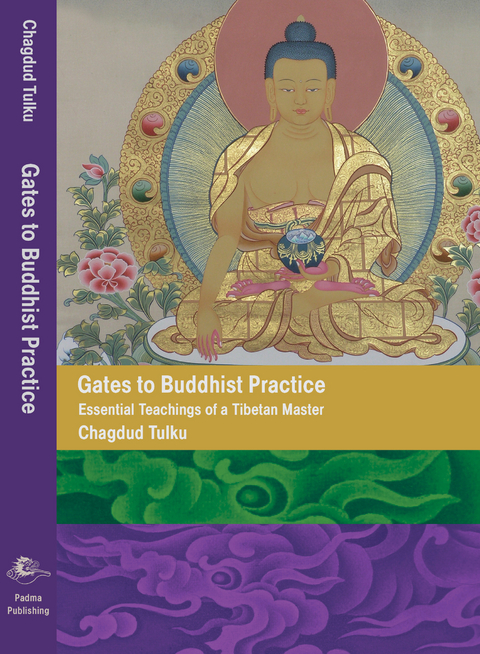

Gates to Buddhist Practice (eBook)

304 Seiten

Padma Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-881847-40-3 (ISBN)

This is a rare book: a brilliant guide to the spiritual path by a master of outstanding qualities who has taught in the West now for many years. Simple yet profound, intimate and immediate, Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche's words speak to us all. They show how, by bringing the light of wisdom and compassion into every corner of our lives, we can come to understand the mind and transform its emotions, and so discover the boundless freedom of our true nature."e; ~Sogyal RinpocheIn Gates to Buddhist Practice, His Eminence Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche presents the traditional wisdom of the Vajrayana path. Since its original publication, Rinpoche continued to teach widely and address the questions of sincere students grappling with the many challenges, concerns, and even skepticism encountered in genuine spiritual practice. These questions, as well as Rinpoche's incisive responses, form the basis of the material added to this revised edition. Rinpoche provides insight into formal meditation practice and demonstrates how spiritual truths can be of immediate help in our daily lives. Thus new readers will benefit from other students' efforts to clarify their understanding with an authentic spiritual teacher. H.E. Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche (1930-2002) was a highly revered Tibetan meditation master, artist, and healer who taught extensively in the East and West. His other books are Life in Relation to Death and Lord of the Dance, his autobiography. His Bodhisattva Peace Training teachings can be found in Change of Heart, compiled and edited by Lama Shenpen Drolma.

2

Working with Attachment and Desire

To understand how suffering arises, practice watching your mind. Begin by simply letting it relax. Without thinking of the past or the future, without feeling hope or fear about this or that, let it rest comfortably, open and natural. In this space of the mind, there is no problem, no suffering. Then something catches your attention—an image, a sound, a smell. Your mind splits into inner and outer, self and other, subject and object. In simply perceiving the object, there is still no problem. But when you zero in on it, you notice that it’s large or small, white or black, square or circular. Then you make a judgment—deciding for example, that it’s pretty or ugly—and you react: you like it or you don’t.

The problem starts here, because “I like it” leads to “I want it.” Similarly, “I don’t like it” leads to “I don’t want it.” If we like something, want it, and can’t have it, we suffer. If we want something, get it, and then lose it, we suffer. If we don’t want it but can’t keep it away, again we suffer. Our suffering seems to stem from the object of our desire or aversion, but that’s not so. We suffer because the mind splits into object and subject and becomes involved in wanting or not wanting something.

We often think the only way to create happiness is to try to control the outer circumstances of our lives, to try to fix what seems wrong or to get rid of everything that bothers us. But the real problem lies in our reaction to those circumstances.

There was once a family of shepherds living in Tibet. On a bitterly cold winter day, it was the son’s turn to look after the sheep, so his family saved him the largest and best piece of meat for dinner. Upon his return, he looked at the food and burst into tears. When asked what was wrong, he cried, “Why am I always given the worst and smallest portion?”

We have to change the mind and the way we experience reality. Our emotions propel us through extremes, from elation to depression, from good experiences to bad, from happiness to sadness—a constant swinging back and forth. All of this is the by-product of hope and fear, attachment and aversion. We have hope because we are attached to something we want. We have fear because we are averse to something we don’t want. As we follow our emotions, reacting to our experiences, we create karma—a perpetual motion that inevitably determines our future. We need to stop the extreme swings of the emotional pendulum so that we can find a place of equilibrium.

When we begin to work with the emotions, we apply the principle of iron cutting iron or diamond cutting diamond. We use thought to change thought. A loving thought can antidote an angry one; contemplation of impermanence can antidote desire.

In the case of attachment, begin by examining what you are attached to. You might think that becoming famous will make you happy. But your fame could trigger jealousy in someone, who might try to kill you. What you worked so hard to create could become the cause of greater suffering. Or you might work diligently to become wealthy, thinking this will bring happiness, only to lose all your money. The source of our suffering is not the loss of wealth in itself, but rather our attachment to having it.

We can lessen attachment by contemplating impermanence. It is certain that whatever we’re attached to will either change or be lost. A family member may die or go away, a friend may become an enemy, a thief may steal our money. Even our body, to which we’re most attached, will be gone one day. Knowing this not only helps to reduce our attachment, but gives us a greater appreciation of what we have while we have it. There is nothing wrong with money in itself, but if we’re attached to it, we’ll suffer when we lose it. Instead, we can appreciate it while it lasts, enjoy it, and share it with others without forgetting that it is impermanent. Then if we lose it, the emotional pendulum won’t swing as far toward sadness.

Imagine two people who buy the same kind of watch on the same day at the same shop. The first person thinks, “This is a very nice watch. It will be helpful to me, but it may not last long.” The second person thinks, “This is the best watch I’ve ever had. No matter what happens, I can’t lose it or let it break.” If both people lose their watches, the one who is more attached will be more upset than the other.

If we are fooled by our experience and invest great value in one thing or another, we may find ourselves fighting for what we want and against any opposition. We may think that what we’re fighting for is lasting, true, and real, but it’s not. It is impermanent, it’s neither true nor lasting, and ultimately it’s not even real.

We can compare our life to an afternoon at a shopping center. We walk through the shops, led by our desires, taking things off the shelves and tossing them in our baskets. We wander around looking at everything, wanting and longing. We smile at a person or two and continue on, never to see them again.

Driven by desire, we fail to appreciate the preciousness of what we already have. We need to realize that this time with our loved ones, our family, our friends, and our co-workers is very brief. Even if we lived to be a hundred and fifty, we would have very little time to enjoy and make the most of our human opportunity.

Young people think their lives will be long; old people think theirs will end soon. But we can’t assume these things. Life comes with a built-in expiration date. There are many strong and healthy people who die young, while many of the old, sick, and feeble live on and on. Not knowing when we’ll die, we need to develop an appreciation for and acceptance of what we have rather than continuing to find fault with our experience and incessantly seeking to fulfill our desires.

If we start to worry whether our nose is too big or too small, we should think, “What if I had no head? Now that would be a problem!” As long as we have life, we should rejoice. Although everything may not go exactly as we’d like, we can accept this. If we contemplate impermanence deeply, patience and compassion will arise. We will hold less to the apparent truth of our experience, and the mind will become more flexible. Realizing that one day this body will be buried or cremated, we will rejoice in every moment we have rather than make ourselves or others unhappy.

Now we are afflicted with “me-my-mine-itis,” a condition caused by ignorance. Our self-centeredness and self-interest have become very strong habits. In order to change them, we need to refocus. Instead of always concerning ourselves with “I,” we must direct our attention to “you,” “them,” or “others.” Reducing self-importance lessens the attachment that stems from it. When we focus beyond ourselves, ultimately we realize the equality of ourselves and all other beings. Everybody wants happiness; nobody wants to suffer. Our attachment to our own happiness expands to encompass attachment to the happiness of all.

Until now, our desires have tended to be transient, superficial, and selfish. If we are going to wish for something, let it be nothing less than complete enlightenment for all beings. That is something worthy of desire. Continually reminding ourselves of what has true worth is an important element of spiritual practice.

Desire and attachment won’t disappear overnight. But desire becomes less ordinary when we replace our worldly yearning with the aspiration to do everything we can to help all beings find unchanging happiness. We don’t have to abandon the ordinary objects of our desire—relationships, wealth, success—but as we contemplate their impermanence, we become less attached to them. We begin to develop spiritual qualities by rejoicing in our good fortune while recognizing that it won’t last.

As attachment arises and disturbs the mind, we can ask, “Why do I feel attachment? Is it of any benefit to myself or others? Is this object of my attachment permanent or lasting?” Through this process, our desires begin to diminish. We commit fewer of the harmful actions that result from attachment, and so create less negative karma. We generate more fortunate karma, and mind’s positive qualities gradually increase.

Eventually, as our meditation practice matures, we can try something different from contemplation, from using thought to change thought. We can use an approach that reveals the deeper nature of the emotions as they arise. If you are in the midst of a desire attack—something has captured your mind and you must have it—you won’t get rid of the desire by trying to repress it. Instead, you can begin to see through desire by examining it. When it arises, ask yourself, “Where does it come from? Where does it dwell? Can it be described? Does it have any color, shape, or form? When it disappears, where does it go?”

You can say that desire exists, but if you search for the experience, you can’t quite grasp it. On the other hand, if you say that it doesn’t exist, you’re denying the obvious fact that you feel desire. You can’t say that it exists, nor can you say that it does not exist. You can’t say that it both does and does not exist, or that it neither exists nor does not not exist. This is the meaning of the true nature of desire beyond the extremes of conceptual mind.

Our failure to understand the essential nature of an...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.12.1993 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Buddhismus |

| ISBN-10 | 1-881847-40-3 / 1881847403 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-881847-40-3 / 9781881847403 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 700 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich