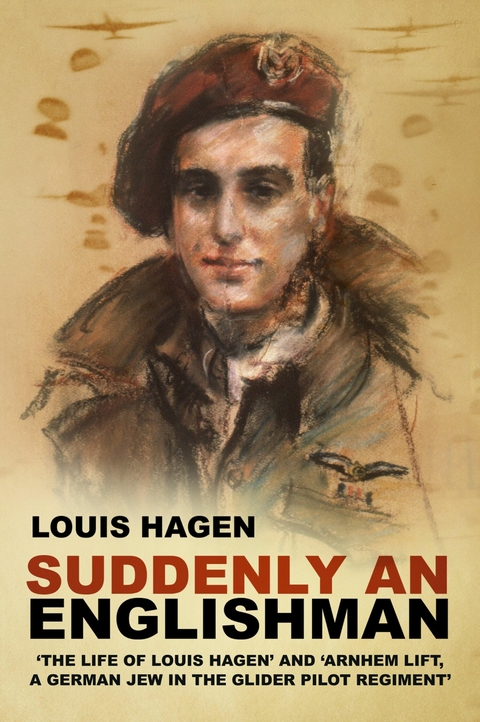

Suddenly an Englishman (eBook)

306 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-720-9 (ISBN)

LOUIS HAGEN (1916-2000), born into a Jewish banking family, was sent to a concentration camp for writing an anti-Nazi joke on a postcard. A high-ranking Nazi judge and friend of the family got him out and he escaped to England, where he became a glider pilot, fighting for the British at Arnhem. He was the author of several books, including Ein volk, ein Reich, and went on to be a successful journalist and film producer. Caroline Hagen-Hall, his daughter, has edited his unpublished autobiography.

'England is my home, and if someone asks me what I am - German, Norwegian, Jewish or British - I answer, "e;I'm an Englishman."e;'In 1934, aged just 16, Louis Hagen was sent to Lichtenberg concentration camp after being betrayed for an off-hand joke by a Nazi-sympathising family maid. Mercifully, his time there was cut short thanks to the intervention of a school friend's father, and he escaped to the UK soon after. 'The Life of Louis Hagen' follows his adventures across the globe and the characters he met along the way, from the founder of the NHS to a Nobel Prize winner to one of the earliest animated-film directors, all told in lively and unflinching detail.Of the 10,000 men who landed at Arnhem, 1,400 were killed and more than 6,000 were captured - a bloody disaster in more ways than one. 'Arnhem Lift' is Hagen's breathtaking and frank account of what it was like in the air and on the ground, including his daring escape from the German Army by swimming the Rhine. Indeed, it was so honest that Hagen found himself banished to India by his shocked commanding officer soon after its initial publication in 1945.Suddenly an Englishman is the complete story of the remarkable Louis Hagen, a German Jew who survived a concentration camp to become a decorated glider pilot in the British Army Air Corps. His first book, Arnhem Lift, was the earliest published account of the Battle of Arnhem while his accompanying autobiography remained unpublished - until now.

Louis Hagen (1916-2000), born into a Jewish banking family, was sent to a concentration camp for writing an anti-Nazi joke on a postcard. A high-ranking Nazi judge and friend of the family got him out and he escaped to England, where he became a glider pilot, fighting for the British at Arnhem. He was the author of several books, including Ein volk, ein Reich, and went on to be a successful journalist and film producer. Caroline Hagen-Hall, his daughter, has edited his unpublished autobiography.

4

Schloss Lichtenberg

As the Nazis came to power, our happy, close-knit family life came under threat. I had always known about my family’s Jewish background but had never thought much about it. We were like all the other families in Potsdam: German. Our family had lived in the country for hundreds of years and my father had been awarded the Iron Cross (Second Class) for his service as a German naval officer. We never knew this until after his death, when I found it tucked away among his less important bits and pieces.

Gradually, I was made more aware of my Jewishness, at first through antisemitic propaganda in the newspapers and on the radio. Our friends remained our friends and our acquaintances assumed we were fellow members of the master race – we did not look particularly Jewish, and certainly nothing like the crude cartoons in Der Stürmer and other Nazi publications – but it was not long before I began to feel like an outsider. I was expelled from the rowing club, excluded from dances and public functions and was made to feel like a criminal if I tried to take out an Aryan girl. I was constantly reminded that, in the opinion of the new German political system, I was a second-class citizen; but even then I felt, as my father did, that this squalid madness could not possibly last.

It did last, and in May 1934 I was arrested by the Brownshirts (SA) and sent to the concentration camp of Schloss Lichtenberg near Torgau.

The year before, I had written a postcard to my sister Carla: ‘Toilet paper is now forbidden, so there are even more Brownshirts.’ This pathetic schoolboy joke had been intercepted by a maid. When my mother later caught her stealing jewellery and sacked her, she triumphantly showed my mother the postcard, which she had kept for just such an occasion. She told my parents she would denounce me to her boyfriend in the SS if they did not reinstate her.

It was an agonising decision for them. They talked it over at length, and in the end, decided they must not allow themselves to be blackmailed. Of course, they could not have imagined what the consequences would be for me. Who would believe a teenage boy could be arrested and taken to a concentration camp for a childish joke?

But one beautiful summer morning, two policemen came to the BMW factory at Eisenach, where I was working as an apprentice, and arrested me. At the police station, they emptied my pockets, took down my personal details, and locked me up for the night. They were vague about the reason for my arrest; a uniformed Nazi storm trooper who came to interrogate me next day told me only that it was ‘political’.

For the next few days, I was shunted around by train to different small-town police stations, where I was endlessly interrogated by obviously amateur, pompous Nazi Party members who took copious notes. The interrogations were unpleasant, with verbal abuse, threats, and spotlights glaring down at me, but I was never physically hurt. I feel sure the reason for this was that the sessions took place in police stations, and the police at the time still believed in protecting the rights of the individual – until found guilty in a court of law. Neither I nor any of my family had ever belonged to a political party or attended a political rally; my only crime was that I was 100 per cent ‘non-Aryan’.

As my journey continued, I was joined by more prisoners until there were about twenty of us: Jews, dissidents, Catholics, communists, and pacifists. We talked very little among ourselves because we were all afraid of informers.

Eventually, we arrived at our final destination, Schloss Lichtenberg, less than an hour’s drive from my home in Potsdam. The Schloss was not so much a castle as a fortified, rather dilapidated farm, newly painted bright yellow. Fifty of us were housed in the large grain and haylofts, sleeping on rough palliasses on the floor. There was one water tap and a basin, which the older men used to pee in when they could not wait.

In the middle of the night, the younger prisoners were often woken by drunken guards and taken to their mess. There, to howls of laughter, we were ordered to pull down our trousers and pants and get on all fours. Then they took turns to slap our naked bottoms, either by hand or with little riding whips, which they kept tucked away in their jackboots. I had the impression I was often singled out for special attention because of my youth and class. As they beat and abused me, they called me a spoilt Yiddish brat crying for his fat Yiddish mama. They would teach me a lesson; they would show me who was master in Germany today.

They made fun of my uncircumcised penis. ‘How typical of your race,’ they jeered, ‘to go to such lengths to deceive us.’

More often than not, these sessions happened over the weekend. It was their idea of a bit of fun to round off a good night out.

Some of them obviously felt sorry for us and tried, without much success, to restrain the others when they began to get frenzied and draw blood. There was one very blond and good-looking youth, not much older than myself, who tried to make his mates go easy on me by pretending to join in the spirit of the occasion. ‘That’s enough. Let the poor bastard go. Can’t you see his Jewish arsehole is already bleeding? We don’t want it to get infected.’

Sometimes he managed to slip me out and lead me back to my quarters, putting an arm around my shoulders and mumbling drunkenly, ‘Don’t mind them. They’re good chaps at heart, just a little drunk.’ I had a hard time not leaning on his shoulder and pouring out my misery and frustration. But I always blinked back the tears; I dared not show weakness or gratitude. He was a degree or so better than the others, but he wore the same brown uniform and jackboots. When he left, I fell back on my sack of straw and cried uncontrollably. I was comforted by a fat, middle-aged communist called Wolfgang, who became my friend.

One day, while I was playing chess with Wolfgang, I noticed a group of men crowding around the window facing the courtyard. We got up to see what they were looking at, but before I could get there, Wolfgang pulled me back. ‘There’s nothing there, Büdi,’ he said. ‘Let’s get on with the game.’ But I insisted on seeing what was happening. If ever I got out, I wanted to be able to tell people what was going on. It turned out to be the cruellest, most shocking thing I have ever seen.

It was a very hot sunny day. A group of SA men in their shirtsleeves were standing round the farmyard pond, where there were usually a few ducks swimming and a couple of pigs cooling themselves in the mud. That day there were neither ducks nor pigs in the pond, but instead, four prisoners splashing around, entirely covered in mud, moving as if in slow motion because of its dragging weight. They were trying to crawl out of the pond, but whenever they reached the edge, the SA men kicked them back in, laughing and shouting. I could not go on watching and turned away. Later, I learnt that none of them survived.

When the guards could think of nothing better to do, they gave each of us a bucket of water, then chased us around the courtyard. If we spilt any, they beat us. I was young and very fit, and I managed well enough, but some of the older men were soon exhausted in the blistering heat and collapsed. They were then kicked and beaten until they got up and started running again. The weakest were chased into the muddy pond to ‘cool down’ before, covered in mud, they had to start running again.

Perhaps because I was the youngest and the son of a well-known banker, I was chosen for the duty of emptying the latrines. They were made from thick wooden planks, about 4m long and 1m wide, and very heavy, so that four people could only just lift one when it was full. We had no spades or tools, so had to empty them with our bare hands. The iron handles of the boxes cut into our palms, which soon became infected; the pain increased each time we were made to do it.

One day, as we were standing miserably to attention in the castle’s courtyard, the gates opened to let in a big black Mercedes flying the Nazi flag. I knew the smartly uniformed man who stepped out; he was Judge Engelman, the father of one of my school friends and a senior civil servant in Potsdam. I heard him say he had come for me, but I did not dare move. I was taken to the commandant in the guard-house, who told me that if I ever revealed to anyone what went on inside the camp, they would ‘get me’, wherever I was, and then I would never ‘get out’. He handed me a statement to sign, acknowledging that I had been well treated and that all my possessions had been returned to me. I signed it.

Once in the Mercedes, the judge turned to me. ‘Now, what happened?’ he asked. I wanted to tell him everything, but I hesitated. I was afraid the two SA men in the front of the car could hear through the glass partition, and I hardly knew my rescuer. I had met him only once at a school function, and he was a prominent member of the Nazi Party, having joined when it still seemed to many conservatives that it represented new hope for Germany. But I remembered those still in prison and knew that I had to take the risk, so I showed him my hands. I don’t think I would have dared to do that today, now we know the full extent of the horrors that were committed by the Nazis.

It was time for me to leave Germany. My older brother and sister had already left, KV for New York and Nina for Paris, and Herr Popp (Generaldirektor (managing director)) had been obliged to sack...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1930s • 1940s • Arnhem • arnhem lift • Auschwitz • concentration camps • german jew • glider pilot • Holocaust • louis hagen • louisi hagen • Nazi Germany • Rhine • Second World War • war autobiography • war correspondant • war journalist • war memoir • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-720-6 / 1803997206 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-720-9 / 9781803997209 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 31,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich