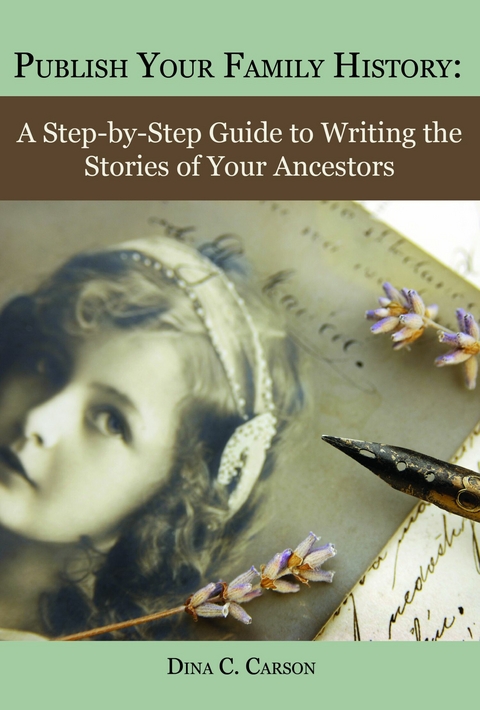

Publish Your Family History (eBook)

100 Seiten

First Edition Design Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-62287-825-3 (ISBN)

to prepare your manuscript to look like it was professionally published and * help you spread the word that you have a book available Everything you need to write and publish your family history.

If you have stories to share with your family, whether you have been researching a short time or a long time, this book will: * take you through the four stages of publishing projects * show you how publishing works * help you pick a project to publish * lead you through a research review to see what you have and what you still need to tell the stories in a compelling way * give you the skills to become a good storyteller * lead you through the process of editing * instruct you howto prepare your manuscript to look like it was professionally published and * help you spread the word that you have a book available Everything you need to write and publish your family history.

Chapter 3: Pick a Project to Publish

The most important consideration for your publishing project is that you can complete it. Part of the fun of family history is that it is never done. There will always be a new discovery or another baby born. The challenge for you, right now, is to pick a part of your research that you are willing to focus on—to the exclusion of other interesting finds—and narrow the scope enough so that the project does not become overwhelming.

In Chapter 7: Conducting a Research Review, you are going to take a critical look at the research you have already done, and decide whether what you have fits the project you have in mind, whether it will with a little more research, or whether an entirely different project may be best. In the meantime, let us explore a few ideas in more detail.

Each of the books in this series was written with the genealogist or family historian in mind. You, however, may have a project idea is unrelated to any type of genealogical research. That is fine. Each of the book projects below has a corresponding guide book with information specific to each book type.

A Family History

What is the difference between a genealogy and a family history?

In technical terms, a genealogy begins with an ancestor and moves forward in time through his or her descendants. A pedigree, on the other hand, starts with a descendant and moves backward in time through the ancestors.

For our purposes, consider a genealogy a way to pass on your well-documented research (with or without a lot of narrative). A family history, on the other hand, is less a numbered lineage, rather the stories of your family.

The challenge with any family history project is limiting the scope enough that you can tell the stories well. One consideration is the time period in which the chosen family lived. For your generation, you have personal knowledge of the people and can tell their stories from your experience. And, most probably, there are hundreds if not thousands of photographs for you to choose from to help you remember events in order to write about them and help illustrate the stories once they are written.

To write about the generation before you, you may know each family member, or you may need to consult other family members for their stories. For your grandparents’ generation (and further back), you may not have as many people to consult or as many photographs to view. Once you get back beyond the Civil War era, you may not have any photographs at all. At some point in the past, you will be relying entirely upon research.

The following are ideas for planning a family history:

Start to Finish. Pick the ancestor you wish to use as the first generation. Describe the circumstances of that ancestor’s entry into the family—not necessarily his or her birth, rather setting the scene for his or her early years. Follow the family through the number of generations you have chosen to include describing the events that affect most families—the births, schooling, marriages, professions, and deaths. Add the migrations, moves or turns of events that involved your family. Enrich the stories with enough social history so that the reader understands what it was like to live in the time and place your ancestors lived.

Photographs or Memorabilia. If you have inherited a box of photographs or memorabilia, plan your project around the people and events you find in that collection.

Letters or a Diary. Write about the people or person who wrote the letters or diary, weaving the actual text into the stories, or using the events described as the timeline for the book.

A Tragedy. Write about a defining event that affected the family, such as a natural disaster, becoming a prisoner of war, losing a fortune, or surviving the Great Depression or the Holocaust.

A Triumph. Triumphs are also defining events, such as suddenly becoming wealthy or famous, being elected to an important public office, and so on.

An Ancestor and the People Known to Him or Her. A book of this type could include parents, siblings, grandparents, children and grandchildren, cousins, aunts and uncles—essentially five generations—the two before and the two following your main character.

A Single Generation. If you would rather focus on an individual or a couple (e.g. your parents or grandparents) than a multi-generational family line, consult, Publish a Biography: A Step-by-Step Guide to Capturing the Life and Times of an Ancestor or a Generation. The difference is mostly in the level of detail required.

A Genealogy

By my definition (above), a genealogy is a little less about writing and a little more about passing along your research to other researchers. Publishing your research is a valuable effort, in an of itself. If you have plenty of research to choose from, but are not quite ready to write the stories, publishing a genealogy will give you experience with the publishing process.

The following are ideas for planning a genealogy:

Every Descendant of a Single Ancestor. That may be your grandparents or the first immigrant. The more generations you go back, the more challenging it will be to ensure that the lines are complete.

Direct Descendants of a Single Ancestor. Include the siblings in each generation, but the detailed information only for your direct line.

Female Lines. Your mother and her mother, and her mother, and so on, as far back as you have researched.

A Surname Line. Beginning with the first ancestor of a given surname (a female), following her surname (male) line backward. Another section could include the wives of the male ancestors as collateral lines.

A Direct Line to a Specific Ancestor. Beginning with yourself, you could trace back across different surnames to a specific ancestor, such as an American President or a Salem witch (the kind of research to join a lineage society).

A Surname Study. Focus on a surname in a particular region (e.g. The Bakers of Campbell County, KY), within a national database (e.g. Revolutionary War soldiers or patriots), or across a complete record set (e.g. federal census records).

If you have done the research, but are not quite ready to write the narrative, you will find additional details about numbering systems and formal genealogical writing in Publish Your Genealogy: A Step-by-Step Guide for Preserving Your Research for the Next Generation.

A Local History

There are endless possibilities for writing local histories. All families have elements of local history in their stories, right? They attended local schools, worked in local businesses, joined community organizations, participated in local government, and lived in neighborhoods or rural communities.

The following are ideas for elements of local history to enhance your family history. Any of these ideas could become a local history unto itself:

Professions. Farming, mining, ranching, medicine, crafts, craftsmanship, banking, manufacturing, logging, science, technology, information, inventions, merchants, wholesalers, working conditions, etc.

Institutions. Schools, courts, military units, libraries, government agencies, fire departments, law and order, etc.

Associations. Sports teams, Masons, Odd Fellows, Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, 4H, philanthropic, social, fraternal, activist, etc.

Religious Groups. Churches, synagogues, mosques, religious movements, religious colonies, etc.

Transportation. Freighters, wagon roads, railroads, stage companies, stations or airports, riverboats, barges, trails or roads, aerospace, aeronautics, etc.

People. Famous or notorious, leaders, office holders, women, children, what became of (e.g. a school class), the poor, ethnic groups, religious groups, etc.

Events. Natural disasters, on this day, during this year, anniversaries, economic depression, loss or gain of a major employer, politics, etc.

Architecture. Neighborhoods, downtown, building styles, building techniques, public buildings, historic homes, etc.

Transitions. Town into city, fort into town, farm into metropolis, etc.

Customs. Marriages, burials, holidays, celebrations, 4th of July, parades, rallies, expectations, manners, roles for men and women, expectations of children, economic class, etc.

Entertainment. Music, art, dance, theater, movies, plays, books, museums,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.3.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Familie / Erziehung |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Hilfswissenschaften | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-62287-825-6 / 1622878256 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-62287-825-3 / 9781622878253 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich