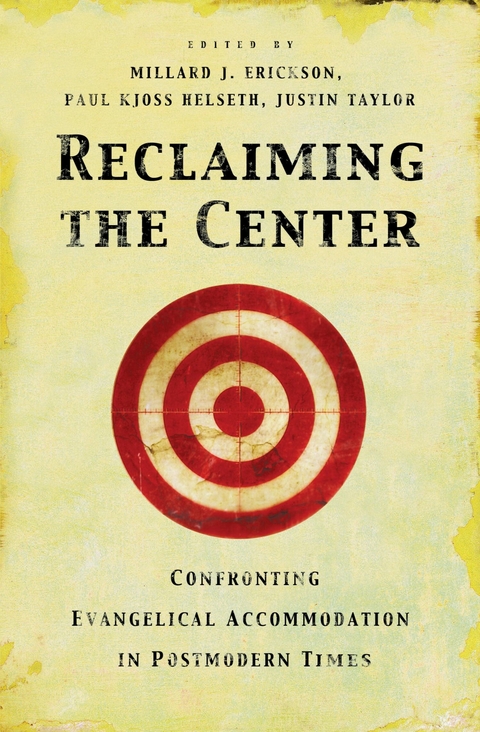

Reclaiming the Center (eBook)

368 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-1725-9 (ISBN)

Millard J. Erickson (PhD, Northwestern University) is distinguished professor of theology at Western Seminary in Portland, Oregon. He is a leading evangelical spokesman and the author of numerous volumes, including the classic text Christian Theology.

Millard J. Erickson (PhD, Northwestern University) is distinguished professor of theology at Western Seminary in Portland, Oregon. He is a leading evangelical spokesman and the author of numerous volumes, including the classic text Christian Theology.

DOMESTICATING THE GOSPEL:

A REVIEW OF GRENZ’S

RENEWING THE CENTER1

RESPONSIBLE THEOLOGICAL REFLECTION must simultaneously embrace the best of the heritage from the past, and address the present. If theologians restrict themselves to the former task, they may become mere purveyors of antiquarian artifacts, however valuable those artifacts may be; if they focus primarily on the latter task, it is not long before they squander their heritage and become, as far as the gospel is concerned, largely irrelevant to the world they seek to reform, because wittingly or unwittingly they domesticate the gospel to the contemporary worldview, thereby robbing it of its power. Stan Grenz, I fear, is drifting toward the latter error.

CONTENT

As usual in his writings, Grenz in this book is free of malice, and, provided one is familiar with the jargon of postmodern discussion, reasonably lucid. The book’s ten chapters can be divided into two parts. Grenz begins by citing a representative sample of voices that find contemporary evangelical the-ology in disarray—though admittedly these analyses do not all agree. So in the first four chapters, and part of the fifth, Grenz treats evangelicalism historically “as a theological phenomenon,” trying to “draw from the particu-larly theological character of the movement’s historical trajectory” (15).Accepting William J. Abraham’s analysis—that the term “evangelical”embraces at least three constellations of thought, viz. the magisterial Reformation, the evangelical awakenings of the eighteenth century, and modern conservative evangelicalism—Grenz devotes the first two chapters, respectively, to the material principle and the formal principle of evangelical thought. In both cases he is attempting to tease out a “trajectory” of historical development. With respect to the material principle: Luther’s commitment to justification by faith, modified by Calvin’s quest for sanctification, augmented by Puritan and Pietist concern for personal conversion, sanctified living, and assurance of one’s elect status, decline into comfortable confor-mity to outward forms, until the awakenings in Britain and the American colonies charged them with new life. The effect was a focus on “convertive piety” (passim) and concern for transformed living, rather than adherence to creeds. Evangelical theology focused on personal salvation.

As for the formal principle (chapter 2), contemporary conservative views of the Bible have not been shaped exclusively by Luther or Calvin, but also by Protestant scholastics who “transformed the doctrine of Scripture from an article of faith into the foundation for systematic theology” (17). At the end of the nineteenth century the Princeton theologians turned the doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture into “the primary fundamental” (17). This was passed on to neo-evangelical theologians, the thinkers who from the middle of the twentieth century tried to lead evangelicalism out of its introspection and exclusion, and into engagement with the broader culture.

Chapters 3, 4, and 5 carry on Grenz’s analysis of contemporary evangelicalism by studying three pairs of men. The first generation of neo-evangelical theologians can be represented by Carl F. H. Henry and Bernard Ramm, the former setting a rationalistic and culturally critical cast to neo-evangelical theology, and the latter trying to lead evangelical theology out of “the self-assured rationalism he found in fundamentalism. Consequently, he became the standard-bearer for a more irenic and culturally engaging evangelicalism” (18). In the next generation, the polarity is Millard Erickson and Clark Pinnock, the former an establishment theologian who systematized neo-evangelical theology, the latter reflecting a theological odyssey that wanted to fulfill the evangelical apologetic ideal by engaging in dialogues with alternative views. He thereby carries on the irenic tradition of Ramm. The fifth chapter proposes that the polarities in the third generation can be aligned with Wayne Grudem and John Sanders.

Is this polarity so great that David Wells is correct in thinking that we are on the verge of evangelicalism’s demise? Or does Dave Tomlinson’s announcement of a post-evangelical era point the way ahead? In the second half of chap-ter 5, Grenz opts for neither stance, but suggests that the emerging task of evangelical theology is coming to grips with postmodernity. Recognizing the ambiguities in this term, Grenz identifies the heart of postmodernism in the epistemological arena. It adopts a chastened rationality (his expression), and marks a move from realism to the social construction of reality, from meta-narrative to local stories. The rest of the book teases out Grenz’s proposal.

The next three chapters constitute the heart of the book. Chapter 6, “Evangelical Theological Method After the Demise of Foundationalism,” is a summary of the book Grenz jointly wrote with John R. Franke entitled Beyond Foundationalism.2 Grenz provides his take on “the rise and demise of foundationalism in philosophy” (185) before offering his own alternative. Here, he says, he has been influenced especially by Wolfhart Pannenberg and George Lindbeck. The former’s appeal to the eschatological nature of truth, i.e., to the eschaton as the “time” when truth is established, responds to the reality that “God remains an open question in the contemporary world, and human knowledge is never complete or absolutely certain” (197). Lindbeck’s rejection of the “cognitive-propositionalist” and the “experiential-expressive” approaches in favor of a “cultural-linguistic” approach supports Pannenberg’s emphasis on coherence (the view that affirms that a structure of thought is believable because its components cohere—they hang together). In the shadow of Wittgenstein, Lindbeck in effect insists that doctrines are “the rules of dis-course of the believing community. Doctrines act as norms that instruct adherents how to think about and live in the world” (198). Like rules of grammar, they exercise a certain regulative function in the believing community, but they “are not intended to say anything true about a reality external to the language they regulate. Hence, each rule [doctrine] is only ‘true’ in the context of the body of rules that govern the language to which the rules belong” (198). Lindbeck calls for an “intratextual theology” that aims at “imaginatively incorporating all being into a Christ-centered world” (199).3 Within evangelicalism, Grenz finds most hope in the work of Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff, especially in their claim that Christian theology “is an activity of the community that gathers around Jesus the Christ” (201). This constitutes a “communitarian turn” in evangelical theology: “we have come to see the story of God’s action in Christ as the paradigm for our stories. We share an identity-constituting narrative” (202). This is not the same as old-fashioned liberalism, Grenz asserts, because (1) liberalism was itself dependent on foundationalism, which Grenz rejects; and (2) older liberalism tended to give primacy to experience such that theological statements were mere expressions of religious experience, while in the model that Lindbeck and Grenz are propounding “experiences are always filtered by an interpretive framework that facilitates their occurrence. . . .[R]eligions produce religious experience rather than merely being the expressions of it” (202-203). Grenz wants to go a step farther, a step beyond Lindbeck:the task of theology, he argues, “is not purely descriptive . . . but prescriptive” (203, emphasis his), i.e., it “ought to be the interpretive framework of the Christian community” (203). Taking a leaf out of Plantinga’s insistence that belief in God may be properly “basic,” Grenz writes, “In this sense, the specifically Christian experience-facilitating interpretative framework, arising as it does out of the biblical gospel narrative, is ‘basic’ for Christian theology” (203).This is not a return to foundationalism by another name, Grenz insists, because the “cognitive framework” that is “basic” for theology does not precede theology; it is “inseparably intertwined” with it (203-204). The appropriate test becomes coherence, not the disparate and often integrated data of foundationalism (exemplified, Grenz asserts, in a Grudem).

In all this, Grenz does not want to lose sight of the Bible, which must be the “primary voice in theological conversation” (206). But he wants to distance himself from the modern era’s misunderstanding of Luther’s sola Scriptura. The theologians of the modern era, Grenz says, traded the “ongo-ing reading of the text” for their own grasp of the doctrinal deposit that they found in its pages and which was “supposedly encoded in its pages centuries ago” (206). It is far wiser to incorporate speech-act theory, and be sensitive to what the text does, how it functions, what it performs. “The Bible is the instrumentality of the Spirit in that the Spirit appropriates the biblical text so as to speak to us today” (207). The reading of text, in this light, is “a community event.” Grenz...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.11.2004 |

|---|---|

| Co-Autor | D. A. Carson, Douglas Groothuis, J. P. Moreland, Garrett Deweese, R. Scott Smith, Ardel Caneday, Stephen J. Wellum, Kwabena Donkor, William G. Travis, Chad Owen Brand, James Parker III |

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Religionspädagogik / Katechetik | |

| Schlagworte | Arminian • Bible study • Biblical • Calvinist • Christ • Christian Books • Church Fathers • Doctrine • Faith • God • Gospel • hermeneutics • Prayer • Reformed • Systematic Theology • Theologian |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-1725-6 / 1433517256 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-1725-9 / 9781433517259 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich