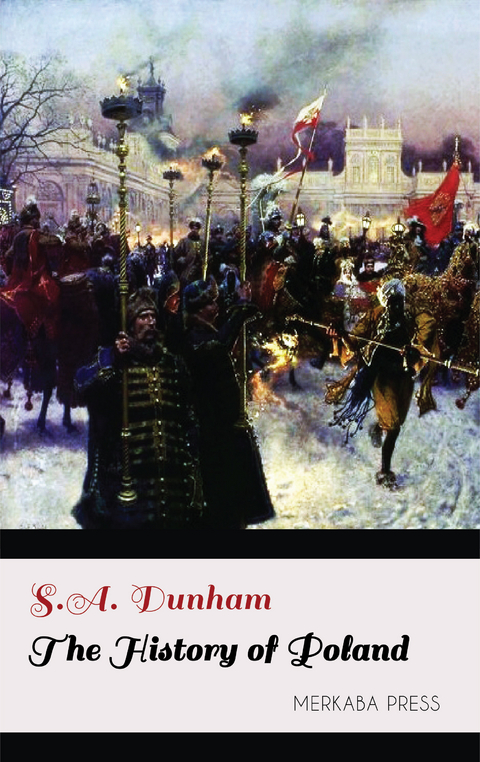

The History of Poland (eBook)

151 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001875-5 (ISBN)

Amidst the incessant influx of the Asiatic nations into Europe, during the slow decline of the Roman empire, and the migrations occasioned by their arrival, we should vainly attempt to trace the descent of the Poles. Whether they are derived from the Sarmatians, who, though likewise of Asiatic origin, were located on both sides of the Vistula long before the irruptions of the kindred barbarians, or from some horde of the latter, or, a still more probable hypothesis, from an amalgamation of the natives and new comers, must for ever remain doubtful. All that we can know with certainty is, that they formed part of the great Slavonic family which stretched from the Baltic to the Adriatic, and from the Elbe to the mouth of the Borysthenes. As vainly should we endeavour, from historic testimony alone, to ascertain the origin of this generic term slave, and the universality of its application. Conjecture may tell us, that as some of the more powerful tribes adopted it to denote their success in arms (its signification is glorious), other tribes, conceiving that their bravery entitled them to the same enviable appellation, assumed it likewise. It might thus become the common denomination of the old and new inhabitants, of the victors and the vanquished; the more readily, as most of the tribes comprehended under it well knew that the same cradle had once contained them. Other people, indeed, as the Huns or the Avars, subsequently arrived from more remote regions of Asia, and in the places where they forcibly settled, introduced a considerable modification of customs and of language: hence the diversity in both among the Slavonic nations-a diversity which has induced some writers to deny the identity of their common origin. But as, in the silence of history, affinity of language will best explain the kindred of nations, and will best assist us to trace their migrations, no fact can be more indisputable than that most of the tribes included in the generic term slavi were derived from the same common source, however various the respective periods of their arrival, and whatever changes were in consequence produced by struggles with the nations, by intestine wars, and by the irruption of other hordes dissimilar in manners and in speech. Between the Pole and the Russian is this kindred relation striking; and though it is fainter among the Hungarians from their incorporation with the followers of Attila, and among the Bohemians, from their long intercourse with the Teutonic nations, it is yet easily discernible...

MONARCHS OF THE HOUSE OF PIAST, 962-1139.

MIECISLAS I.

962-999.

This fifth prince of the house of Piast is entitled to the remembrance of posterity; not merely from his being the first Christian ruler of Poland, but from the success with which he abolished paganism, and enforced the observance of the new faith throughout his dominions. He who could effect so important a revolution without bloodshed, must have been no common character.

When the duke assumed the reins of sovereignty, both he and his subjects were strangers to Christianity, even by name. At that time almost all the kingdoms of the North were shrouded in idolatry: a small portion of Saxons, indeed, had just received the light of the Gospel, and so had some of the Hungarians; but its beams were as yet feeble, even in those countries, and were scarcely distinguishable amidst the Egyptian darkness around. Accident, if that term can be applied to an event in which Christian philosophers at least can recognise the hand of Heaven, is said to have occasioned his conversion. By the persuasion of his nobles, he demanded the hand of Dombrowka, daughter of Boleslas, king of Hungary. Both father and daughter refused to favour so near a connection with a pagan; but both declared, that if he would consent to embrace the faith of Christ his proposal would be accepted. After some deliberation he consented: he procured instructors, and was soon made acquainted with the doctrines which he was required to believe, and the duties he was bound to practise. The royal maiden was accordingly conducted to his capital [965]; and the day which witnessed his regeneration by the waters of baptism, also beheld him receive another sacrament, that of marriage.

The zeal with which Miecislas laboured for the conversion of his subjects, left no doubt of the sincerity of his own. Having dismissed his seven concubines, he issued an order for the destruction of the idols throughout the country. He appears to have been obeyed without much opposition. Some of the nobles, indeed, would have preserved their ancient altars from violation; but they dreaded the power of their duke, who, in his administration, exhibited a promptitude and vigour previously unknown, and who held an almost boundless sway over the bulk of the people. His measures seem at first to have been regarded with disapprobation; but the influence of his personal character secured the submission of the people, especially when they found that their deities were too weak to avenge themselves. The extirpation, however, of an idolatrous worship was not sufficient; the propagation of a pure one was the great task, a task which required the union of moderation with firmness, of patience with zeal. Happily they were found in the royal convert, and still more in his consort. Instructions were obtained from pope John XIII.; seven bishoprics, and two archbishoprics, all well endowed, attested the ardour and liberality of the duke. He even accompanied the harbingers of the Gospel into several parts of his dominions, aiding them by his authority, and inspiriting them by his example. By condescending to the use of persuasion, reasoning, remonstrance, the royal missionary effected more with his barbarous subjects than priest or prelate, though neither showed any lack of zeal, or paused in the good work. The duchess imitated his example; her sweetness of manner, her affability, her patience of contradiction, prevailed where an imperious behaviour would have failed.

The nobles, being the fewest in number, and the most easily swayed, were the first gained over. To prove their sincerity, when present at public worship, and just before the priest commenced reading the Gospel for, the day, at the intonation by the choir of the Gloria tibi, Domine! they half drew their sabres, thereby showing that they were ready to defend their new creed with their blood. Their example, the preaching of the missionaries, and, above all, the entire co-operation of their duke, at length prepared the minds of the people for the universal reception of Christianity; so that when he issued his edict in 980, that every Pole, who had not already submitted to the rite, should immediately repair to the waters of baptism, he was obeyed without murmuring. They were subsequently confirmed in the faith by the preaching of St. Adalbert, whose labours in Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, and Prussia, and whose martyrdom in the last-named country, then covered with the darkest paganism, have procured him a veneration in the north little less than apostolic.

When we consider the difficulties with which the new faith had to contend, among a people so deeply plunged in the vices inherent in their ancient superstitions, we shall not be surprised that fourteen years of assiduous exertions were required for so great a change; we shall rather be at a loss to account, on human grounds at least, for the comparative facility with which it was effected. Drunkenness, sensuality, rapes, plunder, bloodshed even at their entertainments, were things to which they had been addicted from time immemorial; and to be compelled to relinquish such enjoyments as these they naturally considered as a tyrannical interference with their liberties. The severe morality of the Gospel, and the still severer laws which the new prelates, or rather the duke, decreed to enforce it, must have been peculiarly obnoxious to men of strong passions, rendered stronger by long indulgence, and fiercely swayed by that impatience which is so characteristic of the Slavonic nations. If Miecislas was persuaded to dismiss his concubines, and thereby overcome his strongest propensity at the mere call of duty, more powerful motives were necessary with his subjects, if any faith is to be had in the statement of a contemporary writer. And, after all, the reformation in manners was very imperfect. It was probably on account of their vices that pope Benedict refused to erect Poland into a kingdom, though the honour was eagerly sought by the duke, and though it was granted at the same time to the Hungarians. There are not wanting writers to assert that the royal convert himself forfeited the grace of his baptism, and relapsed into his old enormities; but there appears little foundation for the statement.

While Miecislas was thus occupied in forwarding the conversion of the nation, he was not unfrequently called to defend it against the ambition or the jealousy of his neighbours. In 968 he was victorious over the Saxons, but desisted from hostilities at the imperial command of Otho I., whose feudatory he acknowledged himself. Against the son of that emperor, Otho II., he leagued himself with other princes who espoused the interests of Henry of Bavaria; but, like them, he was compelled to submit, and own not only the title but the supremacy of Otho, in 973. He encountered a more formidable competitor in the Russian grand duke, Uladimir the Great, who, after triumphing over the Greeks, invaded Poland in 986, and reduced several towns. The Bug now bounded the western conquests of the descendants of Ruric, whose object henceforth was to push them to the very confines of Germany. But Miecislas arrested, though he could not destroy, the torrent of invasion: if he procured no advantage over the Russian, he opposed a barrier which induced Uladimir to turn aside to enterprises which promised greater facility of success. His last expedition (989—991) was against Boleslas, duke of Bohemia. In this contest he was assisted with auxiliaries furnished by the emperor Otho III., whose favour he had won, and by other princes of the empire. After a short but destructive war, the Bohemian, unable to oppose the genius of Miecislas, sued for peace; but this triumph was fatal to the peace of the two countries. Hence the origin of lasting strife between two nations, whose descent, manners, and language were the same, and between whom, consequently, less animosity might have been expected.

But contiguity of situation is seldom, perhaps never, favourable to the harmony of nations. Silesia, which was the frontier province of Poland, was thenceforth exposed to the incursions of the Bohemians, and doomed to experience the curse of its limitrophic position.

Miecislas died in 999, universally regretted by his subjects.

BOLESLAS I.

999—1025.

BOLESLAS I., surnamed Chrobri, or the Lion-hearted, son of Miecislas and Dombrowka, ascended the ducal throne A.D. 999, in his thirty-second year, amidst the acclamations of his people.

From his infancy this prince had exhibited qualities of a high order,—great capacity of mind, undaunted courage, and an ardent zeal for his country’s glory. Humane, affable, generous, he was early the favourite of the Poles, whose affection he still further gained by innumerable acts of kindness to individuals. Unfortunately, however, his most splendid qualities were neutralised by his immoderate ambition, which, in the pursuit of its own gratification, too often disregarded the miseries it occasioned.

The fame of Boleslas having reached the ears of Otho III., that emperor, who was then in Italy, resolved, on his return to Germany, to take a route somewhat circuitous, and pay the prince a visit. He had before vowed a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Adalbert, whose hallowed remains had just been transported from...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001875-9 / 0000018759 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001875-5 / 9780000018755 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 326 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich