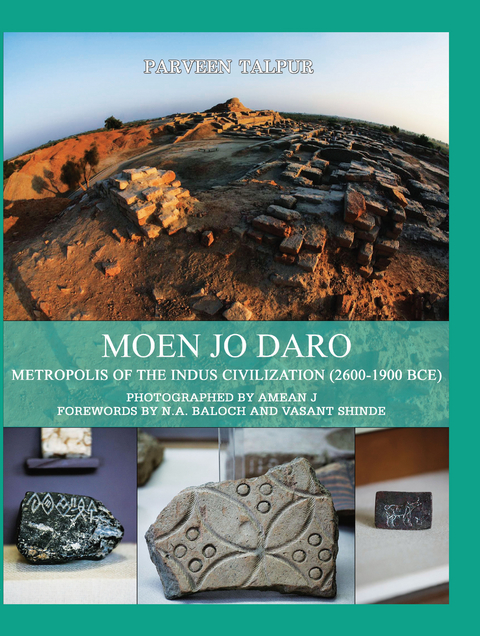

Moen jo Daro (eBook)

178 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-63192-223-7 (ISBN)

Moen jo Daro: Metropolis of the Indus Civilization (2600-1900) BCE) is a personal view book on the largest and the most elaborate city of the Indus Civilization, located in present day Pakistan. Beginning with the myths and legends surrounding the civilization, Moen jo Daro ends with an appeal for its 3-dimensional digital preservation in the modern age. In between it covers the accidental discovery of the city under the foundations of a Buddhist stupa, the life of its mysterious inhabitants, and the unknown ideology they followed as well the strange, undeciphered writing they left behind. The book is not a mere description of the architectural remains and the artifacts discovered in their ruins. It examines the theories of its rise and fall in the larger context of the Indus civilization. In the absence of any direct source the author has attempted to reconstruct its picture by presenting original photographs captured exclusively for this book, incorporating legends, folklore, and languages of the region, and her own understanding of the ancient signs and symbols which she researched on during her seven years of research at the Cornell University, New York. The book is meant for general readers and the scholars and students, and is a must read for an international audience as well. Pakistan is on the center stage of global politics and the world is keen to know it beyond its typical day-to-day reporting.

1

SEEKING LIFE IN THE MOUND OF DEAD

Mother Goddess by Laila Shahzada: Courtesy of Shahien Shahzada

“Alas, when Sikander sought he did not find what Khizr found unsought.”

- Nizami in Sikandernama

One afternoon, while walking in the fields around my village in lower Sindh, we kids stumbled upon a dollhouse camouflaged between the cotton crops. Under its thatched roof and a floor strewn with pebbles, stood two clay dolls; one of the girls reached out for a doll, another warned her “do not touch. It’s a devi.”

Years later I realized the dollhouse was a crudely built diorama and the dolls were actually the existing specimens of mother goddesses that Marija Gimbutas had discovered in the Neolithic ruins of ‘Old Europe.’ South Asian Neolithic era was no different; Jean-Francois Jarrige had discovered thousands of them in Mehrgarh (Balochistan) where he also traced the roots of Indus Civilization. Mother goddess cult was to ripen and loom large in that Civilization and if Goddesses in ancient world played dual roles of healers and killers, givers of life and angels of death, they might have possessed the power of granting immortality too, or at least, such must have been the ancient belief. Legend has it that out of all the places in the entire world, Alexander the Great searched for an immortal life in the Indus region. History, on the other hand, records that he came across Jain saints to whom the purpose of life was to end the cycle of life. According to Greek chronicles; one of them became Alexander’s mentor another accompanied him on his return journey. On the way he predicted Alexander’s death and burnt himself to ashes!

In this day and age the quest is not to seek immortality but merely the truth (if any) behind the stories of this undying human quest. In the 1950s, Professor Samuel Noah Kramer, one of the foremost authorities on Sumerian literary works of Assyriology, at the University of Pennsylvania, had drawn the attention of Indus archaeologists towards a distant source that would help in the reconstruction of Indus’ story. “There is, however, one possible source of significant information about the Indus Valley Civilization which is still untapped: the inscriptions of Sumer.” He wrote while translating a Sumerian text that spoke of a ‘flood story’ and a Sumerian ‘Noah,’ who after the ‘Deluge’ was transported to a land called Dilmun where he lived as an immortal among the Gods. Dilmun, according to the text, was located somewhere in the East of Sumer and was described as a ‘blessed, prosperous land dotted with great dwellings.’ Kramer speculated that Dilmun, the paradise on earth, was a reference to ancient Indus cities. He even visited Pakistan to test his hypothesis but eventually it was his student, George F. Dales, who undertook a hectic search of the lost paradise on the Makran coast, the dreaded Gedrosia of the Persians and the Greeks. Cyrus, the Achaemenid emperor, had crossed its desert with seven survivors whereas Alexander had lost half of his army in its burning sands. Dales’ journey, however, was not in vain it took him to Sutkagen-dor1 the westernmost port of Indus Civilization on the Pakistan-Iran borders. On his way he re-examined Sokta Koh and later excavated Balakot. However, there is nothing in his account comparable to the paradise on Earth. Dilmun eventually came to be identified with Bahrain whereas Makran is supposedly Meluhha of the Sumerian texts.

“History is a set of lies that people have agreed upon,” Napoleon Bonaparte, another great conqueror stated. To put it mildly, history is nothing but legends agreed upon. It is true that history is a subject with enough room for distortions, and a profound work of history will be the one based on hard facts. However, as we dive deeper in the past, where written sources are not available, the line between legend and history becomes thinner; this is where we must attempt to sift history from legends before rejecting them.

Legends, religious traditions, rituals and even ancient words, are capable of enhancing the picture of the past. But placing them in their proper historic and especially prehistoric context (where evidence is scarce) is yet another challenge as they provide only elusive links to their origins; the journey to reconstruct the ancient past, therefore, can be surreal but must continue. To begin this book with Moen jo Daro is not because it is the richest repository of material evidence waiting to be related to its legends but because a thorough knowledge of its abundant architectural remains and artifacts is a prerequisite for such an undertaking. Clues can be hidden in the folk heritage preserved and scattered in the vast Indus region, but identifying the relevant clues requires a good knowledge of the site. The following pages are therefore not all about legends but more of facts about Moen jo Daro where a stray legend or an ancient word can befit and mend the picture of the past.

Moen jo Daro: Poster of a Devastated City

From the yard of the site Museum, the ruins of Moen jo Daro appear as a perfect poster of a city devastated - roofs blown off, walls broken, bricks and potsherds scattered all around. The dome of a Buddhist stupa that once crowned the site has diminished to a mere circular wall. The reliefs and niches carved on its exterior are now scraped off, leaving the wall bare and broken. Only on cloudless mornings when the fiery glow of the rising sun lends life to the bricks, they turn bloody red just to reveal how Martian the dead city might have looked in its livelier moments.

From the Museum, it is also hard to visualize any civic pattern in the heap of smashed structures. Features begin to emerge only while walking through the dusty lanes of the site.

Path from the Museum to Moen jo Daro

On reaching the base of the Buddhist stupa, it is easy to figure out remains of walls that divide the floor plans of the surrounding structures. The rooms are without roofs, pillars that once held them aloft have crumbled, rooted firmly in the ground are only their stubs. Nearby are the verandahs surrounding a quadrangle, with the Great Bath in its midst, stairs can be seen leading to the Bath floor. These architectural remains, well-guarded by a fortified wall, were the public buildings of Moen jo Daro. Michael Jansen, who has been documenting the city’s architecture through a joint project of ISMEO and Aachen University, suggests that the area was raised by constructing a forty feet high platform tapering to twenty feet at one end. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, the British archaeologist, named this elevated area, the Citadel Mound.

Before the excavations, the only signs suggesting the existence of a long lost human settlement at Moen jo Daro were the fringes of a Buddhist stupa. Built thousands of years after the desertion of Moen jo Daro, the stupa stood on the peak of a high mound surrounded by a cluster of smaller mounds. Generations of nearby villagers had lived with the belief that the mound was a colossal grave wherein rested many a dead. They called it Moen jo Daro, this can be translated into English as Mound of the Dead. The site came to the notice of Archaeological Survey of India in the early years of twentieth century. According to Sir John Marshall who was the director general of the Survey at that time, “The site had long been known to district officers in Sindh, and had been visited more than once by local archaeological officers, but it was not until 1922, when Mr. R.D. Banerji started to dig there that the prehistoric character of its remains was revealed.”2

Those prehistoric remains turned out to be of a large city, divided in two parts, the citadel area, which had the administrative or the communal buildings, and a large low lying residential area built on a grid plan. The map of the site plan shows clear demarcation between these areas. Though these are not islands but they bear “some resemblance to the map of the British Isles3”. Observed K.N. Dikshit, who drafted the first map of Moen jo Daro.

Image by J. Mark Kenoyer

Courtesy of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan

That map can easily change shape if further excavations are allowed as still much lies beneath and beyond the exposed structures and mounds. The occasional discoveries of artifacts from the city and often from its outskirts prove that Moen jo Daro was much larger in size.

In 2009, during a salvage operation the seals displayed below were recovered from the DK Area of Moen jo Daro. The top seal is engraved with a combination of features. On the right side is the realistic depiction of a tree and a man holding a jar; on the left side is a geometric pattern. In between these are regular signs of four vertical strokes followed by a U sign and a man sign standing between two vertical lines. The second seal below is broken but it seems to be a square button seal showing parts of a geometric pattern.

Recently Discovered Seals from Moen jo Daro.

Courtesy of Qasim Ali Qasim, Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan.

Moen jo Daro was actually the metropolis of a 5000 year old civilization. Excavations, since the first quarter of the twentieth century, have exposed many structures indicating a comfortable and busy life for people who lived there. The Citadel Mound conjures up images of farming, trade and culture – bullock-carts loaded with grains outside the granary, bales of cotton and other merchandize ready for caravans leaving for distant lands, robed priests getting in and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.8.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-63192-223-8 / 1631922238 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-63192-223-7 / 9781631922237 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich