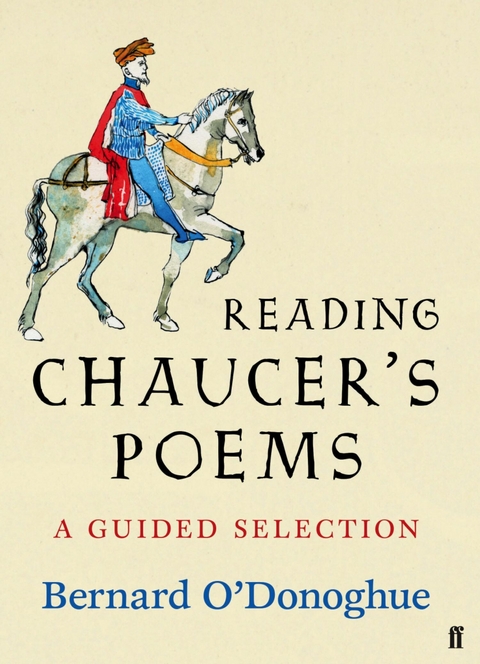

Reading Chaucer's Poems (eBook)

128 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-31496-6 (ISBN)

Bernard O'Donoghue was born in Cullen, Co Cork in 1945. He is an Emeritus Fellow of Wadham College, where he taught Medieval English and Modern Irish Poetry. He has published six collections of poetry, including Gunpowder, winner of the 1995 Whitbread Prize for Poetry, and The Seasons of Cullen Church, shortlisted for the 2016 T. S. Eliot Prize. His Selected Poems was published by Faber in 2008. He has published a verse translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Penguin Classics, 2006), and is currently translating Piers Plowman for Faber.

Geoffrey Chaucer is rightly regarded as the Father of English Literature. His observant wit, his narrative skill and characterization, his linguistic invention, have been a well from which the language's greatest writers have drawn: Shakespeare, Pope, Austen, Dickens among them. A courtier, a trade emissary and diplomat, he fought in the Hundred Years War and was captured and ransomed; his marriage into the family of John of Gaunt ensured his influence in political society. For more than a decade, he was engaged on his most famous work of all, The Canterbury Tales, until his death around 1400; there is no record of the precise date or the circumstances of his demise, despite vivid and colourful speculation. Bernard O'Donoghue is one of the country's leading poets and medievalists. His accessible new selection includes a linking commentary on the chosen texts, together with a comprehensive line-for-line glossary that makes this the most approachable and accessible introduction to Chaucer that readers can buy.

Faber has a poetry list worth bragging about. What other publisher could conjuure up a series like this? Some of the strongest names in contemporary British poetry compile and introduce selections from favourit poets of the past

Given how little we know about the lives of any of his predecessors in English poetry, it is remarkable how much we do know about Chaucer. He grew up in London and lived there all his life, apart from professional trips to France, Spain, Italy and to other parts of England. His family was well off: his grandfather was a wine merchant from Ipswich who moved to London to set up the business into which his son, Geoffrey’s father, succeeded him. Little is known about the education of the poet, who was an only child; despite the impressive erudition and love of learning evident throughout his writings, he seems not to have gone to university. He was a prominent courtier and civil servant, starting out in his early teens as a page in the service of the Countess of Ulster, and by 1360 serving in the retinue of her husband Lionel Duke of Clarence in a bloody period during the Hundred Years War in France. He was captured at a battle near Rheims, and ransomed, the tradition is, by the king, Edward III. In 1367 he married Philippa de Roet, the daughter of a Flemish knight and probably the sister of Katherine Swynford, the mistress and ultimately third wife of Edward III’s powerful and dictatorial son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. It was the connections with Gaunt in particular that kept Chaucer prominent in public affairs.

Though Chaucer probably translated parts of Le Roman de la Rose (the Middle English verse version, The Romaunt of the Rose, which is half-heartedly included at the end of all modern editions of Chaucer, is possibly his) and wrote short poems in French and English in the 1360s, his first major poem was The Book of the Duchess, probably written as an elegy for the death of Gaunt’s first wife Blanche (the mother of Henry IV) in 1368. Thereafter Chaucer was an active public servant and writer, though the sequence of events is not always clear. It is possible, though the evidence is not wholly conclusive, that Chaucer travelled to Italy and Ireland in Lionel’s entourage. He certainly visited Genoa on trade missions in 1372 and 1373. The public and literary activities sometimes coincided: for example, it was probably on a diplomatic trip to Lombardy that he encountered the works of Boccaccio, at least two of which he drew on for major works, The Knight’s Tale and Troilus and Criseyde. His roles in public life were significant: he was a Justice of the Peace, and in 1386 a Knight of the Shire for Kent, in which capacity he was a member of the ‘Wonderful Parliament’ in October and November 1386 which marked an important escalation of the hostilities between the young king and parliament. In the mid-1380s he composed Troilus and Criseyde, and he was engaged on his most famous work, The Canterbury Tales, from the late 1380s until his death in 1400. There is no record of the date or circumstances of his death, despite the amusing and lurid speculations in Terry Jones’s whodunnit Who Murdered Chaucer? A Medieval Mystery (2003).

The first striking quality of Chaucer’s writing is its capacity to express general truths. We immediately recognise the world he creates. This is not the quality that our era most prizes in poetry though. In his first ‘Milton’ essay, T. S. Eliot criticises the imagery of ‘L’Allegro’ and ‘Il Penseroso’ for being ‘all general’. He objects to the lines about the ploughman ‘who whistles o’er the furrowed land’ and the milkmaid who ‘singeth blithe’ that ‘it is not a particular ploughman, milkmaid and shepherd … (as Wordsworth might see them)’, but an aural effect ‘joined to the concepts of ploughman, milkmaid, and shepherd’. On these principles, he would not like Chaucer (and indeed Eliot, unlike Ezra Pound who said that ‘Chaucer had a deeper knowledge of life than Shakespeare’, has little to say about him). When he is most serious, Chaucer, of whom Dryden in the preface to his Fables concluded ‘here is God’s plenty’, has a penchant for the general truth and the perfect cameo to represent it: ‘the smylere with the knyf under the cloke’ amongst the horrific depictions on the walls of the Temple of Mars in The Knight’s Tale; the plight of Criseyde ‘with women fewe among the Grekis stronge’; the insights about writing in the introduction to his classical dream-poem The Legend of Good Women:

books had been lost And yf that olde bokes were aweye

Lost Yloren were of remembraunce the keye.

This kind of generalising power is not what we have looked for in poetry since Eliot and the modernists. Chaucer shares with Dickens and Jane Austen the capacity to create a character – or caricature – with a telling stroke of the pen: the Medical Doctor on the Canterbury pilgrimage who ‘knew the cause of every malady’ and, recognising that ‘gold in physic is a cordial, therefore … lovede gold in special’. Nowhere was there anyone as busy as the Lawyer on the pilgrimage: ‘and yet he semed bisier than he was.’ We recognise these vocational clichés, and admire the mot juste in their expression.

Chaucer is of course a great entertainer, as everyone knows. As well as generalities, there are cameos of more particular wit and astuteness: the presumptuous monk in The Friar’s Tale who takes over the house he visits, ‘and fro the bench he drove away the cat’; the exuberance of The Miller’s Tale in Alysoun’s exclamation after she has pulled in from the window ‘hir naked ers’:

‘Tehee!’ quod she, and clapte the wyndow to.

As an entertaining presence, the Wife of Bath manifests both tendencies, enlivening her general traits – mostly the stereotypical details of the shrewish wife – with vivid verbal details, addressing one of her wretched husbands as ‘old barrelful of lies’ and bursting out with the great lament –

Allas, Allas! That evere love was synne!

Yet none of this – generalising power or sparkling verbal cameos – would establish Chaucer as one of the greatest poets in English. He would still be open to the reservation which Matthew Arnold appended to his admiration of him: that he lacks ‘high seriousness’, one of ‘the grand virtues of poetry’. But something else, less obvious and less generally noticed, does make Chaucer’s poetic gift extraordinary. In a few brilliant pages of Seven Types of Ambiguity William Empson anatomises an extract from Troilus and Criseyde, showing that it has the same verbal density and ironies of language as the most accomplished lyric. Empson states the problem for the narrative poet acutely, illustrating in passing perhaps why our era is unreceptive to the long poem. ‘In a long narrative poem the stress on particular phrases must be slight, most of the lines do not expect more attention than you would give to phrases of a novel when reading it aloud; you would not look for the same concentration of imagery as in a lyric. On the other hand, a long poem accumulates imagery.’

But Empson goes on to show how Chaucer’s poetry, as well as accumulating a sustained imagery, does respond remarkably well to the kind of attention you would give to a lyric. Let me give a few examples (most from texts which are included in this selection) of Chaucer’s skill with imagery, from the work that stands with Troilus and Criseyde as his greatest: The Canterbury Tales. The first is the most bizarre episode in the whole journey to Canterbury: the extraordinary appearance of the Canon and his Yeoman. If Chaucer had seriously planned to complete the ambitious programme of the Tales – to write four stories each for thirty-odd pilgrims – he hardly helped his cause by introducing two more characters, the mysterious Canon and his attendant Yeoman, a few miles from the end of the pilgrimage. Would this require eight more tales? The episode begins with one of Chaucer’s memorably exuberant lines: as the fat Canon comes galloping on a hot day to catch up with the pilgrims, he is sweating ‘that it wonder was to see’; he (or possibly his horse) is so flecked with sweaty foam that he looks as two-toned as a magpie:

But it was joye for to seen hym swete!

So far so amusing! But this Canon is a very strange figure: an alchemist as it turns out (anticipating the comedy of Ben Jonson: a dramatist whose work Chaucer’s resembles in the mixture of the general and the particular I have been noting). In the first 26 lines of the Canon’s Yeoman’s Prologue, sweat is mentioned four times and the foam of sweat twice. The Canon’s forehead, we are told, drips like ‘a stillatorie’ – a vessel or room for distillation. In short, this alchemist is presented as a personified still. And when the Canon overhears what his Yeoman is going to talk about, ‘he fledde awey for verray sorwe and shame’ and we hear no more about him. He is as evanescent as the Cheshire Cat – as deliquescent as the materials of his absurd and sinister art. The story that follows, The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale, is an account of the machinations of the alchemists, sustained and held together by a language drenched with liquid and sublimation: the ‘spirites ascencioun’ from the pot and glasses, the urinals and descensories, waters rubifying and bulls’ gall, water’s albification, dung and piss and imbibing, fermentation and corrosive waters. Throughout the description the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.8.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Lyrik / Gedichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Canterbury Tales • Medieval • The Canterbury tales • Troilus and Criseyde • wife of bath |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-31496-1 / 0571314961 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-31496-6 / 9780571314966 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 254 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich