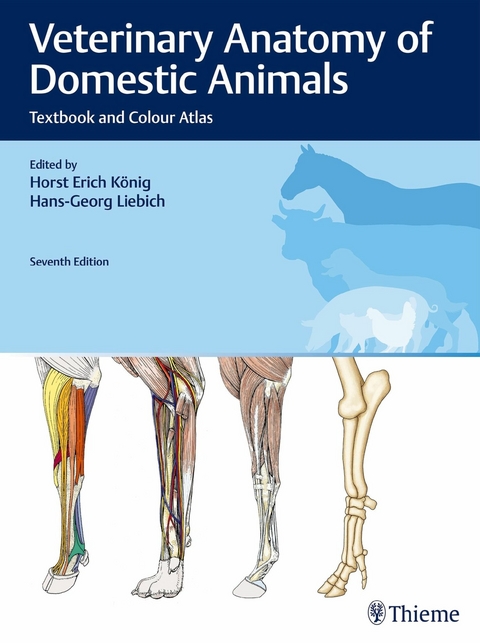

Veterinary Anatomy of Domestic Animals (eBook)

Thieme (Verlag)

978-3-13-242935-2 (ISBN)

1 Introduction and general anatomy

H.-G. Liebich, G. Forstenpointner and H. E. König

1.1 History of veterinary anatomy

G. Forstenpointner

The doctrine of morphology as the scientific study of the form and structure of organisms was founded by Aristotle. He defined morphology as the search for a common construction plan for all structures, while adhering to a strict methodological process. Where similarities can be found, the relation between form and function requires further clarification. This scientific approach set Plato’s best student apart from the early Greek natural philosophers and to this day is the principle method employed in all areas of basic research.

Presumably Aristotle performed anatomical research through dissections. References found in his work Historia Animalium indicate that he published another treatise, Parts of Animals, which sadly did not survive. This work dealt mainly with the digestive and reproductive systems. Here Aristotle recorded his impressions with schematic illustrations. Many of his observations were naturally incomplete, which often led him to erroneous conclusions. However, many of his thoughts on function remain worth reading: for example, his explanation of quadruped locomotion recorded in The Gait of Animals. Being a teacher, Aristotle’s greatest motivation for research was gaining knowledge for knowledge’s sake. This motivation was carried on by his student, Theophrastos of Eresos, and by Roman researchers in natural science such as Plinius and Aelian.

Almost two thousand years passed before the humanists of the 15th and 16th centuries renewed the Aristotelan access to comperative morphology. Especially in Italy, the study of animal and human bodies led to many new discoveries in this field. These findings were meticulously recorded in a demandingly artistic manner and are today famous works of art.

Leonardo de Vinci, by far the most famous artist of this period, embodied this new quest for knowledge and understanding, as is evidenced in his multifaceted research.

Other excellent researchers were Fabrizio d’Acquapendente, who completed the first work in comparative embryology (De formatu foetu, 1600), and Marcello Malpighi, who studied the development of the chick embryo (Opera omnia, 1687). Even though initial progress was impeded by an unstable political situation as well as by the religious establishment, these scientists were forerunners in their fields and heralded in a golden age of comparative anatomy. This trend continued until the end of the 19th century and was characterised by a period of extraordinary productivity of many notable naturalists.

Richard Owen, a renowned English anatomist, and the Germans Johann Friedrich Meckel and Caspar Friedrich Wolff played dominant roles in the resurgence of comparative anatomy as a discipline in Europe. Since the turn of the 20th century, the field of zoological research has been subject to constant redirection. This has led to the development of new disciplines which abandoned the orginal intentions of comparative anatomy as intended by its founders.

Anatomical knowledge is not achied for its own sake, but is a prerequisite for successful medical practice. Throughout the ages, due to religious and ethical boundaries, human dissections were highly restricted or forbidden outright. Recorded exceptions were seldom, one being from the Hellenic school of Alexandria under the leadership of Herophilus and Erasistratos. These vivisections on criminal convicted contributed to a greater understanding of neuroanatomy. Furthermore, Aristotle’s singular work on human anatomy was drawn from the dissection of a miscarried foetus.

Since animal dissections were the only possibility of studying the principles of form and function, these findings were extrapolated to human anatomy. Claudius Galenus, who served under the Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, became the most famous and influential doctor in Rome.

The results and interpretation which he gained through consequent research laid the unchallenged foundation of anatomical knowledge that lasted throughout the following 1500 years. Galen considered himself a physician by trade, however his understanding of anatomy and physiology was based upon Aristotle’s publications, such as The nature of Things. He ardently pursued research in these two disciplines Aristotle’s methodology. Because Galen’s teachings were intelligible and rational, they endured as the unchallenged foundation of anatomical and physiological knowledge for over 1500 years.

Even though his anatomical conclusions were sound, Galen’s interpretations of some systems, such as the heart and large vessels, were erroneous. Due to the lack of human autopsies, Galen’s extrapolations of animal dissection results were often misguided. For example, he suspected that the Rete mirabile epidurale would also be found in humans even though now we know it is a typical structure of ruminants. Further, he concluded that humans must have a caecum built like that of herbivores or a uterus with cotyledons.

In the tradition of Galen, an anatomical atlas of the pig (Anatomia porci, written by Copho or Kopho) was published in Salerno around 1100–1150. This was not the first anatomy book in veterinary medicine, but rather was meant as an anatomical teaching tool for students of human medicine. The generally accepted myth then and today – that the pig resembles the human more than any other animal – relies greatly on the similar eating habits and the availability of subject material in those days.

During the Renaissance, anatomical studies on human corpses were no longer taboo. With his monumental work on human anatomy (De humani corporis fabrica, 1543), Andreas Vesalius marked the hesitant beginning of a revolutionary new attitude toward the human body. Early anatomists still considered themselves naturalists, compiling many fundamental discoveries of morphology through continuing studies of animal anatomy. Vesalius was the first to realize that the Rete mirabile epidurale represented a typical structure of ruminants. Studies of ruminant digestion were advanced by Johann Conrad Peyer through his magnificent publication in 1685, Merycologia sive de ruminantibus et ruminatione commentarius ( ▶ Fig. 1.1). His discovery of lymphatic tissue (Lymphonoduli aggregati) in the intestinal mucosa resulted in the name Peyer’s patches. From the beginning, the study of comparative anatomy has remained a domain for research institutes specialising in human anatomy, even more so as zoological research turned away from the study of morphology.

Fig. 1.1 Cover of Merycologia.

(Johann Konrad Peyer, Basel, 1685)

Fig. 1.2 Early illustration of the blood vessels of the horse.

(Seifert von Tennecker, pseudonym Valentin Trichter, 1757)

In the last decades of the 20th century, the use of laboratory animals led to the optimizing of therapeutic approaches. The implementation of experimental concepts has been possible only through the application of necessary basic animal morphology, which has largely been provided by physicians. Interestingly, still today animals are chosen as models, not because of their morphological comparability, but rather for their availability.

Veterinary anatomy as a prerequisite for practicing veterinary medicine has developed only in the last few centuries as an independent teaching and research subject. It is evident through ancient and medieval texts for animal caretakers that the anatomical knowledge, especially of horses, was more or less precise ( ▶ Fig. 1.2). However, the systematic portrayal of the basic morphological associations was nonexistent.

Equerry handbooks created in the tradition of Jordanus Ruffus in the late middle ages and early modern age were not systematically organised. They did contain information on equine anatomy, which was often accompanied by ineffectual illustrations. In 1598, Carlo Ruini published an at that time exceptional handbook, Dell’ Anatomia e dell’Infirmita del Cavallo ( ▶ Fig. 1.3). Seeming to appear without a forerunner, this textbook was undoubtedly inspired by Vesalius.

Fig. 1.3 Illustration of the equine musculature.

(source: Dell’Anatomia e dell’ Infirmita del Cavallo; Carlo Ruini, Venice, 1598)

Ruini was born into a prosperous family from Bologna and neither worked as an equerry nor was a member of the university. Through excellent private tutors, he developed a passionate interest in the natural sciences and was an enthusiastic equestrian. Although incomplete and sometimes flawed, his seminal work was nevertheless the first comprehensive and systematic portrayal of equine anatomy. The second half of the book concerning equine diseases was largely an indiscriminate recapitulation of much older literature. The magnificence of this publication lies in its illustrative quality, which rivals that of Leonardo da Vinci or Vesalius. Ruini’s textbook was to be republished, plagiarised and translated many times ( ▶ Fig. 1.5).

At the beginning of the 17th century, veterinary anatomy was slowly beginning to enter a renaissance. However, it was not to be until about 150 years later that a veterinary academy was created where...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.1.2020 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Stuttgart |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Veterinärmedizin |

| Schlagworte | anatomical structures • Arthrocentesis • clinical and applied anatomy • Color Atlas • domestic animals • equine endoscopy • general anatomy • house mammals • nervous system • Respiratory System • Sectional anatomy • Textbook • topografical anatomy • Topographical Anatomy • Veterinary Medicine |

| ISBN-10 | 3-13-242935-X / 313242935X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-13-242935-2 / 9783132429352 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 80,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich