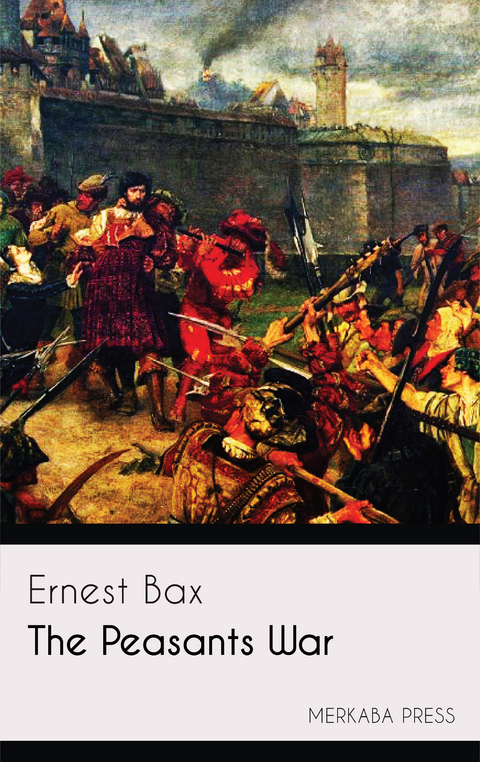

The Peasants War (eBook)

175 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-002524-1 (ISBN)

The time was out of joint in a very literal sense of that somewhat hackneyed phrase. Every established institution - political, social, and religious - was shaken and showed the rents and fissures caused by time and by the growth of a new life underneath it. The empire - the Holy Roman - was in a parlous way as regarded its cohesion. The power of the princes, the representatives of local centralised authority, was proving itself too strong for the power of the emperor, the recognised representative of centralised authority for the whole German-speaking world. This meant the undermining and eventual disruption of the smaller social and political unities,(2) the knightly manors with the privileges attached to the knightly class generally. The knighthood, or lower nobility, had acted as a sort of buffer between the princes of the empire and the imperial power, to which they often looked for protection against their immediate overlord or their powerful neighbour - the prince. The imperial power, in consequence, found the lower nobility a bulwark against its princely vassals. Economic changes, the suddenly increased demand for money owing to the rise of the 'world-market,' new inventions in the art of war, new methods of fighting, the rapidly growing importance of artillery and the increase of the mercenary soldiery, had rendered the lower nobility, as an institution, a factor in the political situation which was fast becoming negligible. The abortive campaign of Franz von Sickingen in 1523 only showed its hopeless weakness. The 'Reichsregiment,' or imperial governing council, a body instituted by Maximilian, had lamentably failed to effect anything; towards cementing together the various parts of the unwieldy fabric. Finally, at the 'Reichstag' held in Nürnberg, in December, 1522, at which all the estates were represented, the 'Reichsregiment,' to all intents and purposes, collapsed...

The Outbreak of the Peasants War

THE growing discontent among the peasantry had led to many an attempt to curtail the right of assembly in the rural districts throughout Germany. These attempts were specially aimed at the popular merry-makings and festivals which brought the inhabitants of. Different parishes together. Weddings, pilgrimages, church-ales (kirchweihen), guild-feasts, etc., were sought to be suppressed or curtailed in many places. Even the ancient right of the village assembly was entrenched upon, or, in some cases, altogether withdrawn. But it was all of no avail. The fermentation continued to grow. From the spring of 1524 onwards, sporadic disturbances took place on various manors throughout the country. In many places tithes(1) were refused.

The first serious outbreak occurred in August, 1524, in the Rhine valley, in the Black Forest, at Stühlingen, on the domains of the Count of Lupfen, and the immediate cause is said to have been trivial exactions on the part of the countess. She required her tenants on some church holiday to gather strawberries and to collect snail shells on which to wind her skeins after spinning.(2) This slight impost evoked a spark that speedily became a flame running through all the neighbouring manors, where the various forms of corvée and dues were simultaneously refused. A leader suddenly appeared in one Hans Müller, a former soldier of fortune, who was a native of the village of Bulgenbach, belonging to the monastery of St. Blasien. A flag of the imperial colours, black, red and yellow, was made, and on St. Bartholomew’s Day, the 24th August, Hans Müller at the head of 1,200 peasants marched to Waldshut under cover of a church-ale which was being held in that town.

Waldshut, which constituted the most eastern of the four so-called “forest towns” — the others being Laufenburg, Säkingen and Rheinfelden — was, at this moment, in strained relations with the Austrian authorities.

The peasants fraternised with the inhabitants of the little town, and the first “Evangelical Brotherhood” sprang into existence.(3) Every member of this organisation was required to contribute a small coin weekly to defray the expenses of the bearers of the secret despatches, which were to be distributed far and wide throughout Germany, inciting to amalgamation and a general rising. Throughout the districts of Baden in the Black Forest, throughout Elsass, the Rhein, the Mosel territories, as far as Thuringia, the message ran: no lord should there be but the emperor, to whom proper tribute should be rendered, on the guarantee of their ancient rights, but all castles and monasteries should be destroyed together with their charters and their jurisdictions.

As soon as the news of the agitation reached the Swabian League, unsuccessful attempts at pacification were made. The Swabian League, it must be premised, was a federation of princes, barons and towns, whose function was keeping up an armed force for the main purpose of seeing that imperial decrees were carried out, and for preserving public tranquillity generally. It was really the only effective instrument of imperial power that existed. As we shall presently see, it was this Swabian League that chiefly contributed to crushing the peasant revolt throughout southern Germany. Meanwhile the forces of Hans Muller were growing, until by the middle of October well-nigh 5,000 men were ranged under the black, red and gold banner. At the same time, the troops at the disposal of the nobility within the revolting area were altogether inadequate to cope with the situation. In the districts of the Black Forest and elsewhere, the Italian War of Charles V. had drained off the best and most numerous of the fighting men.

After marching through the neighbouring districts with his peasant army, whose weapons consisted largely of pitchforks, scythes and axes, proclaiming the principles and the objects of the revolt, Hans Müller withdrew into a safe retreat in the neighbourhood of the village of Rietheim on learning that a small force of about a thousand men had been got together against him. The winter was now fast approaching, and it did not appear to the aristocratic party desirable for the time being to pursue matters any further in the direction of open hostilities. Accordingly Hans von Friedingen, the Chancellor of the Bishop of Constanz, with three other gentlemen, proceeded to the camp of the peasants to attempt a negotiation. They succeeded in persuading the insurgents to disperse on the understanding that the lords specially inculpated should agree to consider proposals from their tenants, and that, failing an agreement on this basis, the matters in dispute should be referred to an independent tribunal, the district court of Stockach being suggested. A basis of agreement drawn up between the Count of Lupfen and his tenants contains some curious provisions; while fishing was prohibited, a pregnant woman having a strong desire for a fish was to be supplied with one by the bailiff. Bears and wolves were declared free game, but the heads were to be reserved for the lord, and in the case of bears one of the paws as well. Meanwhile, the towns of northern Switzerland, in whose territories an agitation was also proceeding, began to get alarmed and to warn the Black Forest bands off their territories. Switzerland herself was at this time in the throes of the Reformation, and in the neighbouring lands of the St. Gallen Monastery a vehement agitation was going on. No attempt, however, was made by the German peasants to pass over into Swiss territory, although it seems to have been more than once threatened. Zürich, Schaffhausen, and other Swiss cantons, indeed, in the earlier phases of the Peasants War, endeavoured to effect a mediation between the peasants and their lords. They were partly afraid of the agitation taking dangerous form with their own peasants and partly regarded the movement as belonging to the religious reformation, which had now taken root in northern Switzerland.

The following articles were agreed upon as the basis of negotiation by the united peasants of the Black Forest and the neighbouring lands of Southern Swabia, which were also now involved in the movement:-

1. The obligation to hunt or fish for the lord was to be abolished, and all game, likewise fishing, was to be declared free.

2. They should no longer be compelled to hang bells on their dogs’ necks.

3. They should be free to carry weapons.

4. They should not be liable to punishment from huntsmen and forest rangers.

5. They should no longer carry dung for their lord.

6. They should have neither to mow, reap, hew wood, nor carry trusses of hay nor firewood for the uses of the castle.

7. They were to be free of the heavy market tolls and handicraft taxes.

8. No one should be cast into the lord’s dungeon or otherwise imprisoned who could give guarantees for his appearance at the judicial bar.

9. They should no longer pay any tax, due, or charge whatsoever the right to which had not been judicially established.

10. No tithe of growing corn should be exacted, nor any agricultural corvée.

11. Neither man nor woman should be any longer punished for marrying without the permission of his or her lord.

12. The goods of suicides should no longer revert to the lord.

13. The lord should no longer inherit where relations of the deceased were living.

14. All bailiff rights...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.8.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-002524-0 / 0000025240 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-002524-1 / 9780000025241 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 268 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich