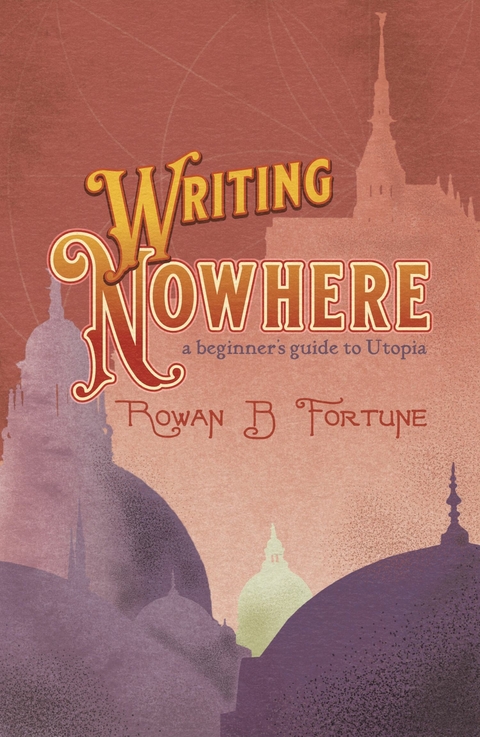

Writing Nowhere (eBook)

130 Seiten

Cinnamon Press (Verlag)

978-1-78864-802-8 (ISBN)

Rowan B Fortune is an author of strange utopias and gothic parables, a philosophical optimist in love with fiction's capacity to expose - paraphrasing Pascal - the extraordinary in the ordinary. Currently a denizen of London, Rowan haunts occult bookshops, hosts a socialist reading group and runs the editing service, Rowan Tree Editing. A former editor and writing mentor at Cinnamon Press, Rowan has a PhD in creative writing, specialising in utopian fiction.

Rowan B Fortune is an author of strange utopias and gothic parables, a philosophical optimist in love with fiction's capacity to expose — paraphrasing Pascal — the extraordinary in the ordinary. Currently a denizen of London, Rowan haunts occult bookshops, hosts a socialist reading group and runs the editing service, Rowan Tree Editing. A former editor and writing mentor at Cinnamon Press, Rowan has a PhD in creative writing, specialising in utopian fiction.

Chronology of Utopia

Having examined the genre of utopian writing, it is also important to consider its historicity, that is, the wider textual context from which the genre emerged and which shaped it. Doing this will demonstrate that Utopia is a genre of literature marked by a conversation between authors’ and further show how this genre developed from the early modern period to its current state. My condensed chronology will centre on key transitional texts that reshaped the conversation, such as Harrington’s Oceana. It will also be complemented by an in-depth comparison between Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward and William Morris’ News from Nowhere. First, however, it is helpful to start with More’s Utopia.

Navigating between ahistorical heuristics and radical historicisation, both of which risk loosing continuity by bracketing utopia completely or relinquishing the capacity to make generalisations about it, will be crucial to my approach. Fredric Jameson offers a systematic approach that does not allow for generalising from examples to support a coherent thesis: ‘For Jameson everything must be historicised; even historicism itself.’84 When reading utopias, this leads him to see More’s Utopia outside its historical situatedness, concluding that ‘More’s own prejudices seem to speak through the text’.85 For Kumar, however, this kind of reference to prejudice, psychology, etc. can lose sight of the very historical totality that Jameson, a Hegelian, studies. That is because everything is reduced to an irreducible instance of history, which cannot be compared without losing its historicity. Along with Kumar, I prefer a ‘preoccupation with certain characteristic problems and the continuous argument about the best possible solutions to them. All this suggests a tradition.’86 Historically embedded, tradition and genre can imply both change and meaningful continuity. Both are abstractions, and to some extent arbitrary, but without them it is impossible to find an anchorage in something as potentially broad as the utopian writing.

The Renaissance humanist and martyred saint, More, offers a good point of departure for the utopia within this chronological conversation. As Kumar stresses, More influenced the entire genre, beginning with books such as Tommaso Campanella’s The City of the Sun (1602)87 and proceeding to:

[…] Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621-1638),88 which has been called ‘the first proper utopia written in English’. The seventeenth-century classic not merely critically reviewed the utopias of More, Andrea, Campanella and Bacon; it also presented its own utopia: ‘a New Atlantis, a poetical commonwealth of mine own’.89

The briefest survey of titles establishes More’s impact: see William Morris’s News from Nowhere, ‘nowhere’ constituting the meaning of ‘utopia’; Samuel Butler’s anti-utopia Erewhon (1872),90 an anagram of ‘nowhere’, and H. G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1905).91 Eric Hobsbawm traces More’s far-reaching sway so that, by the nineteenth-century, utopia ‘became the term used to describe any attempt to sketch the ideal society of the future’.92 This constitutes a tendency to dilute the meaning of the genre that my analysis resists, as was argued for in the previous section.

In addition to giving the genre its name, More provided its generic content, the aforementioned subjects of economy, reproduction, education and religion. His approach to these subjects has been problematised as the then embryonic conversation between texts grew, and we can see from the genre’s beginning serious limitations to utopianism. L. T. Sargent, for example, has uncovered a colonialist attitude, one that represents a repressed continuity within the genre beginning with More and continuing to:

[…] Theodor Hertzka’s Freiland: Ein sociales Zukunftsbild (1890) that envisioned the displacement of the indigenous population to create the utopia[…] And James Burgh’s 1764 An Account of the First Settlement, Laws, Form of Government, and Police, of the Cessares, A People of South America concerns the establishment of a Protestant colony in an ‘uninhabited’ area of South America. Also, Robert Pemberton’s 1854 The Happy Colony specifies the creation of a community in an area of New Zealand that was heavily populated by Maori as if there was no one there at all[…] None of these works considered the people living on the land or their displacement as relevant.93

Colonialism is an important subject to be addressed in the ustopia, which represents the dystopian side of the original utopian dream.

Religion, another fraught subject for modernity, is at stake during the formation of utopia too: ‘More’s Utopia was closely followed by Johann Eberlin von Günzburg’s pamphlet series Die fünfzehn Bundesgenossen (1521). Embedded in the series is Eberlin’s ideal city state, Wolfaria, today acknowledged as the first Protestant utopia.’94 Leaving the sixteenth-century, the Lutheran Christianopolis (1619)95 by Johann Valentin Andraea and Giovanni Botero’s similar Reason of State (1589) were influenced by Eberlin’s explicitly religious utopias.96 Utopianism began at the very moment when religion in Europe was destabilised and contested by the emerging Reformation and Counter-Reformation, so More’s subject, admittedly secularised by depicting the utopians as pagan, inevitably played into these tensions. Revealing the links between religious and political themes and utopianism, Mark Goldie elucidates how Catholicism:

[…] was not above using Machiavelli’s vaunting of Rome’s pagan patriotic religion as a model for a portrayal of Christianity as the patriotic religion of the Bishop of Rome’s imperium. The genre began with Botero’s Reason of State (1589), and was most influential in the writings of Tomasso Campanella. Protestant philosophers turned these claims on their head, or, rather, turned them right side up. The Lutheran Platonist utopias of north Germany, such as J. V. Andraea’s Christianopolis (1619), are, in this task of inversion, at one with Harrington’s Oceana.97

Goldie makes clear that the religious wars and the rise of a new, secular politics simultaneously shaped a genre that depicted idealised societies.

It is wrong to posit More as fully circumscribing the genre; new and subordinated contestations fed into this imaginative territory, even if More serves as the progenitor. In contrast to many utopias, François Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel (1534) reconceives the monastic ideal in hedonistic and liberated terms, foreshadowing anarchist and libertarian ideal societies that More did not suggest: ‘In their rule was only this clause:/ DO WHAT YOU WILL’.98

For Pohl, utopianism during the disruptions of the English Civil War ‘provided a space for women writers.’99 She cites Mary Cary’s, A New and More Exact Mappe; or, Description of New Jerusalems Glory (1651)’,100 which also anticipates Cavendish’s Blazing World (1666). The role of feminism in utopianism is examined later as the concerns of women remain largely suppressed in the genre through the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, with these honourable exceptions.

The outlandishness of Cavendish’s travel to another world, via the North Pole, also anticipates soft science fiction and occurs in a context in which fantastical adventures represented another distinct current, a spin-off genre, from More’s earthly Utopia. This was especially represented in the prolific lunar novels that often have more in common with mythic ideal world stories than utopias, as Pohl suggests:

Godwin’s work influenced John Wilkins to revise his The Discovery of a World in the Moone: or, A Discourse Tending to Prove, That, ‘Tis Probable There May Be Another Habitable World in That Planet (1638) and A Discourse Concerning a New World & Another Planet (1640). Both Godwin’s and Wilkins’s works were imitated in several important ways in Cyrano de Bergerac’s Histoire comique contenant les États et Empires de la Lune (1657).101

Other unusual utopias written during the seventeenth-century give a sense of the diversity of the period. Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627) is an example of a scientific utopia involving mastery of the natural world: ‘The End of our Foundation is the knowledge of Causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible.’102 Bacon begins to anticipate the return of the Cockaygne myth in the more contemporary post-scarcity, technological ideal-societies.

With the eighteenth-century rise of the uchronias or chronological...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.10.2020 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Sprachwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Creative Writing • Futurology • how to • Politics • Sociology • Speculative Fiction • speculative fiction. science fiction • Utopia • utopian studies • utopia, utopian studies, futurology, creative writing, speculative fiction. science fiction, politics, sociology, how to |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78864-802-1 / 1788648021 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78864-802-8 / 9781788648028 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 376 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich