to participate in suffering, to share in pain. To care is to cry out with those who are ill, confused, lonely, isolated, and forgotten, and to recognize their pains in our own heart. To care is to enter into the world of those who are broken and powerless and to establish there a fellowship of the weak. To care is to be present to those who suffer, and to stay present, even when nothing can be done to change their situation.5

Care is the context within which cure, where possible, may be received as gift. Yet, Henri assures us, when we cannot cure we can still care. It is always possible to say—through our presence, listening, words, or gestures—“I see your pain. I cannot take it away, but I won’t leave you alone.”6

For too long care has been conceived of as either practitioner-centered or patient-centered. In actuality, the healing relationship has always been a crucible for mutual transformation.

—SAKI SANTORELLI

SUFFERING AND COMPASSION

Henri helps us to embrace care for others as a way of participating in their suffering. Those of us with long experience in caregiving for family members will know two sides to this suffering: the difficulty, weakness, and pain of those who receive our care; and our struggle as caregivers to balance family expectations, work responsibilities, time constraints, limited energy, and perhaps sporadic efforts at self-care. There are seasons when we feel we are barely staying afloat on a sea of swirling changes and swelling demands.

Since suffering is a reality on both sides of the care relationship, one constructive thing we can do is to ask ourselves long-term questions like these:

-

• How do I choose to face pain or distress with courage, hope, even curiosity?

-

• How might I not only endure but embrace these circumstances?

-

• What can I learn, here and now, that serves my growth in love?

As we engage our suffering and the suffering of others with courage, we discover growing compassion. Henri’s friend Parker Palmer likes to say that there are two ways a heart can break: It can be shattered into a thousand shards that explode and implode to wound others and oneself; or it can break open to receive more reality, insight, and love. A heart that breaks open under the pressure of suffering becomes more compassionate. Henri once wrote, “My true call is to look the suffering Jesus in the eyes and not be crushed by his pain, but to receive it in my heart and let it bear the fruit of compassion.7

The term compassion is rooted in the Latin pati (to bear or suffer) and cum (with). Compassion means “to bear with” or “suffer with.” It is closely connected with empathy which shares the Latin root pati, and signifies an ability to feel with the other. Yet while there is a strong impulse in our heart to feel with others, there is an equally powerful resistance to feeling too much! As Henri points out,

Compassion is hard because it requires the inner disposition to go with others to the place where they are weak, vulnerable . . . and broken. But this is not our spontaneous response to suffering. What we desire most is to do away with suffering by fleeing from it or finding a quick cure for it.8

How many are the ways we recoil from physical and mental anguish! Suffering is a universal human experience from which no one escapes in this world. Yet no human experience raises so many profound and painful questions about the meaning and purpose of our earthly lives. Although we may ask such questions of people we hope are wiser than we, the real audience for our deepest questions is always God. Anguished questioning of God in relation to suffering is age-old, and never fully resolved by reason.

When we suffer greatly, painful questions fly from our hearts like flaming arrows: Why is this happening? What have I done to deserve this? Is God angry with me? Why doesn’t God heal me? Will God ever answer my prayers? We ask similar questions on behalf of those we love, especially when their suffering is hard to bear.

The question, “Why?” spontaneously emerges. “Why me?” “Why now?” “Why here?” It is so arduous to live without an answer to this “Why?”

—HENRI NOUWEN

Behind our questions lie the eruption of difficult feelings: physical, mental, and emotional hurt; a deep sense of unfairness and consequent anger; sorrow and grief over loss; numbness and incomprehension; fear and uncertainty; helplessness and despair. Henri was deeply acquainted with these hard feelings. By example he encouraged us to be honest and realistic about them. As we explore the challenges of caregiving, we will look at stories that help us acknowledge and name our strong feelings of pain, fear, frustration, and exhaustion.

Yet Henri also keenly understood how faith sustains and strengthens us in our suffering. He assures us that before it is anything else, the mystery of salvation is this: God came to us in Jesus not to take our pains away but to share them with us. Through his passion he cried out alongside us in our agonies, our incomprehension, our loneliness and felt abandonment. He entered so fully into the human experience, and drank so deeply the bitter cup of our misery, that nothing of human suffering is now alien to God. All our suffering is held in God’s heart and embraced by divine love.

There can be no human beings who are completely alone in their sufferings since God, in and through Jesus, has become Emmanuel, God with us. It belongs to the center of our faith that God is a faithful God, a God who did not want us to ever be alone, but who wanted to understand—and stand under—all that is human. The Good News of the Gospel, therefore, is not that God wanted to take our suffering away, but that God became part of it.

—HENRI NOUWEN

Jesus comes into human life revealing God’s humility (Philippians 2:5–8). In Jesus, God stoops to become small and weak with us in a manger birth. In Jesus, God welcomes the neglected, the feared, the despised, and the broken in a mission of compassionate transformation. In Jesus, God takes on our suffering and death in complete solidarity. Beyond his earthly life, Jesus invites us to share symbolically in his suffering every time we “eat this bread and drink this cup,” remembering his death and resurrection. Henri speaks of this cup:

Jesus’ cup is the cup of sorrow, not just his own sorrow but the sorrow of the whole human race. It is a cup full of physical, mental, and spiritual anguish. . . . It is the cup full of bitterness. Who wants to drink it?. . . Too much pain to hold, too much suffering to embrace, too much agony to live through. Why, then, could he still say yes? . . . beyond all the abandonment experienced in body and mind Jesus still had a spiritual bond with the one he called Abba. He possessed a trust beyond betrayal, a surrender beyond despair, a love beyond all fears.9

Jesus never promises that we will escape our own suffering, but rather invites us to take up our cross and follow him. He asks if we can drink the cup he drinks, knowing we can only do so the same way he did—as “a deep spiritual yes to Abba, the lover of his wounded heart.”10 He assures us that he will be with us in our struggle to say yes—with us to the end of the age (Matthew 28:20), and even beyond what we perceive as the end of life: “I go to prepare a place for you. And . . . I will come again and take you to myself” (John 14:2–3). Jesus’ suffering was not the final word, and neither is ours. “Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.8.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | Au Pair • Babysitting • caregiver • Caregiving • caregiving parent • caretaker • chronic illness • compassion fatigue • Disability • Elder care • elderly family • elderly parent • End of Life • Father • Healthcare • Hospice • mother • Nanny • Nurse • stay at home mom • stay at home parent |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0557-3 / 1514005573 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0557-6 / 9781514005576 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich