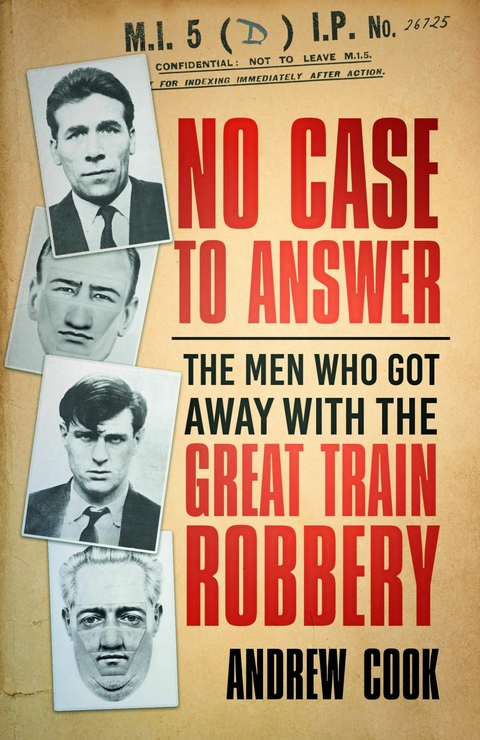

No Case to Answer (eBook)

372 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-070-5 (ISBN)

ANDREW COOK is an author and TV consultant with a degree in History & Ancient History. He was a programme director of the Hansard Scholars Programme for the University of London. Andrew has written for The Times, Guardian, Independent, BBC History Magazine and History Today. His previous books include On His Majesty's Secret Service (Tempus, 2002); Ace of Spies (Tempus, 2003); M: MI5's First Spymaster (Tempus, 2006); The Great Train Robbery (The History Press, 2013); and 1963: That Was the Year That Was (The History Press, 2013).

Andrew Cook is an author and TV consultant. He has written for The Times, Guardian, Independent, BBC History Magazine and History Today. His previous books include On His Majesty's Secret Service (Tempus, 2002), Ace of Spies (Tempus, 2003), M: MI5's First Spymaster (Tempus, 2006), The Great Train Robbery (THP, 2013) and 1963: That Was the Year That Was (THP, 2013).

PREFACE

This book is based on several years of carefully documented research, studying over a thousand pages of new material. Much of the detail recorded here has never before seen the light of day, being from closed, redacted, unfiled or retained sources.

My earlier book, published in 2013, The Great Train Robbery: The Untold Story from the Closed Investigation Files, was essentially the story of the robbery itself. It was based, on the whole, on documents from investigation files that had been opened as a result of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. The book was later used as a source for two television documentaries on the robbery, and the 2013 two-part World Productions/BBC1 television movie The Great Train Robbery: A Robber’s Tale & A Copper’s Tale. It was a great privilege to work with scriptwriter Chris Chibnall, and to watch the stars of the film, Jim Broadbent, Luke Evans, Robert Glenister, James Fox, Paul Anderson, Martin Compston, and a whole host of other great actors, bring the story to life during filming.

This second book, however, is about something very different. It is not really about the robbery itself, although inevitably its thread runs throughout the book. Almost anyone who has ever heard of the Great Train Robbery knows the names of those who will forever be associated with it – Bruce Reynolds, Buster Edwards, Gordon Goody, Ronnie Biggs, and so forth. They are virtually household names today. However, from the moment I first read Colin McKenzie’s book The Most Wanted Man over forty years ago, I was intrigued more by the untold story of the robbers who had no need to go on the run, were not handed down thirty-year sentences, and did not live their lives out of suitcases, forever looking over their shoulders. This book is about how and why they remained at liberty, and why the Director of Public Prosecutions deemed in 1964 that they had ‘no case to answer’ as far as the British judicial system was concerned.

Neither this book, nor the previous one, could ever have been written without the advent of Freedom of Information legislation in this country, and other countries around the world, during the past two decades. That in itself has not been a panacea, for a whole host of new obstacles and barriers have sprung up to counter it during the same period of time.

The ball really started rolling when the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, William Waldegrave, announced on 25 June 1992 the first tentative steps on the long and rocky road that would eventually lead to the UK’s Freedom of Information Act: ‘I would like to invite serious historians to write to me … those who want to write serious historical works will know, probably better than we do, of blocks of papers that could be of help to them which we could consider releasing.’

The response from historians, serious and otherwise, came a close second to rivalling the sacks of mail addressed to Santa Claus received every Christmas in sorting offices up and down the country. Thankfully, unlike Santa’s mountain of mail, the Post Office had a Whitehall address to which Waldegrave’s missives could be delivered.

Very few of those who put pen to paper were to receive much more than a cursory letter of acknowledgement. Still fewer were to get the green light to embark on the process of submitting references, a curriculum vitae and a list of previous publications. I was one of the fortunate few. My initial request was in respect to the MI6 spy Sidney Reilly and his activities in Russia shortly after the 1917 Revolution. Having successfully navigated my way through the vetting process, I eventually received a letter setting out the conditions for granting me access to the files I had requested. Suffice to say that none of these were found by myself to be in the least bit unreasonable or objectionable, and I was more than happy to sign a declaration acknowledging my obligations under the Official Secrets Acts, an undertaking I have abided by to this day.

I was fortunate, over the following two decades, to have been granted further access to other closed files on a range of topics. During that time, the Freedom of Information Act was passed in 2000 and came into effect on 1 January 2005. The Act gave citizens the right to access information held by public authorities. The intention of the Act was to try to make government more transparent and to increase public confidence in political institutions. Some have argued, over the past fifteen years or so, that this has either failed to achieve its objective or, in some cases, has actually achieved the opposite.

The percentage of Freedom of Information requests granted in full has apparently fallen from 62 per cent in 2010 to 44 per cent in 2019. Requests flatly denied have grown from 21 per cent to 35 per cent in the same period. The Ministry of Justice, the Treasury, the Health Department and the Home Office all have high rates of rejecting FOIs. The department with the highest number of FOI rejections is the Cabinet Office, which declined 60 per cent of FOI requests in 2019. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the regulator for the Freedom of Information Act, has seen its funding fall by 41 per cent in real terms in a decade, while the number of FOI complaints have grown significantly.

According to Katherine Gunderson of the Campaign for Freedom of Information, ‘Authorities have learnt that they can breach FOI deadlines and even ignore the ICO’s interventions without repercussions.’ Jon Baines, an FOI expert at the law firm Mishcon de Reya, has highlighted a tactic known as ‘stonewalling’, which involves public bodies, who are required to respond to Freedom of Information Requests within twenty working days, simply ignoring the request. Without a formal refusal, requesters cannot appeal to the Information Commissioner.

While I have certainly experienced a number of tactics over recent years to avoid responding to FOI requests or to release information, it has to be said that in some instances, funding cuts in the public sector have led to diminishing staff numbers handling such requests. This, in the view of some, has led directly to more FOI requests being rejected out of hand on tenuous grounds. Because of lack of search time, some are resorting to this tactic purely out of practicality, rather than seeking to deliberately withhold information from the public. The fact that files are now closed for a minimum period of twenty years, under the 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act, and not thirty as before, has also dramatically upped the workload of those whose job it is to prepare files for release and consider FOI requests.

It could also be argued, however, that Freedom of Information access, or lack of access, has become a distraction in terms of locating critical source material from the past.

The National Archives has a major clue within its name. The National Archives are, generally speaking, a repository for national records, not local or regional ones. While the Metropolitan Police, for example, is theoretically a police force covering the Greater London area, it is, to all intents and purposes, an unofficial national force. Its detectives, in particular, have more often than not been called in to assist on cases the length and breadth of the country for over 150 years. The Great Train Robbery, a crime that occurred in rural Buckinghamshire, is but one case in point.

Being a national archive, the records of provincial forces involved in the Great Train Robbery investigation, such as Surrey, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, City of London and Sussex constabularies, for example, are not to be found at The National Archives. Instead, these ‘provincial forces’ are responsible for their own record keeping, archiving, storage and policy, as is Royal Mail, who hold the records of the world’s oldest criminal investigation department, the Post Office Investigation Branch.

When I first began researching intelligence records well over twenty years ago, I quickly realised that, as with all hierarchical bureaucratic organisations, intelligence departments such as MI5 and MI6 will periodically copy in other government departments, such as the Ministry of Defence, Home Office, Foreign Office, Board of Trade, etc., with documents, particularly if they have a shared interest or are undertaking an assignment from one of them. When, decades later, the departmental weeders are going through files prior to releasing them to The National Archives, they will occasionally miss the significance of a document emanating from an intelligence department, and sign off the entire file as ‘open’ for the purposes of public access. In this way, a copy document, the original of which will never see the light of day, will enter the public domain.

When researching the Royal Mail’s train robbery investigation files, I soon spotted a similar pattern, i.e. the Flying Squad would periodically supply the IB with investigation reports, and vice versa. The same picture emerged when I examined the records of some of the provincial police forces, particularly those in close proximity to London and/or the scene of the crime. They were receiving almost daily reports and telexes from Scotland Yard. Unlike the Metropolitan Police originals, which are mostly closed and inaccessible to the public, these provincial force copies are, on the whole, accessible to the discerning researcher.

Another researching ‘loophole’ that can sometimes be found is in the fact that while a file on a particular individual or event might be closed to the public in the UK, in another connected...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.4.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Politik / Gesellschaft | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Zeitgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1963 • Bob Welch • bruce reynolds • buckinghamshire • Buster Edwards • charlie wilson • Glasgow-Euston • Gordon Goody • great train robbery. train robber • great train robbery. train robber, tom wisbey, 1963, railway detective, bruce reynolds, ronnie biggs, Gordon Goody, Buster Edwards, Charlie Wilson, Roy James, John Daly, Jimmy White, Jim Hussey, Bob Welch, Roger Cordrey, mentmore bridge, buckinghamshire, Glasgow-Euston, sears crossing • Jim Hussey • Jimmy White • john daly • mentmore bridge • railway detective • Roger Cordrey • Ronnie Biggs • Roy James • sears crossing • tom wisbey |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-070-8 / 1803990708 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-070-5 / 9781803990705 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich