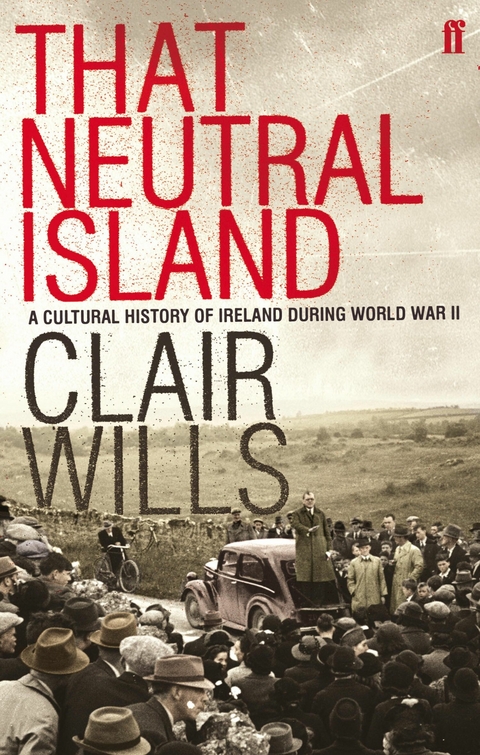

That Neutral Island (eBook)

512 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-31739-4 (ISBN)

Clair Wills is Professor of Irish Literature at Queen Mary, University of London. Her previous books include a study of Paul Muldoon. She is an editor of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature.

Of the countries that remained neutral during the Second World War, none was more controversial than Ireland, with accusations of betrayal and hypocrisy poisoning the media. Whereas previous histories of Ireland in the war years have focused on high politics, That Neutral Island brings to life the atmosphere of a country forced to live under rationing, heavy censorship and the threat of invasion. It unearths the motivations of those thousands who left Ireland to fight in the British forces and shows how ordinary people tried to make sense of the Nazi threat through the lens of antagonism towards Britain.

[A] fascinating and unusual snapshot of life in the war years.

I grew up with stories of the Second World War that stemmed from very different experiences. My mother lived the war years – her early teenage years – on a small farm in West Cork. In 1934 my grandfather, an agricultural labourer, inherited £300 from an older brother who had emigrated to Chicago some fifty years earlier, where he had done well out of a livery stable. With the money my grandfather bought the house and the thirty-acre farm, previously a tenant-holding on a once large estate, and now ‘in fee’ to the Land Commission. The family’s new, if tenuous, prosperity matched the hopes of the new Ireland of the 1930s. The nationalist Fianna Fáil party, which came to power in 1932, was bent on gaining greater political and economic independence from Britain. Along with this went economic independence for Irish citizens, and in particular for the small farmer. The thirty-acre farm – thought large enough to maintain a family on the produce and its proceeds – was the model on which Fianna Fáil hoped to build a new, fair, if frugal, agrarian society. My grandparents’ large family subsisted, in pretty typical style, as far as possible on their own crops and the small income from the sale of milk, eggs and pigs, boosted by the older children’s earnings. For the boys there was rabbit snaring and seasonal agricultural work for the County Council, on jobs such as ditch clearing and drainage; for the girls, domestic service in the home of the local Minister. Except for the unaccountable fact that my grandfather had been born a Protestant (though he had long since converted), the family came close to embodying the ideal of a self-sufficient, rural, devout and independent Ireland.

Powered by a sense of duty to such people, and to the needs of a young and relatively weak state, the Fianna Fáil leader, Eamon de Valera, was determined to keep Ireland out of the war that, by the mid-1930s, was already looming. Disillusioned with the politics of collective security after the failure of the League of Nations, and convinced of the democratic right of small nations to protect themselves from becoming embroiled in the conflicts of the big powers, he was also committed to neutrality for wholly pragmatic reasons. Ireland had a small, ill-equipped army, and few defences. Still only in its second decade of independence, it was a vulnerable state, which could all too easily be swallowed up in a widespread war. The world of the small farmer and the small town, which lay at the heart of de Valera’s vision of an independent Ireland, would go with it. In the late 1930s de Valera worked to regain control of Irish defences, bartering for the return, in 1938, of all naval and air facilities still in British hands. And on 3 September 1939, as Britain and France declared war on Germany, the Irish government sealed its commitment to neutrality, passing an Emergency Powers Act, which remained in force until 2 September 1946. Throughout the war years Ireland’s Taoiseach resisted Churchill’s – and later Roosevelt’s – attempts to encourage, persuade and occasionally bully him into the war; supported by the vast majority of the Irish population, de Valera resolutely kept Ireland out of the conflict.

My mother’s principal memories of the Emergency are of shortages, particularly of sugar, tea and flour; of trains on the Skibbereen–Schull Light Railway (‘the tram’) running so slowly on inferior fuel that you could climb on and off them as they went uphill; of visits to a pair of relatively well-off elderly Protestant neighbours who owned a working radio; and of making up stories of British successes in the Battle of Britain to tell to her father when she returned home – news of British losses was sure to put him in a bad mood. As a schoolgirl her day-to-day lessons, friendships, and fraught relationships with the nuns were no doubt more present to her than the far-off events of the world war. In addition there were domestic chores and jobs on the farm such as drawing water, collecting eggs, feeding the sow and the hens, making butter, going to the creamery. By the blueish light of the paraffin lamp, and sometimes by candlelight, she would reread the stories in the rare copies of Ireland’s Own, books borrowed from the school ‘library’, and the dog-eared romance novels passed from hand to hand. She attended vocational classes in domestic economy organised by the parish priest, where – despite the shortages – she learnt fancy techniques such as how to make pastry by rubbing the butter into the flour, or how to beat egg whites so stiff you could turn the bowl upside down over your head. Yet elaborate baking at home was impossible; in common with nearly all the other homes nearby, all cooking on the farm was done in the ‘bastable’ over an open fire.

For her older siblings there were occasional visits to the cinema in the town, more frequent music sessions in neighbours’ homes, card-playing, Sunday-night patterns, turkey-drives, fair days, dances in the town hall and a round of social activities centred on the local parish church. In many ways, the war years for my mother’s family were a continuation of life in the 1930s, with its local focus, its seasonal liturgical ritual, as well as its economic privations. Frugality was the order of the day, and worries about the supply of day-to-day necessities took priority over the seemingly distant war. Even had my mother been interested in the global news she would have found it difficult to follow events. Early on in the war the family’s radio became inoperable, due to the difficulty of recharging the wet and dry batteries. They lived too far from the town for daily purchase of a newspaper, and in any event transport difficulties often delayed or cancelled delivery of the Cork Examiner to the smaller market towns. The local weekly paper was true to its type, carrying almost exclusively local news, along with frequent government directives on emergency measures.

My future father, meanwhile, was living out the ‘typical’ wartime experience of an English youth on the outskirts of London – including evacuation to Wales in the early part of the war. Since his father, a hospital clerk, was too old to be conscripted, and he himself was too young (he turned sixteen in the summer of 1945), the family avoided the fears and dangers common to those in the Forces, or with relatives in the Forces (an older brother went into a reserved occupation). But in the row of terraced houses owned by the hospital, in which the family lodged, neighbours received news of the death of relatives. For months at a time the family slept each night in the Anderson shelter in the garden, later migrating to the Morrison shelter under the kitchen table. Towards the end of the war they bedded down in a huge complex of tunnels built into a hill in the grounds of the hospital. Planes from the air force base at Kenley Aerodrome flew low over his school on the South Downs each day, and everywhere there was evidence – in bomb damage, troop movements, defence emplacements – of a country wholly given over to the war effort.

Life on the British home front was undoubtedly more disrupted and perilous than life in neutral Ireland, but it was also more varied. There were weekly visits to the local British Restaurant for dried egg and chips, in order to eke out the rations, and later youth clubs and dances. As a youngster my father read the Beano and the Dandy, worked his way through the adventure stories in the local library, collected models of the planes droning overhead, listened to music and comedy on the wireless. The technology that made the war so lethal also gave him more freedom – as he cadged the occasional ride on the back of a motorbike out into the country, or took the bus every Saturday morning (and later every Saturday night) to the Regal cinema to watch the latest films and Pathé newsreels.

On the face of it, it would be hard to come up with two more contrasting experiences of the war. On the one hand, life in a culture increasingly driven by technology and the beginnings of mass consumption, on the other, a rural life that was still almost pre-machine-age: the contrast seems emblematic of the distinction between living inside and outside the war. Many Irish people volunteered for the British forces, out of conviction, economic necessity, or a youthful thirst for adventure. Others, attracted by the prospect of a job with decent wages, moved to England to work in the war industries. But for the majority of the Irish population who stayed at home, the conflict was distant from their own concerns.

Yet the state of economic siege, the breakdown of transport, the sense of isolation, had more than simply material effects. As one journalist, a schoolboy during the Emergency, recalled, ‘apart from the food, fuel and petrol rationing and other inevitable discomforts or deprivations, the atmosphere of fear, menace and foreboding was constant and almost tangible. Quite simply, one just could not shut it out, at least for long.’ As the Irish government was keen to emphasise, neutrality was not peace. While the violence of the conflict may have seemed remote to most people, everyday life in Ireland was shaped by the hardships, constraints, and psychological pressures of surviving in a war-torn world. Indeed, the very fact that my parents’ lives could converge at the end of the decade speaks of a shared sensibility. Like thousands of other Irish girls, at war’s end my mother applied to train as a nurse in the newly formed National Health Service. In seeking a future abroad, she was typical of the thousands who left Ireland in the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.4.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | conflict • Independence • Military • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-31739-1 / 0571317391 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-31739-4 / 9780571317394 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich