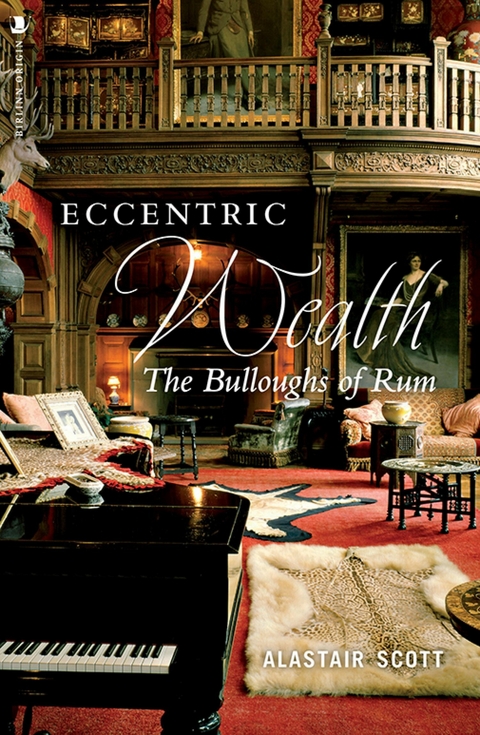

Eccentric Wealth (eBook)

272 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-0-85790-052-4 (ISBN)

Alastair Scott was born in Edinburgh in 1954. He now lives with his wife, Sheena, on Skye (with occasional bouts of vagrancy), working as a photographer, writer and broadcaster.

In Eccentric Wealth, Alastair Scott traces the life of Lancashire industrialist Sir George Bullough in this absorbing biography which explores his family's connection with the Hebridean island of Rum, particularly the building of Kinloch Castle, the most intact preserve of Edwardian highliving to be found in Britain. Based on new information, the book offers a fascinating insight into the life and times of one of the great eccentrics of his age, including the Bullough myths and scandals which continue to make extraordinary reading more than a hundred years later.

Alastair Scott was born in Edinburgh in 1954. He now lives with his wife, Sheena, on Skye (with occasional bouts of vagrancy), working as a photographer, writer and broadcaster.

2

Weft Fork and Slasher – James Bullough

Accrington (a ‘town surrounded by oaks’ in Saxon times) all but fills a long, abrupt valley high in the Lancashire dales. The oaks have long gone, but the odd copse of trees breaks the horizon where a fringe of farms and fields make a last stand against the upthrust of houses. These form an impressive symmetry of parallel terraces running steeply down to the town centre. Once a dense amphitheatre of smokestacks, the town’s notable landmarks now are an abundance of churches, the finest market hall in the county and the railway line which straddles the centre on a viaduct. The air of decline is heavy. The heart is a shopping centre, the pulse weak. Lancashire wit and friendliness remain irrepressible, but the sense of abandonment is unmistakable, as if all the locals have really got left is their football club. Accrington Stanley’s fame rests on being very old, unwilling to succumb to destitution and failing to recognise when it should be defeated by superior teams. ‘Th’ Owd Reds’ seem to bear a double burden of the community’s pride and hopes.

For its survival in the age of emerging industrialization, Accrington was fortunate in its geology and geography. The Burnley coalfield extended to the town’s limits and provided both fuel and mining employment. The surrounding hills were a source of gritstone for building and mudstone for the ‘Accrington brick’ that brought initial and enduring commercial fame. A reliably wet climate ensured the river Hyndburn flowed strongly through the town’s centre, and this was harnessed for both power and washing in the new processes of cotton manufacture. The Leeds-Liverpool canal looped the outskirts of the town and railways brought connections east, west and, crucially, south to Manchester. When technology led to the building of factories, then inevitably Accrington was poised to take full advantage of its commanding position. There was abundant labour to move into town from the rural cottage industry of handloom weavers, now becoming redundant, and enough creative vigour in the community for Accrington to spawn its own inventors and radically alter the wider world. What was to distinguish this town from a plethora of others which enjoyed similar advantages and growth was the breadth and diversity of its industrial base. The cotton industry dominated, but around it was formed a solid bastion of related and unrelated manufacturers.

At school certain names and dates were drilled into the minds of pupils in connection with the development of the weaving industry. In my case, little of what we learned remains except a vague recollection of Hargreaves and something wonderful called a spinning-jenny. In researching this book I have had to address that deficit.

In fact it was an earlier inventor, a clockmaker called John Kay, who is credited with the first revolutionary idea. In 1733 Kay dreamed up the flying shuttle, which exponentially increased weaving speed and enabled wider bolts of cloth to be woven. In 1764 came the spinning-jenny, supposedly invented by Lancastrian James Hargreaves. The tale persists that when his daughter, Jenny (coincidentally also an old name for an engine), accidentally knocked over his spinning wheel it gave him the idea for a way of activating eight, later eighty, spindles from one turning wheel.

The reality is somewhat different; Hargreaves was given, and later claimed as his own, the preliminary plan for the spinning-jenny by a man called Thomas Highs, a brilliant inventor who never had the funds or acumen to protect his ideas. The spinning-jenny’s flaw was that the threads it produced were coarse and weak and could only be used for the weft (the threads woven at right angles to the length of the warp). This problem was also solved by the unfortunate Highs. He discovered that sets of paired rollers turning at different speeds would produce the much-desired, fine, strong thread. The problem was how to power the machine. The ‘Frame’, as it was called, was too heavy to be turned by hand. Highs adapted it to the principles of the millwheel and harnessed the power of water. His Water Frame was adopted by wigmaker Richard Arkwright, who joined forces with John Kay. Kay had been all but bankrupted by litigation fees when trying to enforce his patents for the flying shuttle. Together they turned the Water Frame into a commercial success and are credited with inventing it.

So, two inventions revolutionised spinning and one weaving. The other famous figure in cotton manufacture is Edmund Cartwright, a clergyman, who is recognised as the progenitor of the first power loom, despite never having made a viable model. His best effort of 1786 provided the breakthrough and others redesigned it into a successful machine.

Nowhere in the history of weaving during the industrial revolution do James or John Bullough feature prominently. Yet it is arguable that their inventions and enterprise over the years contributed as much to the advances in output and efficiency in the cotton industry as any of their celebrated predecessors. What has been recognised is that its local sources of both genius and prototype machinery allowed Accrington to lead the world for decades, and without them, the Lancashire cotton industry would have died in its infancy. What differentiates the Bulloughs’ inventions from those of Kay, Hargreaves, Arkwright and Cartwright is that theirs were not revolutionary changes but incremental improvements of existing processes. Radical they certainly were, and they numbered many dozens, and they carried technology to new heights over a long period.

In a thoroughly unreliable family tree the earliest mention of the Bullough origins in Lancashire dates back to c.1200, with a ‘Stephen Bulhalgh’ resident in Kirkdale. The family surname metamorphosed through various forms, some Norman – de Bulhalgh, Bulhaigh, Bulhaighe and Bulowghe – to the first recorded ‘Bullough’, born around 1580 at Little Hulton in the Parish of Deane. This was close to Bolton, some fifteen miles south of Accrington. Over the next seven generations the family migrated no further than five miles away and, in 1799, the future co-founder of the world-dominating Globe Works was born in the hamlet of Deane. He was named after his father.

His parents, James and Anne Bullough, were a typical working-class couple of impecunious means. Life for the masses was still a crude struggle for existence. Candles and oil lamps provided light. The penny post had yet to appear, universal education did not exist and the rush to steam power was decades away. James senior was a handloom worker in what was still predominantly a cottage industry. Powerlooms had been invented, but their use was not widespread, although several small spinning factories using water power had started up in nearby cities.

The young James was seven when he was apprenticed to a handloom weaver in nearby Westhoughton. Despite his lack of schooling he possessed the natural gifts of an inventor’s eye and an engineer’s mind. While progressing from hand-weaving through a series of mill jobs he noticed how much time and material was lost whenever the weft broke. Using some of his sister’s plaited hair and linking it to a bell, he adapted his loom so it sounded a warning each time the weft tension slackened. The Self-Acting Temple, as it became known, was his first major success. Although the financial rewards were small, his ability was recognised and he soon became an ‘overlooker’ (foreman) at mills in Bolton and Bury. In 1824 he married Martha Smith.1 The following year he became manager of a small factory, where he introduced his latest improved hand-loom, the Dandy Loom.

James Bullough’s innovations did not meet with universal approval. This was an era of inflammatory discontent as traditional weavers saw their livelihoods threatened by technology. Aged thirteen, James Bullough may have witnessed the notorious Luddite riots which swept Lancashire and Yorkshire in 1812. Now seen as a marked man, accelerating the pace of change, his position was precarious, but his drive for new inventions never wavered. His biggest breakthrough came in 1841, with the joint patenting of the Roller Temple and Weft Fork for powerlooms. The effect was dramatic and produced the famous Lancashire loom which, with subsequent modifications, was to remain the workhorse of the weaving industry for over a century. The effect was equally marked in the public outrage it caused. Employers were threatened with violence and walkouts by their workers if they showed any interest in the ‘professed improvement of the loom, introduced at the Brookhouse Mills in Blackburn’.

Another depression had set in, and such was the hostility to innovation in the streets that, for at least the second time in his life, James had to flee Blackburn for his personal safety. The troubles continued and reached a climax in August 1842, when 700 Special Constables failed to prevent crowds storming one mill after another, destroying boiler plugs and rendering the weaving machines useless. This incident entered history as the Plug-Drawing Riots. Bullough’s Brookhouse Mill was specifically targeted and another petition was brandished by protestors, denouncing the Lancashire loom for which ‘the patent was considered to be an evil in all its bearings’. Not that he knew it then, but this was the last major resistance the indomitable James Bullough had to face. Thereafter the populace was forced to move to the inevitable quickstep of change.

In 1845 James ended fifteen years at Brookhouse and moved on to other mill-owning partnerships in Oswaldtwistle, Water-side and then Baxenden. Now trading as James Bullough & Son,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.5.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Beruf / Finanzen / Recht / Wirtschaft ► Wirtschaft | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85790-052-8 / 0857900528 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85790-052-4 / 9780857900524 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich