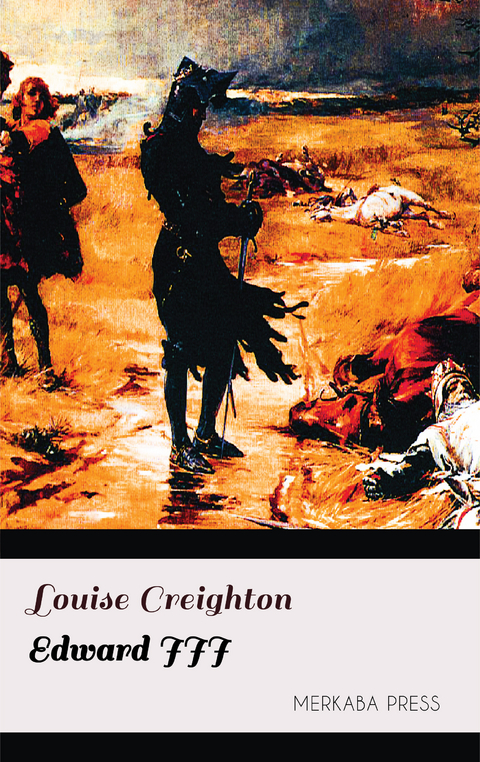

Edward III (eBook)

229 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001848-9 (ISBN)

On the 15th June, in the year 1330, there were great rejoicings in the Royal Palace of Woodstock. One Thomas Prior came hastening to the young King Edward III. to tell him that his Queen had just given birth to a son. The King in his joy granted the bearer of this good news an annual pension of forty marks. We can well imagine how he hurried to see his child. When he found him in the arms of his nurse, Joan of Oxford, overjoyed at the sight, he gave the good woman a pension of ten pounds a year, and granted the same sum to Matilda Plumtree, the rocker of the Prince's cradle.

Perhaps with Edward's thoughts of joy at the birth of his son were mingled some feelings of shame. It was three years since he had been crowned, and yet he was King only in name. He was nothing but a tool in the hands of his unscrupulous mother Isabella, and her ambitious favourite Mortimer. He was very young, not quite eighteen, and had not had sufficient knowledge or experience to know how to break the bonds within which he was held. But with the new dignity of father came to him a sense of his humiliating position. He would wish that his own son, on reviewing his youth, should have different thoughts of his father than he had...

Beginning of the French War.

The years from 1336 to 1338 had been spent by Edward III. in preparations for war. He had been endeavouring to gain allies amongst the princes on the Continent, his idea being to unite against France the rulers of the small principalities that lay to its north, such as Brabant, Gueldres, Hainault, and Namur. He also succeeded in gaining the alliance of the Emperor Louis of Bavaria. But his most important ally was Jacques van Arteveldt, the man who then ruled Flanders with the title of Ruwaert.

The condition of Flanders at that time was very strange. Since 877 Flanders had been ruled by a long succession of counts, who had done homage to the Kings of France for their country. The peculiar circumstances of the country, its mighty rivers, whose wide mouths afforded safe harbours for the ships, combined with the industry of the people, had early made Flanders important as a commercial and trading country. During the absence of the counts on the crusades, the towns had won for themselves many important privileges, and were really free communes, owning little more than a nominal allegiance to their duke. The kings of France eyed this wealthy and thriving province with great jealousy, and eagerly watched for an opportunity of asserting their authority over it. But till 1322 the people and their counts had been firmly united in resistance to France. Only with the accession of Count Louis de Nevers did the aspect of affairs change. This count had been brought up in France, and was imbued with French interests. He objected to the power and independence of the Flemish towns, and sought to oppress them in every way. He governed by French ministers, and called in French help against his own subjects. Then, when the people were oppressed, their industries ruined, their commerce at a standstill by the tyranny of their count, they found a leader in Jacques van Arteveldt, who showed them the way to liberty and prosperity. Against the firm union formed by the towns the Count of Flanders was powerless, and fled to the Court of France.

Under Arteveldt's care commerce and manufactures flourished, peace and prosperity reigned in the land, whilst there was no question of actual revolt from the authority of the count. Arteveldt only wished to show that the liberties of the people must be respected. Flanders was the great commercial centre of the MiddleAges, where merchants from far distant countries met and exchanged their goods.Arteveldt conceived the great idea, in which he was far beyond the intelligence of his time, of establishing free trade and neutrality as far as commerce was concerned. He was an important ally for Edward III. for many reasons. It was necessary for the interests of both peoples that Flanders and England should be friends; for in Flanders England found a sale for her wool, then the great source of her national wealth. From England alone could Flanders obtain this precious wool, which she manufactured into the famous Flemish cloth, and sent to all parts of the world. Edward III. recognised the wisdom and greatness of Arteveldt, and concluded a strong alliance with him for the benefit of both parties. On all occasions the English King treated the simple burgher of Ghent as an equal and a friend. It is not impossible that he gained in his intercourse with Arteveldt that feeling of the importance of commerce and industry which exercised so great an influence upon his legislation, and gained for him the title of the Father of English Commerce.

It was on the 16th July, 1338, that Edward III. sailed for Flanders. His first object was to meet his allies, the various princes of the Netherlands. He did not find them very eager for active co-operation in his undertaking. He determined to visit the Emperor in person, so as to prevail upon him to take an active part in the war. With this view he travelled up the Rhine, stopping first at Cöln, then a thriving commercial city, enjoying active intercourse with England. Here Edward stayed some days in the house of a wealthy burgher; the time passed in merriment and festivities, the King receiving visits from all the chief citizens. He visited most of the churches, and made offerings at the various altars; to the building fund of the great Cathedral he gave £67, a sum equal to £1,000 of our money. From Cöln he proceeded up the Rhine, his whole way being marked by continual festivities. At Bonn he stopped with one of the canons of the Cathedral, at Andemach with the Franciscans, and finally, on the 31st August, he reached Coblentz, where the German Diet was assembled. The Emperor received him in state in the market-place, seated on a throne twelve feet high, and by his side, though a little lower, was a seat for Edward. Around them stood a brilliant assembly; four of the electors were there, and wore the insignia of their rank. One of the nobles, as representative of the Duke of Brabant, held a naked sword high over the Emperor's head; 17,000 knights and gentlemen are said to have been present. In the presence of this imposing gathering Edward III. was created Vicar of the Empire for the west bank of the Rhine. In spite of this journey he obtained nothing from the Emperor but this empty title. On his return to Flanders he was so short of money that he had to pawn the crown jewels to the Bardi, the great Florentine merchants at Bruges. The allies were slow in bringing their forces into the field. Van Arteveldt refused to give Edward any active help, because of the oaths of fealty by which the Flemings were bound to Philip of Valois. At last Edward succeeded in collecting an army of 15,000 men, and met the French before Cambrai. The two armies parted without a battle, and Edward returned to Hainault. This fruitless campaign had exhausted his resources without gaining any result. He grew more anxious than ever for the help of Flanders, and made new proposals to the towns with magnificent offers.Arteveldt at last consented to help him, if he would assume the title of King of France; then the fealty which the towns owed to their suzerain could be transferred from Philip of Valois to Edward.

This, then, was the real cause of Edward's assuming the arms and title of the King of France; he did it only that he might gain the active help of the Flemings. As their suzerain he confirmed all the privileges of the towns, and granted them three great charters of liberties. These charters bear the impress of Arteveldt's mind, and are an expression of his commercial views. They proclaim liberty of commerce, the abolition of tailage (that is, of taxes upon merchandise), and a common currency. They guarantee also the security of merchandise, as well as of the persons of the merchants. The wool staple was fixed at Bruges; that is, Bruges was to be the place where alone wool might be imported, and be sold to the Flemish merchants. Edward returned to England to obtain the confirmation of these treaties by Parliament, as Arteveldt would not be content unless the Commons of England gave their consent to them. During his absence Queen Philippa remained at Ghent, and there gave birth to her third son John, who, from the city of his birth, was ever afterwards called John of Gaunt. Queen Philippa also acted as godmother toArteveldt's son, who was called Philip after her, and afterwards became famous, like his father, for defending the liberties of his country, though he did not show his father's wisdom and moderation.

Edward III obtained from the Parliament at Westminster the confirmation of his treaty with the Flemish towns, and also a new grant of supplies. This grant was for the most part in kind. The King was to have the ninth lamb, the ninth fleece, and the ninth sheaf; that is, in reality, a tenth part of the chief produce of the kingdom; for the tithe had first to be paid to the church, and so the ninth part of the remainder equalled the tithe. He was also allowed to levy a tax on the exportation of wool for two years. It shows the great popularity of the war that so large a grant was agreed upon. We also see the increasing power of Parliament, from the fact that Edward III. did not venture to impose any tax without its consent.

But in spite of all these grants Edward was still considerably in debt. He owed £9,000 to the merchants of Bruges and £18,100 to the association of German merchants in London, called the Hanseatic Steelyard, which had existed certainly since the time of Henry III., and had always been specially favoured by the English monarchs. But the merchants were always willing to lend him money, in return for the facilities which he gave to commerce. He was still obliged to pawn the crown jewels—his own crown was pawned to the city of Trier, and Queen Philippa's toCöln. Orders had to be given for the alteration of the royal seal; the lilies of France had to be incorporated with the leopard of England.

Meanwhile the French had gathered a large fleet, composed principally of Genoese ships, and were threatening the Flemish coast. There was danger of their cutting off intercourse between Antwerp and England. It was necessary for Edward to set off without delay. He hastily collected a fleet of some 200 sail, and started from Orewell, a port in Suffolk, on 22nd June, 1340. When the English fleet nearedSluys they saw standing before them, as Froissart tells us, "so many masts that they looked like a wood." This was the French fleet waiting to dispute the passage of the English. When Edward heard who they were, he exclaimed, "I have for a long time wished to meet with them; and now, please God and St. George, we will fight with them; for in truth they have done me so much mischief that I will be revenged on them if possible." The English fleet was arranged in[Pg 19]...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001848-1 / 0000018481 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001848-9 / 9780000018489 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 252 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich