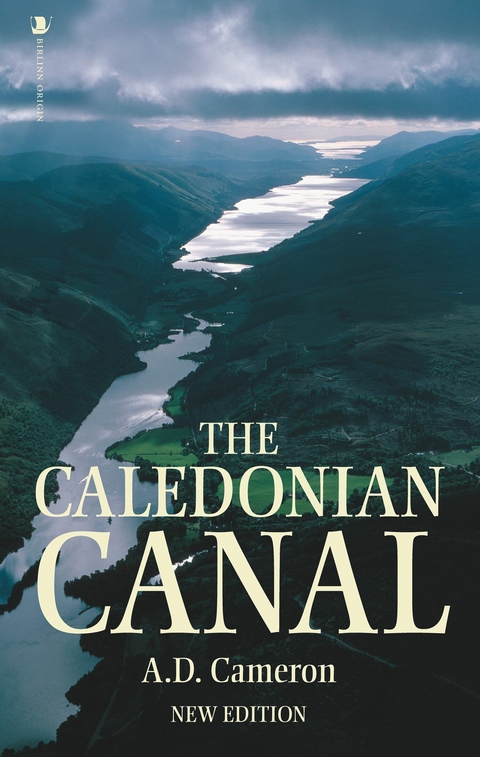

Caledonian Canal (eBook)

236 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-0-85790-953-4 (ISBN)

A.D. (Sandy) Cameron is a retired schoolteacher and lives in Portobello.

Telford's plan, to connect Loch Ness, Loch Oich and Loch Lochy with each other and the sea, was a huge undertaking which brought civil engineering to the Highlands on a heroic scale. Deep in the Highlands, far from the canal network of England, engineers forged their way through the Great Glen to construct the biggest canal of its day: twenty-two miles of artificial cutting and no fewer than twenty-eight locks. A.D. (Sandy) Cameron's book has long been recognised as the authoritative work on the canal as well as a reliable and useful guide to the surrounding area. There are intriguing old plans, not discovered until 1992, and a survey of the dramatic rise in pleasure-craft traffic during the last two decades. But the highlight of the recent past was undoubtedly the Tall Ships passing through the canal in stately procession in 1991. Impossible, then, not to feel the fascination of this beautiful waterway: a working piece of industrial history and a remarkable engineering achievement. This book is a fitting celebration of this remarkable feat of engineering.

A.D. (Sandy) Cameron is a retired schoolteacher and lives in Portobello.

2

WHY BUILD A CANAL IN THE GREAT GLEN?

In a mountainous country with an indented coastline like Scotland, people had used the sea from the earliest times as the easiest means of communication. Most settlements were coastal and lines of penetration inland took advantage of firths and long sea lochs. The wealth of Bronze Age remains in the Great Glen, for example, shows that it attracted very early settlers, using river and loch to make their way inland and gain access to the east coast. Later, in the Middle Ages, most burghs in the Lowlands were created within the sound of the sea and traded with Europe and one another by sea. The Highlands, however, remained almost destitute of towns.

When the transport revolution came in England in the 1750s it started with the construction of canals to transport heavy goods like coal to the rising industrial towns. James Brindley’s canal from inside the coal mine at Worsley to Manchester set the pattern. Direct delivery in bulk from an inland mine to an inland destination proved that inventiveness and hard work could cut costs and helped to make the Industrial Revolution possible. During the sixty years of the reign of George III the navigable stretches of English rivers were joined with one another by canals until Manchester was linked with London, and Gloucester, if need be, with Hull. Inland waterways became the arteries of trade, financed by private enterprise and cut by navigators, later called ‘navvies’. Scotland, too, saw the construction of canals during this Canal Age.

The first project to be surveyed in Scotland was for a sea-to-sea canal across her narrow waist between the Forth and the Clyde. The second, the Monkland Canal, between Airdrie and Glasgow, was simply an artificial ditch dug with the aim of undercutting the coal prices charged by local mine-owners nearer to Glasgow. Work was going forward on both by 1770 and it was not surprising that thoughts were turning towards the prospect of cutting canals in many other parts of the country, even in the Highlands.

This is an example of how ideas for the improvement of a region at any time tend to follow current fashion. Projects which have proved successful earlier elsewhere are taken up and advocated with enthusiasm even where conditions are less favourable or, frankly, unfavourable. It was happening with estate improvement in the eighteenth century: the high returns received by improvers like Coke of Holkham in Norfolk were an incentive to others, but not something that was always achieved. It was happening with the foundation of factory villages, such as Stanley in Perthshire and Spinningdale in Sutherland, which had to compete with much larger units of production in Lancashire and Lanarkshire. It was to happen again much later with a proposal for a railway to Skye and the abortive railway between Spean Bridge and Fort Augustus which ran with few passengers along the south-western half of the Great Glen from 1903 to 1933 and was described by John Thomas in The West Highland Railway as ‘the classic example of the railway which should not have been built’.

At the time the cry everywhere was for canals and the Great Glen running from south-west to north-east from Fort William to Inverness looked as if it had been shaped by nature to make the canal-builder’s job easy. Where else in mountainous country in Britain was there a stretch of sixty miles involving a rise above sea level of only about a hundred feet? Which other area contained three long narrow lochs in a straight line capable of forming two-thirds of the waterway without human effort? Where else was there such heavy rainfall to swell the mountain streams and keep the water level high? What loch could compare with Loch Ness in length (22 miles) or in depth (129 fathoms), deeper than any part of the North Sea between Scotland and Denmark? The location was attractive and the prospect of a great navigation there to join the Atlantic with the North Sea was to many observers an intriguing possibility.

Fishing boats in full sail by the back of Tomnahurich: the Brahan Seer’s prophecy fulfilled.

Even in the seventeenth century the best-known Highland prophet, the Brahan Seer, predicted: ‘strange as it may seem to you this day, the time will come, and it is not far off, when full-rigged ships will be seen sailing eastward and westward by the back of Tomnahurich [inland] at Inverness’.

Old field patterns in Glen Roy with pastures beyond, typical of former ways of farming in the Great Glen.

The Corrieyairack, the greatest of General Wade’s military roads, from the Great Glen near Fort Augustus over towards Dalwhinnie, built in 1731 and being restored in 1992.

Cattle in Glen Nevis.

Serious proposals for canals in the Highlands, however, were not put forward simply to fulfil a prophecy or because a site looked promising. They were considered rather in the context of what might be called the Highland problem after the Jacobite debacle at Culloden in 1746.

Following ‘the harrying of the glens’ and the people in them by Cumberland’s Redcoats, the Government treated the Highlanders with studied repression. New laws forbade them to carry weapons, wear tartan or even play the bagpipes. In 1747 every chief lost his hereditary power to judge and punish members of his own clan and the estates of those chiefs who had supported the Jacobite cause were forfeited to the Crown and run by Commissioners. Government troops occupied the forts along the Great Glen and elsewhere, and the programme of building military roads, which General Wade started in 1721, was extended. These were all negative measures, aimed at preventing another rising or rebellion. But there was positive thinking too, shown best and earliest in the way the forfeited estates were administered.

Schemes of agricultural improvement and tree-planting were undertaken. Crafts for young people such as carpentry for boys and spinning for girls were encouraged and spinning wheels were provided. With the co-operation of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge, more schools were built, where children could learn to read and write English, although later the Society produced a Gaelic Bible. These were some of the ways in which the Commissioners tried to bring those areas of the Highlands for which they were responsible more into line with the rest of Britain. Theirs was the first attempt ‘to do something about the Highlands’, but their critics viewed their efforts as a campaign to anglicise the Highlanders and destroy a rich indigenous culture.

Broadly the Highlanders had differed from people further south in two main ways – their social organisation and their subsistence economy. The social structure had been based on the clan, subject to the absolute authority of the chief, held together by kinship and loyalty and designed to provide him with the greatest number of warriors. Between the chief and the tenants stood the tacksmen, who were usually his close relations and who held land from him on ‘tack’ or lease, at a low rent and lived off the rents and services paid to them by their tenants in return for their patches of land. The tacksmen might not be rich by southern standards but they were gentlemen, the chief’s deputies in their areas and responsible for raising their tenants as fighting men. The Highland chiefs were the only men in Britain capable of raising an armed force spontaneously, as they did in the Rising of 1745. Admittedly clanship was decaying in parts of the Highlands before this time and clan feuds had become uncommon but even after the abolition of the Heritable Jurisdictions in 1747, old ways and old loyalties persisted. An ancient social structure does not disappear at the stroke of a lawyer’s pen.

Clan society was supported by a primitive subsistence economy, part arable but mainly pastoral, devoted to keeping cattle as well as a few sheep and goats. The surplus cattle were sold or driven south along the drove roads to the cattle trysts of Crieff or Falkirk. The price they fetched paid the rent: there was usually little left over. Highland agricultural methods served to provide a fairly high population with their basic needs in relative poverty. Years of crop failure brought hunger and death, but the introduction of the potato crop proved a life-saver in the Highlands. Not only did it provide an alternative food when grain crops failed, but it yielded a greater amount of food than the same area under grain. It was probably a major factor in keeping more people alive in the Highlands and consequently in supporting the startling rise in population in the later years of the eighteenth century.

Recording a rise of 40,000 in the forty-six years to 1801 in the Highland and Island counties – Argyll, Inverness, Ross and Cromarty, Sutherland, Caithness, Orkney and Shetland – the figures do not reveal the full extent of the increase because they do not take into account the substantial losses through emigration. Between 1768 and 1800 at least 20,000 people left the Highlands for the colonies in America alone, not counting those who had gone south in search of work.

Before the ’45, a clan chief’s power and position depended on the number of fighting men he could muster. In the pacified Highlands after it, having a large number of tenants was becoming an embarrassment to him as he ceased to be a chief and became a landlord. Consequently, tacksmen no longer deserved their privileged position. Since cattle were increasing in value there was a strong case for a landlord specialising in cattle-rearing himself or encouraging some of his tenants to do so in return for higher rents. Some tacksmen...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Schiffe |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Naturführer | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Technik ► Bauwesen | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Architecture • Canal • canal network • Civil Engineering • engineers • England • Great Glen • Guide • Highlands • Industrial History • Loch Lochy • Loch Ness • Loch Oich • Scotland • Social History • Tall Ships • Thomas Telford • waterway |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85790-953-3 / 0857909533 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85790-953-4 / 9780857909534 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 37,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich