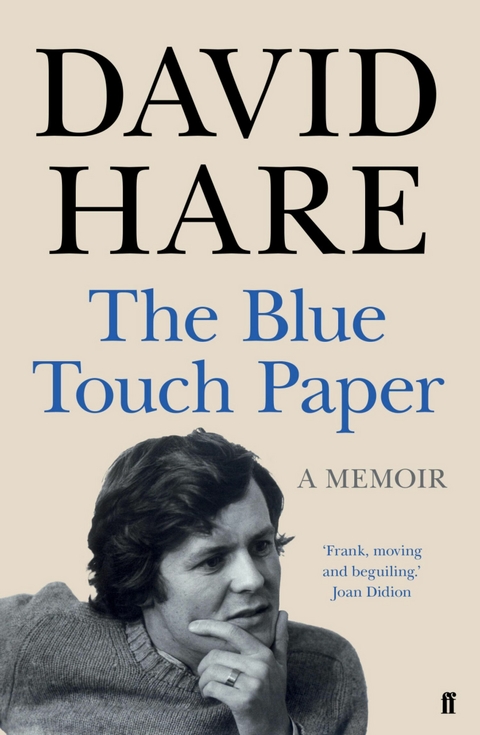

Blue Touch Paper (eBook)

384 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-29435-0 (ISBN)

David Hare has written over thirty stage plays and thirty screenplays for film and television. The plays include Plenty, Pravda (with Howard Brenton), The Secret Rapture, Racing Demon, Skylight, Amy's View, The Blue Room, Via Dolorosa, Stuff Happens, The Absence of War, The Judas Kiss, The Red Barn, The Moderate Soprano, I'm Not Running and Beat the Devil. For cinema, he has written The Hours, The Reader, Damage, Denial, Wetherby and The White Crow among others, while his television films include Licking Hitler, the Worricker Trilogy, Collateral and Roadkill. In a millennial poll of the greatest plays of the twentieth century, five of the top hundred were his.

When, in 2000, the National Theatre published its poll of the hundred best plays of the 20th century, David Hare had written five of them. Yet he was born in 1947 into an anonymous suburban street in Hastings. It is a world he believes to be as completely vanished as Victorian England. Now in his first panoramic work of memoir, ending as Margaret Thatcher comes to power in 1979, David Hare describes his childhood, his Anglo-Catholic education and his painful apprenticeship to the trade of dramatist. He sets the progress of his own life against the history of a time in which faith in hierarchy, deference, religion, the empire and finally politics all withered away. Only belief in private virtue remains. In his customarily dazzling prose and with great warmth and humour, David Hare explores how so radical a shift could have occurred, and how it is reflected in his own lifelong engagement with two disparate art forms - film and theatre. In The Blue Touch Paper David Hare describes a life of trial and error: both how he became a writer and the high price he and those around him paid for that decision.

David Hare is the author of 30 full-length plays for the stage, seventeen of which have been presented at the National Theatre. They include Racing Demon, Skylight, Amy's View, The Blue Room and Stuff Happens. His many screenplays for film and television include The Hours, The Reader, Page Eight, Turks & Caicos and Salting the Battlefield.

When I was growing up nothing excited me more than getting lost. Walking bored me when I knew the way. Until I was twenty-one, my home was on the south coast, firstly in a modest flat up a hill in St Leonards, later in a semi-detached in Bexhill. But when we made our annual family trip to my maternal grandmother’s in Paisley, my sport was to get on a bus, close my eyes and then get out. I was barely ten and I had no idea where I was. Sometimes I recognised Love Street, the home of the local football club, St Mirren, for whom my uncle Jimmy was a talent scout, but nothing else made sense to me. My grandmother Euphemia was furious when I got back two hours late for tea – in those days ham, lettuce, tomato and pork pie, followed by a lot of biscuits and cakes. This after a lunch of mince and tatties.

When I disappeared, nobody seemed overly concerned. Children vanished from time to time, that’s what happened. A lower-middle-class childhood on the south coast of England in the 1950s became a distinctive mixture of freedom and repression. It was because children were encouraged to make their own way home from school that my nine-year-old friend Michael Richford and I encountered our first sex offender on the Downs, right next to the air-raid shelter which no one had bothered to demolish. The spectral predator was moustached, wearing a grey overcoat and a grey scarf. Our refusal to show him our penises did not seem to lessen his pleasure in showing us his. We two boys hurried home, through the abundant nettles and brambles, up our separate back paths and past the hen-houses that lingered on beneath hedges at the ends of gardens for so many years after the war. Later we were taken by police to line-ups and asked, unsuccessfully, to identify various old men coming out of the Playhouse Cinema after a smoky matinee of The Dam Busters. But, in spite of all the dark parental huddles which followed on the incident, I was still allowed at thirteen to go on my own by train to London. Why? At fifteen I was hitch-hiking across England to Stratford in the hope of seeing Vanessa Redgrave in The Taming of the Shrew. At seventeen, I left for America. My mother wished me good luck, and no doubt she fretted, but at no point did she try to stop me. I was free. Later I read Nietzsche: ‘All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking.’

Over the years I was to convince myself I’d had an unhappy childhood, though I would never have dared say so in public while my parents were alive. Even writing these words causes me a flush of shame. The very over-sensitivity which equips you to be a writer also makes being a writer agony. But in retrospect it’s extraordinary how much licence my mother allowed to my sister and me. It goes without saying that after the Second World War, when dealing with their children, adults almost never stooped to our level. Down where we were, we looked up at all times. There was none of today’s dippy celebration of children as little unfallen gods. We were not pushed self-importantly through the streets in thousand-pound chariots, scooping up croissants and ice creams on the way. Nobody told us we were wonderful. But on the other hand, even in the stifling atmosphere of suburbia, among those rows of silent, russet-bricked houses and identically tended lawns, adorned with billowing washing lines, strawberry plants, runner beans and raspberry canes, we were granted a level of independence which now seems unimaginable.

Or was that simply because of my mother? Nancy Hare, as she came to be known, had been born Agnes Cockburn Gilmour just a decade into the twentieth century, and brought up as the middle child of three by fiercely puritanical parents who did their best to force upon her a poor opinion of herself. The result, in her mid-twenties, had been a nervous breakdown, precipitated perhaps by the feeling that she was never going to find a husband. She was tall, striking rather than beautiful, with looks which seem typical of their period. Her only escape from what we would now call low self-esteem was her flair for amateur dramatics. She had a good voice and a prized diploma in elocution. The family business was road haulage. Even in my youth, the men stood at lecterns and horses were maintained in stables and sent out on the roads, admittedly as a sort of tribute to past practices, but maintained nevertheless. My grandparents had been the first people in Paisley to own a car, but if that implied prosperity, then letting it show in any way beyond the motor-mechanical would have been frowned on, the subject of ceaseless comment from neighbours never reluctant to pass damning comments on each other. The family religion was judgement.

My mother had been raised in Whitehaugh Drive, a cheerless, rising street of Victorian stone houses, blackened by industry and with back yards the size of handkerchiefs. A few doors up was the spinster Betty Richie, who, on its release, was to see The Sound of Music 365 times, once for every successive day of the year. The strong-minded Euphemia had done her very best to make sure that my uncle Jimmy stayed unmarried as long as possible, the better, she hoped, to look after her in her old age. When Jimmy did, at forty, eventually make it out of the house with the inoffensive but marginally vulgar Nan, a childless spinster who bestowed sweet tea, jam and honeyed flapjacks down the throat of any child who came near, his mother refused to allow that the marriage had happened or to admit Aunt Nan to the family house. Only the favoured Peggy, the youngest and brightest of the three children, was lined up to make a brilliant match, and even allowed to go off from Paisley Grammar School to Glasgow University, where she at once fell in love with a medical student who also shone as a rugby player. For my mother, to whom the drunken, violent pavements of Paisley were nightly torture, a fate like Betty Richie’s seemed to await.

For the whole of her life my mother was scared. She managed to be scared for forty years in Bexhill-on-Sea, a Sussex dormitory for the retired and soon-to-be-retired which is not, on the surface at least, the scariest of places. I both inherited her fear and tried to reject it. Her mother left Nancy with a strong idea of how things should be done. I only once saw her in any kind of trouser. Respectable women wore skirts. No incident loomed larger in her later anecdotal life than the time when, during the war, while working for the Wrens, she mistakenly drank a china cup of whisky late at night in the belief that it was tea. She made the resulting wreckage of her consciousness in the early hours sound like a descent into un-merry hell. Her horror of alcohol, of men, of violence and of any kind of public disorder seemed to me in my equal primness like a horror of life. My mother was always on guard, always on watch, expecting men, children, neighbours, strangers, and, I’m afraid, her own family to betray signs of their underlying beastliness. Civilisation was a veneer, a pleasant veneer, yes, but not to be trusted. Essential things always came out. I grew used to her favourite rebuke. ‘I love you,’ she’d say to me. ‘But I don’t like you.’

Nancy was an intelligent and sensitive woman, born, by bad luck, into the wrong place at the wrong time. She passed her days as a secretary, or as she herself preferred to call it, a shorthand typist, at Coats, the cotton firm, where sometimes, among the reels and bobbins, she wondered whether she belonged with the professional actors like Duncan Macrae who would come from the Citizens’ Theatre to Paisley to guest-star in otherwise amateur productions of thrillers and James Bridie’s romances. Macrae was an expert in what the Scots of the time called glaikit comedy. We would call it gormless. But if a working-class satellite of Glasgow was not easy for her, then nor, I think, was the suffocating gentility of the south coast of England to which my father transported her after the war. They had met at a dance in Greenock in 1941, and the progress of their mysterious courtship was recorded by my aunt Peggy. In her diary, for reasons not clear to me or to my sister Margaret, Peggy sometimes calls my mother Agatha, even though that was neither her given nor her adopted name.

27 September 1941

My beloved sister went off at 10 o’clock this morning and didn’t get back till the minutes before midnight. She was very gay when she came in and announced that she was bringing an Officer for lunch on the morrow. Shrieks from mother.

28 September 1941

Clifford came. He was most charming and an easy talker; he was obviously very fond of Agatha, kept turning round and beaming at her in such an adoring way. Agatha dashed into the back kitchen between courses and asked me what I thought of him. I gave my hearty approval. I think she could do a lot worse, especially at her age. Admittedly, he’s queer looking and smaller than she is, but he’s kindness itself and very generous.

9 October 1941

Bombshell arrived today at lunch-time. Nancy’s letter for this week brought the news that she was going to marry Clifford quite soon. Mother was bowled over by the news and called me all sorts of names for not letting her know sooner. Clifford is coming to see Father at the weekend and Dad is going to ask him gravely if he thinks he can keep her. It’s going to be killing.

13 October 1941

Again an ominous date. Clifford arrived tonight to explain his financial position to Father. Then we had some supper and everything seemed to be flowing smoothly until the date was...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.8.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | 3 day week • David Hare • Dominic Sandbrook • National Theatre • Nicole Fahri • Nicole Farhi • Peter Hall • Royal Court |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-29435-9 / 0571294359 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-29435-0 / 9780571294350 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich