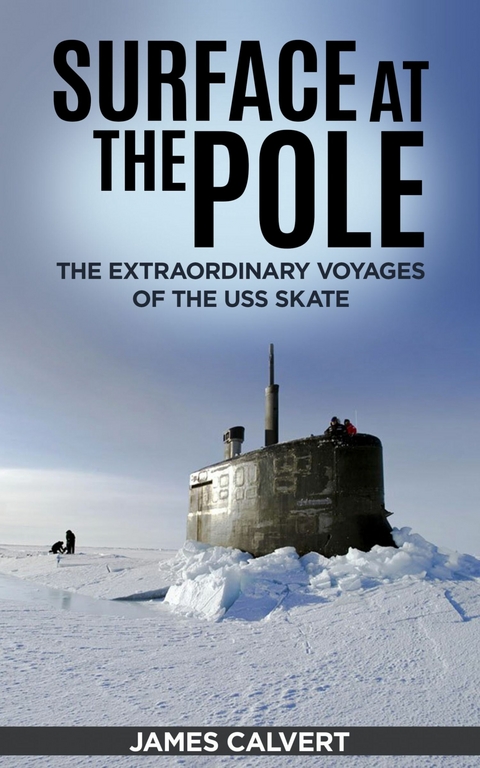

Surface at the Pole : The Extraordinary Voyages of the USS Skate (eBook)

197 Seiten

Bowsprit Books (Verlag)

978-0-359-15322-0 (ISBN)

The nuclear-powered USS Skate was the first submarine to break the surface of the North Pole. Author James Calvert captained the Skate and his book details a series of exploratory underwater voyages north before he and his crew finally found a way to the top and triumphantly smashed through the polar ice-cap on 17 March 1959.

This revised edition of Surface at the Pole: The Extraordinary Voyages of the USS Skate includes footnotes and images of the Skate.

The nuclear-powered USS Skate was the first submarine to break the surface of the North Pole. Author James Calvert captained the Skate and his book details a series of exploratory underwater voyages north before he and his crew finally found a way to the top and triumphantly smashed through the polar ice-cap on 17 March 1959.This revised edition of Surface at the Pole: The Extraordinary Voyages of the USS Skate includes footnotes and images of the Skate.

Chapter 1

IT WAS TEN O’CLOCK on a Sunday morning in August 1958. Around a small table in the center of a long, low, steel-walled room stood a group of four men, gazing intently at a moving pinpoint of light which shone like a glowworm through the glass table-top and the sheet of chart paper that covered it. One of the men followed the path of the light with a black pencil, adding to a web of similar markings already on the paper.

In one corner of this room, some 15 feet away from the group around the table, stood a second knot of men, their eyes fixed on a gray metal box suspended at eye level. Through a glass window on its face was visible the rapid oscillation of a metal stylus, inscribing two compact but irregular patterns of parallel lines across a slowly rolling paper tape. The stylus made a low whish, whish, whisk, like the sound of a whisk broom on felt, forming a background of noise in the otherwise quiet room.

The pattern on the tape looked like a range of mountains upside down. One of the men watching it broke the silence. “Heavy ice, ten feet,” he said laconically. At the plotting table, the black pencil line continued to follow the path of the moving light. Then the stylus pattern suddenly converged to a single narrow bar. “Clear water,” he called out. This time there was a poorly concealed trace of elation in his voice. At the plotting table, a small red cross was made over the pinpoint of light, completing a roughly rectangular pattern of similar crosses on the paper. And so the United States nuclear submarine Skate,* cruising slowly in the depths of the Arctic Ocean, completed preparations in an attempt to find her way to the surface deep within the permanent polar ice pack.

*Launched 16 May 1957, the Electric Boat-built USS Skate (SSN-578) was the third nuclear submarine commissioned by the US Navy.

Following image: USS Skate in Rotterdam, March 1958.

AS COMMANDER OF THE submarine, the next move was up to me. I studied the plotting paper closely, the looping black lines that marked the path of the submarine as she reconnoitered beneath the ice, the irregular rectangle of red crosses indicating the spots where the ice ended and open water began. The moving light, showing the position of the submarine on this underwater map, was just entering this rectangle.

“Speed?” I asked tensely.

“One-half knot,” came back the answer.

“Depth?”

“One eighty.”

“All back one-third,” I said, glancing toward the forward end of the room. There two men on heavy leather bucket seats sat before airplanelike control sticks with indented steering wheels mounted on hinged posts. One of these men now reached over and turned two knobs on the high bank of instruments in front of him, conveying my order to the engine room.

A slight quiver ran through the ship as her two 8-foot bronze propellers gently bit the water to bring us to a stop. I glanced nervously at the plotting paper again. The pinpoint of light was no longer moving. “Speed zero,” said the plotter.

“All stop,” I called out. The vibration of the propellers ceased. I stepped up on a low steel platform next to die plotting table. Two bright steel cylinders, 8 inches in diameter and about 4 feet apart, ran from wells cut in this platform up through watertight fittings in the overhead. “Up periscope. I’ll have a look.”

A slim, crew-cut crewman standing next to me reached up and pushed a lever. Hydraulic oil under heavy pressure hissed into the hoisting pistons. One of the steel cylinders began to rise out of its well, moving sluggishly against the pressure of the sea. Small drops of water ran down its shiny barrel from the overhead fitting. Finally the bottom of the cylinder, containing a pair of handles and an eyepiece, appeared from the well, rose to eye level, and sighed to a stop. I folded down the hinged metal handles and put my eye up to the rubber eyepiece of the periscope.

The clarity of the water and the amount of light were startling. At this same depth in the Atlantic the water looks black or at best a dark green, but here the sea was a pale and transparent blue like the lovely tropical waters off the Bahamas. I hooked my arm over the right handle of the periscope and tugged on it. At this depth—where a periscope is normally not used—it pressed heavily against its supporting bearing and could be turned only with great difficulty.

A blob of color came into the field of sight. I turned a knob on the periscope barrel to bring it into focus and found we had company. The ethereal, translucent shape of a jellyfish was swimming near the periscope, gracefully waving its rainbow-colored tentacles in the quiet water of a sea whose surface is forever protected from waves by its cover of ice.

I twisted the left handle of the periscope to shift the line of sight upward, in the hope that I could see the edge of the ice. The intensity of the light increased, but I could see nothing but a blurred aquamarine expanse. There was no ice in sight.

“Down periscope,” I said, folding the handles up. The crewman handled the hydraulic control carefully to prevent the sea pressure from slamming the periscope into the bottom of the well. I looked around the crowded control center of the submarine. Every face was turned questioningly toward mine.

“Nothing in sight but a jellyfish,” I said.

There was a nervous ripple of laughter which quickly disappeared.

“There’s a good bit of light here—we must be under some sort of an opening,” I went on. I glanced again at the plotting table. The pinpoint of light was resting squarely in the center of the rough rectangle of red marks.

“Do you think we’re moving at all?” asked the man who was operating the plotter.

“No way to tell for certain,” I answered. “Wait a minute, maybe there is. Up periscope.”

Again the hiss of oil under pressure accompanied the slow upward movement of the smoothly machined periscope barrel. Again I looked out into the icy water. There was our friend the jellyfish. I watched him for almost a minute without being able to detect any movement. “Down periscope. We’re stopped all right,” I said, explaining how I knew. “Our jellyfish friend is still looking down our periscope.”

There was another faint murmur of nervous laughter, but no breaking the air of tension in the quiet room. I turned toward the group of men around the ice-detecting instrument. They were gazing intently at the path of the sweeping stylus, apparently paying no attention to anything else. “How does it look?” I asked.

The man in charge of the group looked impassively in my direction. He held up his left hand with the index finger and thumb forming a circle and the remaining three fingers slightly raised.

Now was the time.

All eyes were on the men at the diving controls of the ship. Behind the two men in the leather bucket seats stood a blue-eyed lieutenant with short-cropped curly hair, the diving officer. He was responsible for holding the Skate in its motionless position 180 feet below the surface—a delicate and difficult task in itself.

It would be nothing compared to what he would now be called on to do. With a note of confidence in my voice that I didn’t really feel, I said to him: “Bring her up slowly to one hundred feet and stop her there.”

Following the intricate commands of the diving officer, a crewman standing by a long bank of control valves started to lighten the ship. The whir of a pump filled the room as seawater ballast was pumped out of tanks inside the ship. The three-thousand-ton submarine began to drift slowly upward like an enormous balloon. Our depth had been our assurance of safety from collision with the ice; now we were deliberately taking the ship up where danger lay. I noticed with annoyance that my mouth was dry and my heart was beginning to pound. In hope of making out our position as the ship moved upward, I ordered the periscope up again.

“Call out the depths as she comes up—I won’t be able to see the gauge,” I told the diving officer as I put my face to the eye-piece. There was nothing to be seen but water. Even the jellyfish was gone, left somewhere below us.

“One forty,” chanted the diving officer. This meant the top of the raised periscope, 60 feet higher than the keel, was only 80 feet below the surface; perhaps much less than that from the underside of the ice. I couldn’t understand why the ice was not yet visible.

The room was deathly quiet. The whish of the ice detector sounded strangely loud. I walked the periscope around in a complete circle, looking upward and all around. Nothing.

“One twenty.” The top of the periscope was only 60 feet below the surface. Suddenly I could see the outline of heavy ice nearby, rafted and twisted ice in huge blocks; and frighteningly close. I hastily turned the knob to swing the prism upward, but could see nothing but the same blurred aquamarine.

I held back an impulse to tell the diving officer to stop right there. I had asked for a gradual ascent to 100 feet, and if I ordered a sudden change it might upset the delicate distribution of ballast which enabled us to rise on an even keel. Already I could hear the noise of water flooding back into the tanks— the diving...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.10.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Anthologien |

| Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-359-15322-4 / 0359153224 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-359-15322-0 / 9780359153220 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 928 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich