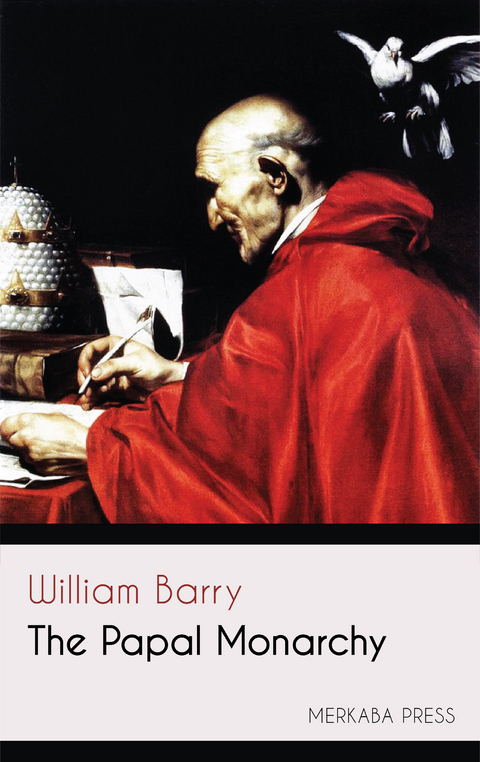

The Papal Monarchy (eBook)

155 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-002522-7 (ISBN)

IN the night of the 24th of August, 410, Alaric, King of the Western Goths, entered Rome with his army, by the Salarian Gate -- outside of which Hannibal had encamped long ago--and took the Imperial City. Eleven hundred and sixty-four years had passed since its legendary foundation under Romulus; four hundred and forty-one since the battle of Actium, which made Augustus Lord in deed, if not in name, of the Roman world. When the Gothic trump sounded at midnight, it announced that ancient history had come to an end, and that our modern time was born. St. Jerome, who in his cell at Bethlehem saw the Capitol given over to fire and flame, was justified from an historical point of view when he wrote to the noble virgin Demetrias, 'Thy city, once the head of the universe, is the sepulchre of the Roman people.' Even in that age of immense and growing confusion, the nations held their breath when these tidings broke upon them. Adherents of the classic religion who still survived felt in them a judgment of the gods; they charged on Christians the long sequel of calamities which had come down upon the once invincible Empire. Christians retorted that its fall was the chastisement of idolatry. And their supreme philosopher, the African Father St. Augustine, wrote his monumental work, 'Of the City of God,' by way of proving that there was a Divine kingdom which heathen Rome could persecute in the martyrs, but the final triumph of which it could never prevent. This magnificent conception, wrought out in a vein of prophecy, and with an eloquence which has not lost its power, furnished to succeeding times an Apocalypse no less than a justification of the Gospel. Instead of heathen Rome, it set up an ideal Christendom. But the center, the meeting-place, of old and new, was the City on the Seven Hills...

ORIGINS (B.C. 753-A.D. 67)

IN the night of the 24th of August, 410, Alaric, King of the Western Goths, entered Rome with his army, by the Salarian Gate -- outside of which Hannibal had encamped long ago--and took the Imperial City. Eleven hundred and sixty-four years had passed since its legendary foundation under Romulus; four hundred and forty-one since the battle of Actium, which made Augustus Lord in deed, if not in name, of the Roman world. When the Gothic trump sounded at midnight, it announced that ancient history had come to an end, and that our modern time was born. St. Jerome, who in his cell at Bethlehem saw the Capitol given over to fire and flame, was justified from an historical point of view when he wrote to the noble virgin Demetrias, "Thy city, once the head of the universe, is the sepulchre of the Roman people." Even in that age of immense and growing confusion, the nations held their breath when these tidings broke upon them. Adherents of the classic religion who still survived felt in them a judgment of the gods; they charged on Christians the long sequel of calamities which had come down upon the once invincible Empire. Christians retorted that its fall was the chastisement of idolatry. And their supreme philosopher, the African Father St. Augustine, wrote his monumental work, "Of the City of God," by way of proving that there was a Divine kingdom which heathen Rome could persecute in the martyrs, but the final triumph of which it could never prevent. This magnificent conception, wrought out in a vein of prophecy, and with an eloquence which has not lost its power, furnished to succeeding times an Apocalypse no less than a justification of the Gospel. Instead of heathen Rome, it set up an ideal Christendom. But the center, the meeting-place, of old and new, was the City on the Seven Hills.

To the Roman Empire succeeded the Papal Monarchy. The Pope called himself Pontifex Maximus; and if this hieratic name--the oldest in Europe --signifies "the priest that offered sacrifice on the Sublician bridge," it denotes, in a curious symbolic fashion, what the Papacy was destined to achieve, as well as the inward strength on which it relied, during the thousand years that stretch between the invasion of the Barbarians and the Renaissance. When we speak of the Middle Ages we mean this second, spiritual and Christian Rome, in conflict with the Northern tribes and then their teacher; the mother of civilization, the source to Western peoples of religion, law, and order, of learning, art, and civic institutions. It became to them what Delphi had been to the Greeks, and especially to the Dorians, an oracle which decided the issues of peace and war, which held them in a common brotherhood, and which never ceased to be a rallying point amid their fiercest dissensions. Thus it gave to the multitude of tribes which wandered or settled down within the boundaries of the West, from Lithuania to Ireland, from Illyria to Portugal, and from Sicily to the North Cape, a brain, a conscience, and an imagination, which at length transformed them into the Christendom that Augustine had foreseen.

If the Papacy were blotted out from the world's chronicle, the Middle Ages would vanish along with it. But modern Europe cannot be deduced, as was thought in the last century by, writers like Voltaire and Montesquieu, from Augustan Rome, with no regard for the long transition which connects them together. It is in this way that the medieval Popes take their place in the Story of the Nations; they continue the Roman history; they account in no small degree for the institutions under which we are living; and their fortunes, so exalted, so unhappy, and not seldom so tragical, shape themselves into a drama, the scenes and vicissitudes of which are as highly romantic as they are expressive of one great ruling idea.

The stage on which this mighty miracle-play was enacted, though spacious, was well defined. Our direct concern will not be with any dogmatic or strictly religious claims put forth by the Popes-- these belong to the theologian--but with the sovereignty which they exercised, the nations affected by their decretals, the Holy Roman Empire which their word called into being, and the kingdoms which gladly or reluctantly acknowledged in them a feudal lordship. Thus their dominion never, if we except passing interludes, went beyond the old Patriarchate of the West, as recognized at the Council of Nicæa. Not even the haughtiest Pontiffs pretended to make or unmake the Byzantine Emperors. They dealt otherwise with the Frankish or Suabian chiefs, whom they anointed, crowned, excommunicated, and deposed at the tomb of the Apostles. But until Gregory II. in 731 cast off his allegiance, they had been subjects, not suzerains, of Constantinople. With Latin Emperors they felt themselves able to cope; but the majesty of that earlier Rome lingered yet on the shores of the Bosporus; and the Papal Monarchy vails its crest before it, unless when the Franks have usurped a precarious and hateful power in Byzance after the Fourth Crusade, or the Normans and Venetians divide between them the strong places of Attica and the Morea. Always the Pope is Western, not Eastern, though he may become a slave of the palace during the two hundred years which follow on the conquest of Italy by Belisarius. Yet even in that period of depression he was slowly winning ground outside the Empire, and every tribe made Christian was bringing a fresh stone to build up the arch of the Papal power, fated for so long to stride visibly across the kingdoms of Europe.

Had the Emperors of the East known how to withstand the onset of those hordes which streamed down over the Alps; could they have overthrown or subdued the Lombards, and so kept the Pepins and Charlemagnes at home, it may be questioned whether any Pope would have dreamt of playing the great part in politics which was found inviting or inevitable as time went on. But the old Empire shrank to the Exarchate of Ravenna; it could barely maintain itself on the edge of the Ionian Sea. The Pontiff, looking round for help against the now converted but always detestable Longbeards of Pavia, signaled to the most daring of the new Christian nations. Pepin answered his call; overcame Astolphus; bestowed on St. Peter a patrimony in lands, serfs, and cities; and paved the way for his son's coronation in 800 as Emperor of the West. He certainly did not foresee that the "Sacerdotium" and the "Imperium" -- those divided members which in heathen Rome had been united in the same person-- would struggle during the next seven hundred years in a doubtful contest, until both sank exhausted and the. Reformation broke Christendom in twain. As there is a unity of place, determined by the bounds of the Lower Greek Empire, which includes this vast and exceedingly human series of transactions, so there is a unity of time, but as might be expected, not marked by such definite limits. St. Gregory the Great is its herald and anticipation; Boniface VIII. brings it to a close. But as several centuries take us slowly on to the culminating point, so the fourteenth and fifteenth lead us downwards again until the idea of an Imperial Papal Christendom has spent its force. The Lateran Monarchy stood at its height during some two hundred years -- from Gregory VII. to Innocent III., or perhaps to Gregory X. (1073-1274). Its creative influence, if we regard European civilization as a whole, had begun sooner and lasted longer; it was often visible at the extremities when Rome itself had sunk into a strange barbarism. Its spiritual energy neither rose nor fell in exact proportion to the outward splendor of the Holy See, as many instances will prove in the pages that follow.

But another condition of this second rise to greatness on the part of Rome has been often overlooked. If St. Peter was considered to be the spiritual founder of the Papacy, and if the Emperor Constantine, by removing the seat of government to the Golden Horn, had left it room in which to expand, yet the marvelous apparition of Mohammed, and the conquests of his lieutenants or successors, broke the power of the Christian East, and in so doing allowed the West time to develop without hindrance on its own lines. The Caliphate bears, indeed, more than one point of resemblance, external at least, to the dynasty of the Vicars of Christ established in Rome. But it is the long series of invasions, stripping off province after province from the weak Emperors of Byzantium, laying waste the churches of Syria and Egypt, reducing the Patriarchates of Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem to barren names, and thus abolishing the older forms of the Christian polity, which we have now in view. Straightway, the fame and consequence of the one remaining Patriarch who dated from Apostolic times must have been indefinitely enhanced. The Pope became, as a great Catholic genius has written, "heir by default" of antiquity. Those Sees, and, above all, the See of Alexandria, which had shared with him in political prestige, and could never be denied a voice when there was question of dogma or discipline, had passed for ever beneath the Moslem yoke. And the Bishop of Constantinople was but the Emperor's chaplain, incapable of pursuing a course for himself--the nominee, the puppet, and sometimes the prisoner of one who claimed in his own person to be most sacred, a Divine delegate, and a god on earth. In Rome the Bishop had no rival or second. He tended more and more to become what Cæsar had been of old, the embodied city, with all its mysterious charm, its predestination to supreme command, its unique and indelible character as a shrine or temple of deity. From the seventh century onwards, Rome appeared in men's eyes to be the Apostolic...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.8.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-002522-4 / 0000025224 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-002522-7 / 9780000025227 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 333 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich