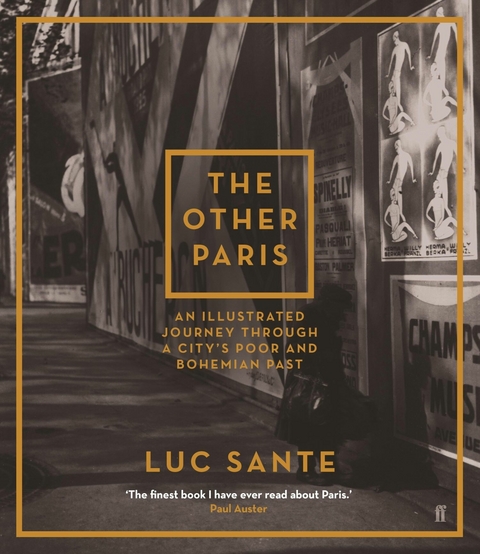

Other Paris (eBook)

352 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-32587-0 (ISBN)

Luc Sante was born in Verviers, Belgium. His other books include Low Life: Lures and Snares in Old New York, Evidence, The Factory of Facts, and Kill All Your Darlings. He is the recipient of a Whiting Writers Award, an Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Grammy (for album notes), an Infinity Award for Writing from the International Center of Photography, and Guggenheim and Cullman fellowships. He has contributed to the New York Review of Books since 1981, and has written for many other magazines. He is Visiting Professor of Writing and the History of Photography at Bard College and lives in Ulster County, New York.

Paris, the City of Light. We think of it as the city of the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre, of white facades, discreet traffic and well-mannered exchanges. But there was another Paris, hidden from view and virtually extinct today - the Paris of the working and criminal classes that shaped the city over the past two centuries. In the voices of Balzac and Hugo, assorted boulevardiers, barflies, rabble-rousers and tramps, Sante takes the reader on a vividjourney through the seamy underside of Paris: the improvised accommodations of the original bohemians; the flea markets, the rubbish tips, and the hovels. The Other Paris is a lively tour of labour conditions, prostitution, drinking, crime, and popular entertainment, of the reporters, realiste singers, pamphleteers, serial novelists, and poets who chronicled their evolution. It upends the story of the French capital, reclaiming the city from the bon vivants and the speculators, and lighting a candle to the works and days of the forgotten poor.

lt;b>Luc Sante was born in Verviers, Belgium. His other books include Low Life: Lures and Snares in Old New York, Evidence, The Factory of Facts, and Kill All Your Darlings. He has contributed to the New York Review of Books since 1981, and has written for many other magazines. He is Visiting Professor of Writing and the History of Photography at Bard College and lives in Ulster County, New York.

Paris is sufficiently compact that you can cross it with ease, in a few hours, and it has no grid, forestalling monotony. It virtually demands that you walk its length and breadth; once you get started it’s hard to stop. As you stride along you are not merely a pedestrian in a city—you are a reader negotiating a vast text spanning centuries and the traces of a billion hands, and like a narrative it pulls you along, continually luring you with the mystery of the next corner.

The frontispiece, by Célestin Nanteuil, for Les rues de Paris (G. Kugelmann, 1844)

Paris contains some 3,195 streets, 330 passages (a term that encompasses both arcades and alleys), 314 avenues, 293 impasses, 189 villas (an enclosed mansion, or a grouping of houses not unlike a mews), 142 cités (a contained development, sometimes carefully designed and sometimes a slum), 139 squares, 108 boulevards, 64 courts, 52 quays, 30 bridges, 27 ports, 22 galeries (arcades), 13 allées, 7 hameaux (literally “hamlets”), 7 lanes, 7 paths, 5 ways, 5 peristyles, 5 roundabouts, 3 courses, three sentes (another variation on “path” or “way”), 2 chaussées (an ancient term more or less cognate with “highway”), 2 couloirs (literally “hallways”), 1 parvis (an open space in front of a church, in this case Notre-Dame), 1 chemin de ronde (a raised walkway behind the battlement of a castle), and 11 small, undefined passageways. At least those were the figures in 1957; since then quite a number of the smaller entities have been obliterated by urban renewal, while others have been confected by those or other means. A count made in 1992 gives the total number of Parisian thoroughfares as 5,414, which is 133 more than there were twenty years earlier and nearly 1,700 more than in 1865, when the city’s present limits were fixed.

Boulevard de Ménilmontant, circa 1910

Sometimes the histories of streets are inscribed in their names: Rue des Petites-Écuries because it once contained small stables, Rue des Filles-du-Calvaire (Daughters of Calvary) after a religious order that once was cloistered there, Rue du Télégraphe marking the emplacement during the revolution of a long-distance communication device that functioned through relays of poles with semaphore extensions. Sometimes streets named by long-ago committees take on a certain swagger from their imposed labels: the once-lively, nowadays flavorless Rue de Pâli-Kao given a touch of the exotic (the name is that of a battle in the Second Opium War, in 1860), the stark and drab (and once extraordinarily bleak, owing to the presence of enormous gas tanks) Rue de l’Évangile endowed with the gravity of the Gospels, the already ancient Rue Maître-Albert made to seem even more archaic in the nineteenth century by being renamed after the medieval alchemist Albertus Magnus, who once lived nearby.

Rue Cloche-Perce. Photograph by Suzanne Beaumé, circa 1900

Among the oldest thoroughfares in Paris are the streets of the Grande and Petite Truanderie, which is to say the Big and Little Vagrancy Streets. There is the Street of Those Who Are Fasting (Rue des Jeûneurs), the Street of the Two Balls, the Street of the Three Crowns, the Street of the Four Winds, the Street of the Five Diamonds, the Street of the White Coats, the Street of the Pewter Dish, the Street of the Broken Loaf—one of a whole complex of streets around Saint-Merri church (near the Beaubourg center nowadays) that are named after various aspects of the distribution of bread to the poor. Many street names were cleaned up in the early nineteenth century: Rue Tire-Boudin (literally “pull sausage” but really meaning “yank penis”) became Rue Marie-Stuart; Rue Trace-Putain (the “Whore’s Track”) became Trousse-Nonnain (Truss a Nun), then Transnonain, which doesn’t really mean anything, and then became Rue Beaubourg. Many more streets disappeared altogether, then or a few decades later, during Haussmann’s mop-up: Shitty, Shitter, Shitlet, Big Ass, Small Ass, Scratch Ass, Cunt Hair. Some that were less earthy and more poetic also disappeared: Street of Bad Words, Street of Lost Time, Alley of Sighs, Impasse of the Three Faces. The Street Paved with Chitterling Sausages (Rue Pavée-d’Andouilles) became Rue Séguier; the Street of the Headless Woman became Rue le Regrattier.

Rue Taille-Pain. Photograph by Paul Vouillemont, circa 1900

Sometimes the streets come assorted in themes, such as the Quartier de l’Europe, which encircles the Saint-Lazare train station: Rues de Bucarest, Moscou, Édimbourg, Madrid, Rome, Athènes, and so on. The exterior boulevards are called les boulevards des maréchaux because they were all named after field marshals in Napoléon’s army: Brune, Masséna, Poniatowski, Sérurier, Ney, Murat, Macdonald, etc. You’ll note that the American names—Avenue du Président-Wilson, Avenue du Président-Kennedy, Avenue de New-York, Rue Washington—are clustered in the high-hat Sixteenth Arrondissement or the adjacent western edge of the Eighth. Names associated with the labor movement or left-wing motifs, on the other hand, tend to be restricted to the northeast of the city: Avenue Jean-Jaurès, for example, after the great Socialist leader assassinated in 1914 (and there is not a sizeable city or industrial suburb in France that lacks a thoroughfare named after him) or Place Léon-Blum, after the leader of the Popular Front in the 1930s, or Place de Stalingrad (officially renamed Place de la Bataille de Stalingrad in 1993, lest there be any confusion), or indeed Rue Marx-Dormoy, although it was named not for Karl but for the Socialist politician René Marx Dormoy, assassinated in 1941, who was no relation.

Porte Jean-Jaurès, leading to Pantin, probably 1914

There is seldom a correspondence between a nominal theme and one of ambiance or architecture, and the disjunction can provide a sort of cognitive dissonance, frequently disappointing. If you expect a water tower on Rue du Château-d’Eau, for example, or think you might spot a knoll, let alone quails, on Rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles, you are more than a century too late. But the streets do develop their own thematic tendencies, not all of them imposed by architects or developers. Some of them have accrued through occupational necessity (all those large courtyards along the formerly artisan-intensive Rue Saint-Antoine) or topography (such as the tiered terraces that tumble down the hill in Ménilmontant, definitively spoiled by urban-renewal demolition and construction in the 1960s, but shown to advantage in Albert Lamorisse’s lovely short film The Red Balloon, 1956), or sometimes they were founded in the mists and are perpetuated by custom, such as the eternally carnivalesque Rue de la Gaîté. You see the way a theme will establish itself along a given street—for example, the Egyptian motif on Rue du Caire (the exception that proves the rule) or the country village ambiance of Rue de Mouzaïa or the august academic procession of Rue d’Ulm—and then be contradicted, sometimes radically, with the simple turn of a corner. The city is not just a palimpsest—it is a mass of intersecting and overlapping palimpsests. Even as it becomes socially more homogeneous, many of its streets and houses continue to bear witness to former circumstances. The tone of the Marais is still determined by medieval walls and Renaissance hôtels particuliers, and while today these are employed and intermittently decorated by the fashion industry and its ancillary commerce, if you look above the storefront level you can here and there make out traces of the centuries of misery that prevailed between the era of their construction and ours. You can admire the tenacious way the Canal Saint-Martin still assumes the existence of barge traffic, Rue de la Lune seems to have been designed for prostitution, or Rue Volta folds together about seven centuries, not necessarily including the present one.

Rue des Immeubles-Industriels, Walter Benjamin’s favorite street, circa 1910

Walter Benjamin wrote, “Couldn’t an exciting film be made from the map of Paris? From the compression of a centuries-long movement of streets, boulevards, arcades, and squares into the space of half an hour? And does the flâneur do anything different?” Paris invented the flâneur and continues to press all leisurely and attentive walkers into exercising that pursuit, which is an active and engaged form of interaction with the city, one that sharpens concentration and enlarges imaginative empathy and overrides mere tourism. The true flâneur takes in construction sites and dumps, exchanges greetings with bums and truck drivers and the women washing their sidewalks in the morning, consumes coffees and gros rouge at as many bus stop cafés as terrace-bedecked boulevard establishments, studies trash and graffiti and sidewalk displays and gutters and rooftops, devotes as much attention to the arcades filled with dentists’ offices or Indian restaurants as to the ones lined with antique shops, spends more time in Monoprix than at the Louvre.

An illustration by José Belon for Paris anecdote, by Privat d’Anglemont, 1885 edition

The history of Paris, the active and engaged history of the streets, was written by flâneurs, and each conscious step you take follows their traces and continues their walk into a continuous walk across the centuries. The great text of the streets...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.11.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseberichte |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | bohemian • French history • french photography • low life • Paris • Parisian Life • Poverty |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-32587-4 / 0571325874 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-32587-0 / 9780571325870 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 39,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich