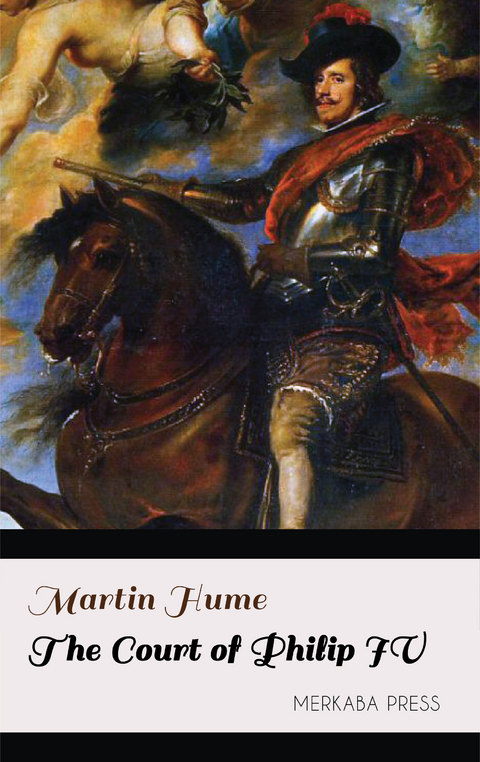

The Court of Philip IV (eBook)

249 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-002010-9 (ISBN)

'I lighted upon great files and heaps of papers and writings of all sorts.... In searching and turning over whereof, whilst I laboured till I sweat again, covered all over with dust, to gather fit matter together ... that noble Lord died, and my industry began to flag and wax cold in the business.'

Thus wrote William Camden with reference to his projected life of Lord Burghley, which was never written; and the words may be applied not inappropriately to the present book and its writer. Some years ago I passed many laborious months in archives and libraries at home and abroad, searching and transcribing contemporary papers for what I hoped to make a complete history of the long reign of Philip IV., during which the final seal of decline was stamped indelibly upon the proud Spanish empire handed down by the great Charles V. to his descendants. I had dreamed of writing a book which should not only be a social review of the period signalised by the triumph of French over Spanish influence in the civilisation of Europe, but also a political history of the wane and final disappearance of the prodigious national imposture that had enabled Spain, aided by the rivalries between other nations, to dominate the world for a century by moral force unsupported by any proportionate material power.

The sources to be studied for such a history were enormous in bulk and widely scattered, and I worked very hard at my self-set task. But at length I, too, began to wax faint-hearted; not, indeed, because my 'noble Lord had died'; for no individual lord, noble or ignoble, has ever done, or I suppose ever will do, anything for me or my books; but because I was told by those whose business it is to study his moods, that the only 'noble Lord' to whom I look for patronage, namely the sympathetic public in England and the United States that buys and reads my books, had somewhat changed his tastes. He wanted to know and understand, I was told, more about the human beings who personified the events of history, than about the plans of the battles they fought. He wanted to draw aside the impersonal veil which historians had interposed between him and the men and women whose lives made up the world of long ago; to see the great ones in their habits as they lived, to witness their sports, to listen to their words, to read their private letters, and with these advantages to obtain the key to their hearts and to get behind their minds; and so to learn history through the human actors, rather than dimly divine the human actors by means of the events of their times. In fact, he cared no longer, I was told, for the stately three-decker histories which occupied half a lifetime to write, and are now for the most part relegated, in handsome leather bindings, to the least frequented shelves of dusty libraries.

I therefore decided to reduce my plan to more modest proportions, and to present not a universal history of the period of Spain's decline, but rather a series of pictures chronologically arranged of the life and surroundings of the 'Planet King' Philip IV.-that monarch with the long, tragic, uncanny face, whose impassive mask and the raging soul within, the greatest portrait painter of all time limned with merciless fidelity from the King's callow youth to his sin-seared age. I have adopted this method of writing a history of the reign, because the great wars throughout Europe in which Spain took a leading part, under Philip and his successor, have already been described in fullest details by eminent writers in every civilised language, and because I conceive that the truest understanding of the broader phenomena of the period may be gained by an intimate study of the mode of life and ruling sentiments of the King and his Court, at a time when they were the human embodiment, and Madrid the phosphorescent focus, of a great nation's decay.

CHAPTER II

ACCESSION OF PHILIP IV.—OLIVARES THE VICE-KING—CONDITION OF THE COUNTRY—MEASURES ADOPTED BY THE NEW KING—RETRENCHMENT—MODE OF LIFE OF PHILIP AND HIS MINISTER—PHILIP'S IDLENESS—HIS APOLOGIA—DISSOLUTENESS OF THE CAPITAL—VILLA MEDIANA—THE AMUSEMENTS OF THE KING AND COURT—A SUMPTUOUS SHOW—ARRIVAL OF THE PRINCE OF WALES IN MADRID—HIS PROCEEDINGS—OLIVARES AND BUCKINGHAM

Prince Philip lay in his great square tentlike bedstead in the palace of Madrid, at nine o'clock on the morning of the 31st March 1621, when an usher announced his Dominican confessor, Sotomayor. The friar entered, and, kneeling by the bedside with a grave face, saluted his new sovereign as King Philip IV. For a moment the boy was overwhelmed at the long-looked-for news, and bade the attendants draw the curtains close that he might indulge his grief unseen. But soon the eager worshippers of the risen sun flocked into the room to pay their court to the new monarch when he should deign to show his face. Anon there was stir in the antechamber, and the crowd divided, bowing low as the stern, masterful man who was now lord over all stalked through the room, accompanied by his aged uncle the white-haired Don Baltasar de Zuñiga, destined by him to be nominally the King's chief minister, behind whom Olivares might rule unchecked. Advancing to the King's bed, Olivares threw back the curtains and peremptorily told Philip that he must get up, for there was much to be done. Uceda was still officially first minister and great chamberlain, with right of free access to the Sovereign; but when, a few moments later, he and his secretary entered the antechamber, amidst the scarcely concealed sneers of the courtiers, and the whisper reached Philip that they were coming, the King leapt from his bed and cried out that no one else was to be admitted until he was dressed.

Dressing on this occasion was a long process, for the young King broke down with grief and excitement several times whilst his attendants were preparing him for public audience; and Uceda, in the antechamber, fumed and fretted at the insult put upon him by the King, who thus disregarded his father's dying injunctions in the first moments of his bereavement. Whilst Uceda awaited the King's pleasure, Olivares, leaving the bed-chamber, met his falling rival face to face, and a violent altercation took place as to the premature action of Philip in ordering the Duke of Lerma, a Prince of the Church now, and immune from lay commands, to stay his journey to Madrid. Pointing to the State papers, seals, and keys in the hands of the secretary who accompanied him, Uceda asked who but the Duke of Lerma was worthy of taking charge of them. "My uncle, Don Baltasar de Zuñiga is here," replied Olivares, "to do so, and to give to the State the advantage of his long experience, and wisdom second to none." Uceda was then notified that the King, being dressed, would receive him; and entering the room, he knelt and proffered to Philip the seals and papers of his office. Pouting and frowning, the King waved his hand towards the sideboard, and said, "Put them there," and Uceda went out unthanked, to weep his now certain ruin and disgrace.

Whilst the King was busy condoling with his young wife and sister and his two brothers Carlos and Fernando, and receiving the homage of his nobles, the preparations were hastily made in the great hall of the Alcazar for the lying in state of the body of Philip III. in his habit as a friar of St. Francis. And as the muffled death bells boomed from the steeples of the capital, one man at least there was whose heart fainted at the sound. "The King is dead, and so am I," cried Don Rodrigo de Calderon from the prison where he had suffered and languished for years, the scapegoat for others, borne down by accusations innumerable, from theft to witchcraft and regicide. In his pride and power he had piled up wealth beyond compute, as his master Lerma had done, but it is clear now that the other charges against him were mainly false. His long trial had resulted in no mortal crime being proved, and had Philip III. lived he would doubtless have been pardoned; but he had belonged to the old greedy gang, and Olivares had no mercy upon them. Before Philip's nine days mourning reclusion in the monastery of St. Geronimo was ended a clean sweep was made of the men who had surrounded the dead King. Calderon's head fell on the scaffold in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid; the great Duke of Osuna, who had ruled Naples with so high a hand as to be accused of the wish to make himself a King, was incarcerated and persecuted till his proud heart broke; Uceda met with a similar fate; the powerful confessor Aliaga was disgraced and banished; and even Lerma was not spared, though he fought stoutly for his plunder; and all the clan of Sandoval and Rojas were trampled under the heels of the Guzmans and their allies.

The state of things which the new Sovereign had to face was positively appalling. The details of the abject penury and misery universal throughout Spain, except amongst those who managed the public revenues and their numerous hangers-on, sound almost incredible. Idleness and pretence were everywhere. Insolent gentlemen in velvet doublets and no shirts, workmen who strutted and clattered in ruffs and rapiers, seeking prey as sham soldiers instead of earning wages by honest handicrafts, led poets, and paid satirists, gamesters, swindlers, bravos and cutpurses, pretended students who lived like the rest of the idle crew on alms and effrontery, crowds of friars and priests whose only attraction to their cloth was the sloth which it excused; ladies, rouged and overdressed, who deliberately and purposely aped the look and manners of prostitutes,—these were the prevailing types of the capital, as described by eyewitnesses innumerable, as well as by the romancers who revelled in the colour, movement, and squalid picturesqueness of such a society. And to maintain the real and false splendour in Madrid the starving agriculturists, who had not abandoned their holdings in sheer despair, were ground down to their last real by the crushing alcabala tax, by local tolls and octrois, and by the heartless extortions of the tax farmers.

There is no doubt that, so far as their light extended, both the King and Olivares sincerely wished to reform abuses of which the results were patent to all. Young Philip himself was good hearted and kindly, as his father had been, but far more sensual and less devout in his habits. Though in public he assumed the marble gravity traditional thenceforward in Spanish kings, he was gay and witty in private discourse with those whose society he enjoyed, especially writers and players. His love of books, music, and pictures, as well as of poetry and the drama, made him, as time went on, the greatest patron of authors and artists in Spain's golden age of social and political decadence. But idleness marred all his qualities, and the lust for pleasure which he was powerless to resist made him the slave of favourites and his passions all his life. A man such as this, endowed with a gentle heart and a tender conscience, was doomed to a life of misery and remorse in the intervals of his thoughtless pleasures; and in the course of this book we shall see that sorrow ever followed close on joy's footsteps in the life of the "Planet King," until final ruin overtook the nation, cursed with the gayest and wickedest Court since that of Heliogabalus, and all was quenched in a great wave of tears.

The man to whom Philip handed his conscience, as has been described, on the first day of his reign, was nearly twenty years his senior. An indefatigable worker, with an ambition as voracious as his industry, Olivares was the exact reverse of the idle, courtly, conciliatory Lerma. His greed was not personal, as that of Lerma had been, though his love of power led him to absorb as many offices as he. He was vehement and voluble, arrogant and impatient even with the King, and impressed upon Philip incessantly the need for exertion on his own part. Able as he unquestionably was, he appraised his ability too highly, and contemned all opinions but his own; whilst his attitude towards the foreign Powers was insolent in the extreme, and quite unwarranted by Spain's position at the time. From an economic point of view, Olivares, though he began his rule by cutting down expenses in drastic fashion, was no wiser than his predecessors; though his ruling idea that the political unity of Spain was the thing primarily needful was sage and statesmanlike. But in this he was before his time, and his disregard for provincial traditions and rights in his determination to force unity of sacrifice upon the country, led to his own ruin and the disintegration of Spain. The portraits of him by Velazquez enable us to see the man as he lived,—stern, dark, and masterful, with bulging forehead and sunken eyes and mouth, his massive shoulders bowed by the weight of his ponderous head, we know instinctively that such a man would either dominate or die. He was the finest horseman in Spain, and he treated men as he treated his big-boned chargers, breaking them to obedience by force of will and persistence.

Such was the man who led Spain during the crucial period which was to decide, not only whether France or Spain should prevail politically, but whether the culture and civilisation of Europe should in future receive its impulse and colour from Spanish or French influences. In that great contest Spain was beaten, not so much because Olivares was inferior to Richelieu, as because of the old tradition that hampered Spain at home and abroad and pitted a decentralised country, where productive industry had been stifled and the sources of wealth choked, against a homogeneous nation where active...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-002010-9 / 0000020109 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-002010-9 / 9780000020109 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 376 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich