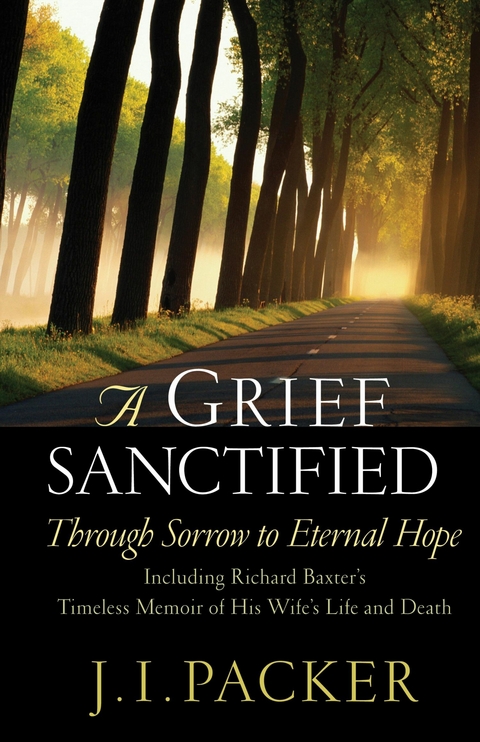

A Grief Sanctified (Including Richard Baxter's Timeless Memoir of His Wife's Life and Death) (eBook)

192 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-1642-9 (ISBN)

J. I. Packer (1926-2020) served as the Board of Governors' Professor of Theology at Regent College. He authored numerous books, including the classic bestseller Knowing God. Packer also served as general editor for the English Standard Version Bible and as theological editor for the ESV Study Bible.

J. I. Packer (1926–2020) served as the Board of Governors' Professor of Theology at Regent College. He authored numerous books, including the classic bestseller Knowing God. Packer also served as general editor for the English Standard Version Bible and as theological editor for the ESV Study Bible.

Grief

This is a book for Christian people about six of life’s realities—love, faith, death, grief, hope, and patience. Centrally, it is about grief.

What is grief? It can safely be said that everyone who is more than a year old knows something of grief by firsthand experience, but a clinical description will help us to get it in focus. Grief is the inward desolation that follows the losing of something or someone we loved—a child, a relative, an actual or anticipated life partner, a pet, a job, one’s home, one’s hopes, one’s health, or whatever.

Loved is the key word here. We lavish care and affection on what we love and those whom we love, and when we lose the beloved, the shock, the hurt, the sense of being hollowed out and crushed, the haunting, taunting memory of better days, the feeling of unreality and weakness and hopelessness, and the lack of power to think and plan for the new situation can be devastating.

Grief may be mild or intense, depending on our own emotional makeup and how deeply we invested ourselves in relating to the lost reality. Ordinarily, the most acute griefs are felt at times of bereavement, when old guilts and neglects come back to mind, and thoughts of what we could and should have done differently and better come hammering at our hearts like battering rams. When Shakespeare’s Romeo said, “He jests at scars, that never felt a wound,” he was thinking of the pangs of eros, but his words apply equally to the pangs of grief. Grief is thus, as we say, no laughing matter; in the most profound sense, it is just the reverse.

Bereavement, we said—meaning the loss through death of someone we loved—brings grief in its most acute and most disabling form, and coping with such grief is always a struggle. Bereavement becomes a supreme test of the quality of our faith. Faith, as the divine gift of trust in the triune Creator-Redeemer, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and so as a habit implanted in the Christian heart, is meant to act as our gyroscopic compass throughout life’s voyage and our stabilizer in life’s storms. However, bereavement shakes unbelievers and believers alike to the foundations of their being, and believers no less than others regularly find that the trauma of living through grief is profound and prolonged. The idea, sometimes voiced, that because Christians know death to be for believers the gate of glory, they will therefore not grieve at times of bereavement is inhuman nonsense.

Grief is the human system reacting to the pain of loss, and as such it is an inescapable reaction. Our part as Christians is not to forbid grief or to pretend it is not there, but to maintain humility and practice doxology as we live through it. Job is our model here. At the news that he had lost all his wealth and that his children were dead, he got up and tore his robe and shaved his head. Then he fell to the ground in worship and said, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I will depart. The LORD gave and the LORD has taken away; may the name of the LORD be praised” (Job 1:21 NIV). Managing grief in this way is, however, easier to talk about than to do; we are all bad at it, and for our own times of grieving we need all the help we can get.

At the heart of Richard Baxter’s grief book is an object lesson in what we may properly call grief management. Here we shall meet a grieving husband memorializing the soul mate whom, after nineteen years of marriage, he had tragically lost less than a month before. Margaret Baxter died at age forty-five after eleven days of delirium, her reason having almost wholly left her, as she had long feared it might do. A starvation diet had weakened her, and the barbarous routine of bloodletting, the universal seventeenth-century remedy for all disorders, had done her the reverse of good. A modern reader might guess that menopausal troubles were involved in her decline, but in her day the medical realities of menopause were unknown country.

Richard, her husband, twenty years older and a knowledgeable amateur physician, thought it was what she took over a period of time for her health (“Barnet waters” from Barnet spa north of London and “too much tincture of amber”) that brought on her death.1 “In depth of grief,”2 “under the power of melting grief,”3 Baxter resolved to write of her life, and within days produced a gem of Christian biography. It is at once a lover’s tribute to his fascinating though fragile mate and a pastor’s celebration of the grace of God in a fear-ridden, highly strung, oversensitive, painfully perfectionist soul. Baxter’s narrative is a classic of its kind and will help us in all sorts of ways.4

In 1681, when Richard wrote this Breviate (meaning “short account”) of Margaret’s life, he was probably the best known, and certainly the most prolific, of England’s Christian authors. Already in the 1650s, when despite chronic ill health he masterminded a tremendous spiritual surge in his small-town parish of Kidderminster, he had become a best-selling author and had produced enough volumes of doctrine, devotion, and debate to earn himself the nickname “Scribbling Dick.” Debarred in 1662 from parochial ministry by the unacceptable terms on which the Act of Uniformity reestablished the Church of England, he made writing his main business. By 1680, when he reached sixty-five, he had more than ninety publications to his name.

Then within six months came four bereavements.

In December 1680 “our dear friend” John Corbet, also an ejected minister and a close comrade of forty years’ standing, died. Corbet and his wife had lived in the Baxters’ home from 1670 to 1672. Baxter’s funeral sermon for Corbet testifies to their affection for each other,5 as did Margaret’s immediate persuasion of his widow to move back into the Baxter home on a permanent basis to be her personal companion.

Next, two members of what Richard called his “ancient family” finished their course: Mary, his stepmother, his father’s second wife, who had been living with them for a decade and had reached her mid-nineties, and “my old friend and housekeeper, Jane Matthews,” who had presided over his bachelor parsonage in Kidderminster and was now in her late seventies.

Finally on June 14, 1681, Margaret’s own life ended. As a pastor Baxter was, of course, used to dealing with deaths, but the cumulative strain of these four losses must have been considerable.

It should not surprise us that the distressed widower turned to a literary project for consolation and relief. He wrote very easily, and the writer’s discipline of getting things into shape is always therapeutic at times of emotional strain. Margaret’s will had called for a new edition of Baxter’s funeral sermon for Mary Hanmer (formerly Charlton), Margaret’s own mother. Baxter’s first thought was to bring out a volume in which he would prefix to that sermon four “breviates”—short lives of Mary Hanmer, Mary Baxter, Jane Matthews, and Margaret. Friends, however, persuaded him to drop the first three and cut out many personal details from his draft of the life of Margaret. “He was ‘loath to have cast by’ these ‘little private Histories of mine own Family,’ but he was ‘convinced’ by his friends . . . that his love and grief had led him to overestimate the value to others of what affected him so nearly.”6 Much, therefore, that we late-twentieth-century romantics, with our almost indecent interest in private lives, would like to know about “the occasions and inducements of [their] marriage” is lost to us. Nonetheless, the Breviate that finally emerged “is undoubtedly the finest of Baxter’s biographical pieces,”7 and one hopes that writing it benefited him as much as reading it can benefit us.

The personal memoir with a spiritual focus, a literary category pioneered by Athanasius’ Life of Antony and Augustine’s Confessions, was much more in evidence among the people of the Reformation after the mid-sixteenth century, Beza’s Life of Calvin and the stories of the martyrs in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments being among the more impressive examples. The seventeenth-century fashion of writing “characters”—literary profiles of human types and of particular individuals, viewed in lifestyle terms—further honed Puritan biographical skills. Baxter’s Breviate, though low-key and matter-of-fact in style, is Puritan spiritual storytelling at its best—storytelling that is made more poignant by Richard’s intermittent unveiling of his grief as he goes along. More will be said about this in due course.

C. S. Lewis’s Grief Book

“Mere Christianity”—meaning historic mainstream, Bible-based discipleship to Jesus Christ, without extras, omissions, diminutions, disproportions, or distortions—was Baxter’s own phrase for the faith he held and sought to spread. Three centuries after his time, C. S. Lewis used the same phrase as a title for the 1952 book in which he put together three sets of broadcast talks on Christian basics. Probably Lewis got the phrase from Baxter,8 and certainly in likening what he offered to the shared hallway off which open the rooms of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.9.2002 |

|---|---|

| Co-Autor | Richard Baxter |

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik |

| Schlagworte | Bereavement • Biography • Christ • Christianity • Christian Life • christian living • Commitment • Consolation • Death • Faith • faithfulness • God • gods love • gods plan • gods will • Grace • Grief • Healing • Hope • Jesus • Loss • Love • marriage • Memoir • Mercy • Nonfiction • Pastoral Care • Patience • Recovery • Redemption • relationships • relationship to God • Religion • Spirituality • spiritual journey • Starting over • Suffering • Theology • trust in God • widow • widower |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-1642-X / 143351642X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-1642-9 / 9781433516429 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 627 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich