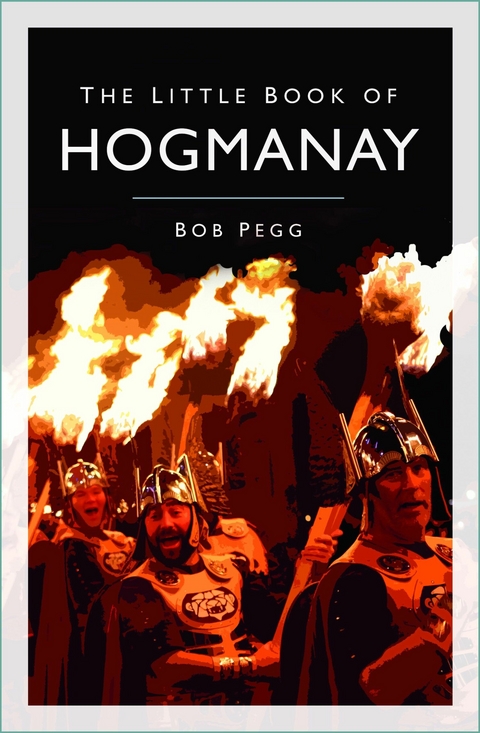

The Little Book of Hogmanay (eBook)

144 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-5153-1 (ISBN)

BOB PEGG began his professional career in 1970 as singer, musician and songwriter with the folk rock band Mr Fox. Later he teamed up with instrumentalist Nick Strutt, and ended the decade as a solo singer-songwriter, with five albums for Transatlantic Records under his belt. In 1989, after a spell as one half of performance duo The Beasties, he moved to the Highlands of Scotland where he now lives, working as a storyteller, writer and musician.

1

THE QUEST FOR HOGMANAY

Hogmana, hoguemennay, hagmenay, hug-me-nay, huigmanay, hagmonick, hangmanay, huggeranohni, hog ma nae; these are some of the configurations used over the past 450 years for that mysterious word we now agree to spell as ‘Hogmanay’. But where does it come from, and what does it mean, with its embodiment of the spirit of the Caledonian New Year’s Eve, when the Scots celebrate with whisky, music, dancing and good cheer, and the rest of the world is very welcome to join in, if it pleases?

Over the last couple of centuries, the origins and meaning of Hogmanay have been discussed at length, but never rooted out. There are just too many possibilities to choose from. With its variety of spellings, the word begins to crop up relatively frequently in the seventeenth century. During the following century, it was scrutinised by a growing body of antiquarians, and John Jamieson’s Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, which was published in two volumes in 1808 and 1809 – the dictionary itself a great feat of antiquarian scholarship – gives the meaning of ‘Hogmanay’ or ‘Hogmenay’ as ‘the name appropriated by the vulgar to the last day of the year’. Jamieson adds that, in Northumberland, the month of December is called ‘Hagmana’, quotes from a late seventeenth-century account of ‘plebeians in the South of Scotland’ going about ‘from door to door on New-year’s Eve, crying Hagmane’, and gives a further meaning as a New Year’s Eve gift or entertainment. Jamieson then goes on to suggest possible origins of the word, from the Scandinavian ‘Hoggu-not’ or ‘Hogenaf’ – a Yule Eve night of animal slaughter – to the French ‘Au gui menez’, translated as ‘to the mistletoe’, a cry uttered in the sixteenth century by participants in the Fête de Fous (or Feast of Fools), a midwinter period of license and satirical mockery. Jamieson quotes from an article published in the Caledonian Mercury on 2 January 1792, which says that:

… many complaints were made to the Gallic Synods, of great excesses which were committed on the last night of the year, and on the first of January, during the Fête de Fous, by companies of both sexes, dressed in fantastic habits, who run about with their Christmas Boxes, called Tire Lire, begging for the lady in the straw, both money and wassels. These beggars were called Bachelettes, Guisards; and their chief Rollet Follet. They came into the churches, during the service of the vigils, and disturbed the devotions by their cries of Au gui menez, Rollet Follet, Au gui menez, tiri liri, mainte du blanc et point du bis …

The derivations that Jamieson suggests are still offered today when the origins of the meaning of Hogmanay are discussed, and no scholar during the two centuries since his time has come up with a more plausible alternative; though a charming suggestion was made by John MacTaggart in The Scottish Gallovidian Encyclopaedia (1824). MacTaggart, from Kirkcudbrightshire, a farmer’s son, only in his mid-twenties and largely self-educated, cheekily comments on John Jamieson’s labours:

HOG-MA-NAY, or HUG-ME-NAY – The last day of the year. Dr. Jamieson, with a research that would have frightened even a Murray or a Scalinger to engage in, has at last owned, like a worthy honest man as he is, that the origin of this term is quite uncertain; and so should I say also, did I not like to be throwing out a hint now and then on various things, even suppose I be laughed at for doing so.

Then here I give, like myself, whom am a being of small scholarcraft, a few hindish speculations respecting this mystic phrase; to be plain, I think hog-ma-nay means hug-me-now – Hawse and ney, the old nurse term, meaning, ‘kiss me, and I’m pleased,’ runs somewhat near it: ney or nay may be a variation that time has made on now. Kissing, long ago, was a thing much more common than at present. People, in the days gone by, saluted [each] other in churches, according to Scripture, with holy kisses; and this smacking system was only laid aside when priests began to see that it was not holiness alone prompted their congregations to hold up their gabs to one another like Amous dishes as Burns says …

At weddings too, what a kissing there was; and even to this day, at these occasions much of it goes on: and on the happy nights of hog-ma-nay, the kissing trade is extremely brisk, particularly in Auld Reekie [Edinburgh]; then the lasses must kiss with all the stranger lads they meet …

From such causes, methinks, hog-ma-nay has started. The hugging day the time to hug-me-now.

Perhaps in a similar spirit of mischief, Professor Ted Cowan, in an article in The Scotsman in 2005, proposes ‘houghmagandie’ – coolly defined in The Concise Scots Dictionary as ‘fornication’ – as at least a close relation, given the amount of kissing and general emotional warmth that the season generates.

Whatever the truth about the origins of Hogmanay – and what a splendid word it is, whatever its derivation – the links to the French Fête de Fous may be real enough, given the cultural closeness of France and Scotland during the Auld Alliance (1295–1560). Before the Reformation in Scotland, the Christmas – or Yule – period lasted from Christmas Eve or before until Twelfth Night and beyond. As in France and elsewhere, what in some parts of Scotland came to be called the Daft Days was a time when less inhibited folk would don disguises, cross-dress, and roam the streets singing, playing music, larking about, and generally making a racket.

In 1651 Oliver Cromwell, who was then occupying Edinburgh, had the English Parliament ban Christmas. In Scotland, however, the Reformed Church, on the look-out for anything that smacked of Catholic ‘superstition’, had already abolished all feast and saints’ days in their First Book of Discipline of 1560 on the grounds that they had no scriptural authority. This didn’t, however, stop folk celebrating Midwinter in ways which had nothing to do with Christianity of any stripe. On 30 December 1598, Elgin Kirk Session records:

George Kay accusit of dancing and guysing in the night on Monday last. He confesses he had his sister’s coat upon him and the rest that were with him had claythis dammaskit about thame and their faces blackit, and they had a lad play upon banis [bones] and bells with them. Arche Hay had a faise [mask] about his loynes and a kerche about his face. Ordained to make repentance two Sundays bairfut and bairleggit.

The following year:

Anent the Chanonrie Kirk. All prophane pastime inhibited to be usit be any persones ather within the burgh or college and speciallie futballing through the toun, snaw balling, singing of carrellis or uther prophane sangis, guysing, pyping, violing, and dansing and speciallie all thir above spect. forbidden in the Chanonrie Kirk or Kirk yard thairoff (except football). All women and lassis forbiddin to haunt or resort thair under the paynis of publict repentans, at the leist during this tyme quhilk is superstitiouslie keipitt fra the xxv day of December to the last day of Januar nixt thairefter.

Cross-dressing and disguise, street games, music, singing and dancing in the streets after dark are all aspects of the Scottish midwinter celebrations that the Church failed to suppress. Many of them have kept going, or, have faded out and then been revived, into the present day. But although the festivities of the Yule period did continue in some areas, the effect of banning Christmas and its associated customs and pastimes was to shift many of these activities to the New Year.

A switch to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 put New Year back eleven, and then twelve days. Many people felt aggrieved that they had been robbed of these days, and some communities continued to celebrate Christmas and New Year in the Old Style, eleven or twelve days later than their modernised neighbours. In 1883, Constance Gordon Cumming writes:

There is a further division of the winter festivals by the partial adoption of New Style in reckoning. Thus, just as one half of the people keep Hallowe-en on the last night of October and the others observe the 11th of November, so with the New Year. This is especially remarkable on the Inverness-shire and Ross-shire coasts, which face one another on either side of the Beauly Firth. Long before sunrise on the first of January, the Inverness hills are crowned with bonfires and, when they burn low, the lads and lassies dance round them and trample out the dying embers. The opposite coast shows no such fires till the morning of the New Year Old Style, when it likewise awakens before daylight to greet the rising sun.

The Ross-shire Journal for 4 January 1878 describes the success of local businessmen in persuading the citizens of Alness to observe calendrical changes made over 100 years previously:

Yesterday was observed by all as the New Year holiday. Even conservative Bridgend went heartily in for it. Mr MacKenzie, ironmonger, and Mr Munro, merchant, had visited every house in the town last week and explained to the people the absurdity of observing the 12th of January. All pledged themselves to holding the 1st and it happened as promised.

But the following year, on 8 January 1879, The Ross-shire published a mild reproof to those folk in Tain who were still holding on to the old ways:

A great many of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.9.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Spielen / Raten | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Sonstiges ► Geschenkbücher | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie ► Volkskunde | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Auld lang syne • black bun • Customs • Festival • first-footing • Folklore • history of hogmanay • history of hogmanay, folklore, tales, customs, traditions, hogmanay food, hogmanay drink, pagan celebration, hogmanay celebrations, festival, new year, scotland, first-footing, shortbread, whisky, black bun, auld lang syne, robert burns, rabbie burns, scottish history, scottish festival, scottish traditions • history of hogmanay, folklore, tales, customs, traditions, hogmanay food, hogmanay drink, pagan celebration, hogmanay celebrations, festival, new year, scotland, first-footing, shortbread, whisky, black bun, auld lang syne, robert burns, rabbie burns, scottish history, scottish festival, scottish traditions, lbo hogmanay • hogmanay celebrations • hogmanay drink • hogmanay food • lbo hogmanay • New Year • pagan celebration • rabbie burns • Robert Burns • Scotland • scottish festival • Scottish History • Scottish traditions • Shortbread • Tales • Traditions • Whisky |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-5153-2 / 0750951532 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-5153-1 / 9780750951531 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich