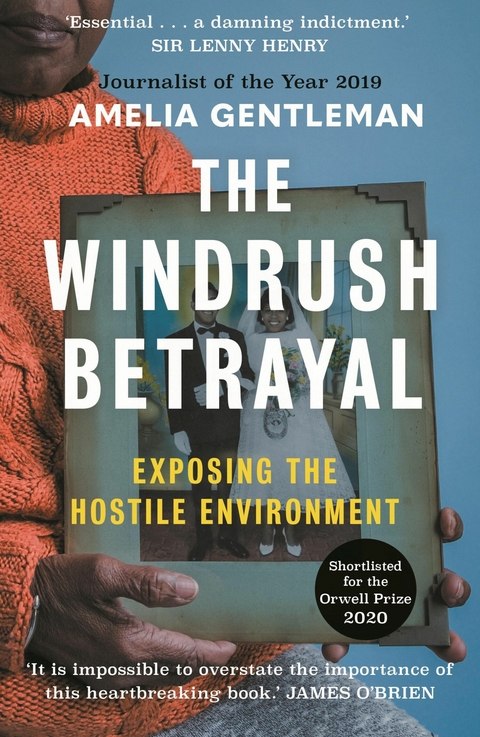

Windrush Betrayal (eBook)

384 Seiten

Guardian Faber Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-78335-186-2 (ISBN)

Amelia Gentleman is a reporter for the Guardian newspaper. She was named journalist of the year (Press Gazette) and won the 2018 Paul Foot journalism award for her reportage on the Windrush scandal, which led to the downfall of the Home Secretary and the government loosening its 'hostile environment' policy for migrants. She has also won the Orwell Prize and Feature Writer of the Year in the British Press Awards. Previously, she was Delhi correspondent for the International Herald Tribune, and Paris and Moscow correspondent for the Guardian. @ameliagentleman

A NEW STATESMAN AND SPECTATOR BOOK OF THE YEARSHORTLISTED FOR THE ORWELL PRIZE FOR POLITICAL WRITINGLONGLISTED FOR THEBAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZEA searing portrait of Britain's hostile environment by the journalist behind the Windrush expose. 'A timely reminder of what truly great journalists can achieve.'DAVID OLUSOGA'[Gentleman's] reporting proves why an independent press is so vital.'RENI EDDO-LODGE'A book that keeps you informed and makes you angry.'GARY YOUNGE'It is impossible to overstate the importance of this heartbreaking book.'JAMES O'BRIENHow do you pack for a one-way journey back to a country you left when you were eleven and have not visited for fifty years?Amelia Gentleman's expose of the Windrush scandal - where thousands of British citizens were wrongly classified as illegal immigrants with life-shattering consequences - shocked the nation and led to the resignation of Amber Rudd as Home Secretary. Here, Gentleman tells the full story for the first time. 'Essential . . . a damning indictment.'SIR LENNY HENRY'Gentleman boldly chronicles the devastating reality of a scandal that illegalised, imbruted and abandoned British citizens.'DAVID LAMMY MP'I'm thankful for the truth and hope [. . .] in Amelia Gentleman's The Windrush Betrayal.'ALI SMITH'A devastating account.'CLAIRE TOMALIN

Should be compulsory reading for all Home Office ministers and civil servants. Immigration lawyers and campaigners also have much to learn. Gentleman writes brilliantly and her very readable book is full of moving portraits of the victims. It is a reminder that Gentleman's ability to collect and then convey these very human and humane stories was absolutely critical to the exposure of the Windrush scandal.

I'm thankful for the truth and the hope.

Campaign journalism at its most urgent.

A devastating account of how British citizens brought to Britain as children by their parents, and who had made their working lives here, were accused of being illegal immigrants, persecuted and forcibly deported. One of the most shameful episodes in our history is revealed, bringing tears for the victims, hurrahs for the author and shame for the government that oversaw the policy.

Gentleman has carefully documented the hell experienced by ordinary citizens caught up in the Tories' 'hostile environment' for illegal immigrants - so carefully that you have to believe the unbelievable.

Shocking... Gentleman recounts the stories of special needs teaching assistants, car mechanics, factory workers, caretakers and ambulance drivers: lives disrupted, people living in fear.

Powerful, disturbing and brilliant.

Untangles the wretched story of how Home Office intransigence and inertia ruined the lives of so many people who were the descendents of the first Windrush generation.

Recounts and exposes some of the most egregious effects of the "hostile environment" approach.

A withering account of what happened when the Conservative party decided, in the words of the then home secretary Theresa May, "to create here in Britain a really hostile environment for illegal migration". If much of this story is familiar that's largely due to Gentleman, whose reporting for the Guardian on this shameful episode saw her named journalist of the year at the 2018 British journalism awards. Gentleman's book contains valuable lessons - about the importance of maintaining paper-based archives, of allowing citizens direct access to officials, and of supporting investigative journalism.

In August 2015, a little over two years before she was detained, Paulette Wilson had received an extremely worrying letter. ‘That was the day my world changed,’ she told me later, an unmistakable Midlands lilt in her voice. On a sheet of paper decorated with the Home Office logo and headed with the words ‘Notice of Immigration Decision’, the letter stated: ‘Paulette Wilson. You are a person with no leave to enter or remain in the United Kingdom.’

Paulette was alone at her flat in Wolverhampton when she opened it; she skimmed through the document, which was written in clunky and perplexing officialese, to try to understand why she had been sent such a distressing notification. ‘You are specifically considered to be a person who has failed to provide evidence of lawful entry to the United Kingdom,’ it announced. ‘Therefore you are liable for removal.’ This was followed by a warning in alarming capitals: ‘LIABILITY FOR REMOVAL’. ‘If you do not leave the United Kingdom as required you will be liable to enforced removal to Jamaica.’

‘Removal’ is the gentler official term for deportation, a word which is technically used only when a criminal is being sent out of the country; but beyond Home Office employees, few people understand the distinction, and most view a forced expulsion from the country, often with handcuffs used, as deportation, regardless of whether this is the correct terminology.

The document upset Paulette profoundly, shaking her sense of who she was. After a lifetime in England, she had always assumed she was British and had never had any reason to question her identity. This sudden official challenge to her status was as horrific as it was surprising. ‘It made me feel like I didn’t exist.’ Uncertain how to respond to the letter, she stuffed it in a drawer so she wouldn’t have to look at it, hiding it alongside another mystifying notification she had received the week before from the Department for Work and Pensions which stated that she was no longer entitled to any financial support because her immigration status was unclear. She mentioned the letters to no one. ‘I was panicking. I was too scared to tell my daughter. I didn’t know why they wanted to get rid of me.’

In the days that followed, Paulette’s thirty-nine-year-old daughter Natalie noticed that her mother was behaving extremely oddly. Normally very bubbly and cheerful, Paulette had withdrawn into herself. It was a while before Paulette steeled herself to show Natalie the Home Office letter. Natalie was as confused as her mother had been, and had to read it several times.

You have no lawful basis to remain in the UK and you should leave as soon as possible. By remaining here without lawful basis you may be prosecuted for an offence under the Immigration Act 1971, the penalty for which is a fine and/or up to 6 months imprisonment. You are also liable to be removed from the UK. If you do not leave voluntarily and removal action is required you may face a reentry ban of up to 10 years. If you decide to stay then your life in the UK will become increasingly more difficult.

A list followed explaining that anyone who employed Paulette would face a £20,000 fine, that her landlord would be fined for failing to spot her irregular immigration status, and that she could be charged for NHS treatment.

Natalie knew that her mother had arrived in England as a child and had never left the country, but her first instinct was to feel annoyed with Paulette for having failed to be upfront with her.

‘Mum, are you an illegal immigrant?’ she asked, aghast and angry. ‘All this time, and you haven’t told me?’

‘I didn’t know,’ Paulette replied. Her evident distress and confusion convinced Natalie that this was as shocking and new to Paulette as it was to her.

Natalie, who works part time as a dinner lady at the local primary school, embarked on a heroic but ultimately futile two-year campaign to persuade the Home Office that a bureaucratic error had resulted in her mother being misclassified as something she was not. Anyone who has tried to take on the Home Office will know that it is an unequal battle, with confused and frightened individuals spending hours held in automated telephone queuing systems, waiting to speak to government employees who read from scripts and have scant discretion to listen or to divulge any helpful information.

Initially, all Natalie was able to understand was that Paulette needed to start making regular trips to a Home Office reporting centre twenty-four miles away in Solihull. She had already missed one appointment, after which another terrifying letter arrived informing her that she was ‘liable to detention’ and that if she failed to report again she would be prosecuted under Section 24 (1) (e) of the Immigration Act 1971, which could lead to a prison sentence or a £5,000 fine, or both.

The Home Office letters were written in deliberately frightening language, and I was startled by their menacing tone when Paulette showed them to me during our first meeting in November 2017. She had been released from Yarl’s Wood a few weeks earlier, after a last-minute intervention by her MP, but she had been told that she was still facing deportation. I was shocked by the Home Office’s decision to imprison a grandmother who had spent a lifetime in the UK, and to terrify her with such disturbing warnings. From the moment I heard about her treatment it was clear that a terrible mistake had been made, but I struggled to understand how such a serious error could have happened, why Home Office staff were persisting in threatening her with removal, and why no one had bothered to apologise. I sat for several hours with Paulette in Natalie’s Wolverhampton flat, listening to Paulette’s life story, trying to unravel why she could possibly have been branded an illegal immigrant and scheduled for forced removal from the country she called home.

*

Paulette travelled alone to the UK on a British Overseas Airways Corporation flight from Kingston, Jamaica, some time in 1968. She doesn’t know the precise date because all the adults who were responsible for looking after her then are now dead, and there is no one she can ask. She doesn’t still have her plane ticket (of course) and doesn’t have a diary chronicling this life-changing event (unsurprisingly), and she isn’t even entirely sure if she was eleven or possibly twelve when she arrived. She just knows it was winter and extremely cold when she stepped out of the airport, wrapped up in several aeroplane blankets layered over her skimpy orange dress, and saw England for the first time. Fifty years later, the memory of the icy sensation that hit her when the airport door opened still makes her shudder.

She remembers looking down at the pavement, puzzled by the white stuff scattered on the ground. She turned to her grandparents, Isaiah and Zenika James, who had come to collect her at Manchester airport, and asked: ‘What is all the salt doing outside?’

‘No, Paulette. It’s not salt,’ her grandmother said, producing a woollen coat and boots for her. ‘It’s called snow.’

‘All of a sudden my body started changing colour. I went purple from head to foot. It was that cold,’ she told me.

It had been a confusing twenty-four hours. Her mother had taken her to the airport in Jamaica; she was so overwhelmed by what was happening to her, that she was unable to register fully the significance of the looming permanent separation. Instead she focused on her fear of the beast-like aeroplane that she was going to be travelling on. ‘I’d never seen a plane before. I’d heard them and seen them moving in the sky but I’d never seen one close. It looked like a giant truck that was going to have to fly.’ She doesn’t remember anyone explaining why she was going, she just has a dim recollection that it was accepted unquestioningly that she was leaving her mother in Jamaica so she could have a better life in England.

For much of her early childhood in central Jamaica, Paulette’s grandparents had raised her because her mother had only been seventeen when she was born and not ready to look after her. But Isaiah and Zenika had left to work in England when Paulette was seven or eight. Zenika, in particular, had missed Paulette terribly and had sent money for a plane ticket so her granddaughter could join her.

She was looked after by an air hostess on the flight, someone she remembers being very kind. She thinks this was the first white woman she had ever spoken to. Paulette found it hard to understand her strange accent but eventually realised she was being offered something to eat, so she asked for yam dumplings, which she was sorry to discover were not available. She remembers the BOAC woman retying the ribbons in her hair before they landed, and leading her through the airport to find her relatives.

Her grandparents drove her to their home, on a redbrick, two-storeyed terraced street in Wellington in the Midlands. She was appalled by how dark the new country seemed but excited to find that for the first time in her life she had her own room, with a bed, a dressing table and a wardrobe. Downstairs there was a television, which delighted her because there had been no electricity in her village in Jamaica.

Her new life did not go smoothly. She was very...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.9.2019 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | a hostile environment • amelia gentleman • Black and British • David Olusoga • guardian books • Immigration • Reni Eddo-Lodge • Windrush |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78335-186-1 / 1783351861 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78335-186-2 / 9781783351862 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich