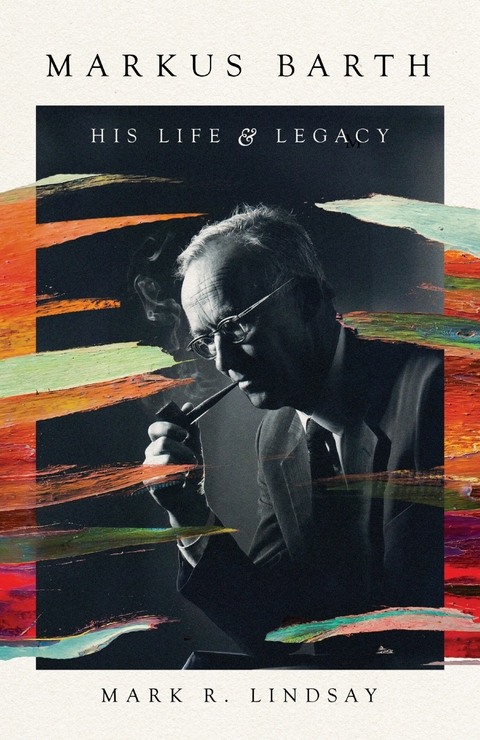

Markus Barth (eBook)

296 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0163-9 (ISBN)

Mark R. Lindsay (PhD, University of Western Australia) is Joan F. W. Munro Professor of Historical Theology at Trinity College Theological School at the University of Divinity in Melbourne, Australia. He is the author of Reading Auschwitz with Barth; Barth, Israel and Jesus; and Covenanted Solidarity.

Mark R. Lindsay is Joan F. W. Munro Professor of Historical Theology at Trinity College Theological School, the University of Divinity. He is the author of Reading Auschwitz with Barth; Barth, Israel and Jesus; and Covenanted Solidarity.

2

“YOU CAN STILL LEARN SOMETHING FROM SOMETHING FALSE”

The Student Years, 1930–1939

THE BARTHS STAYED IN MÜNSTER for almost exactly four years. In March 1930, they were on the move again, this time in response to Karl’s call to a professorship in systematic theology at Bonn. For the next five years, the family lived in a “stately house” at Siebengebirgstraße 18. It may indeed have been imposing; indeed, it was large enough to host as many as eighty-eight people who came to one of Karl’s regular “open evenings” (offenen Abends).1 However, the house was not quite so conveniently located as their previous homes had been, lying on the opposite side of the Rhine—and a good ten kilometers—from both the University, where Karl now worked, and the Beethoven-Gymnasium, where Markus was enrolled to complete his schooling.

In any case, Markus’s mother did not have much time to enjoy it. Within a month of arriving in their new home, Nelly fell ill with chest pains and traveled alone to the Bergisches Land region for recuperation. Charlotte—whose letters most likely did very little to ease Nelly’s angina—wrote to keep her in touch with events at home. Matthias’s injured foot, she reported, was “much better”; meanwhile, Markus and Franziska had again made good use of their bicycles to explore the nearby Siebengebirge.2 Indeed, all five children evidently adjusted to life in Bonn quickly. In May, Nelly told her mother that Hans Jakob was “flourishing and sparkling”; Matthias was either devouring books or building models with his Meccano set;3 while Christoph and Markus were enjoying cycling to school and resuming their piano lessons.4 Even Franziska—by now nearing the end of her schooling—had settled in well to the new routines and was finding lessons (even Latin!) easy.5

That the children had been able to adapt so easily is remarkable given the turmoil and tension in the family home. Quite aside from the busyness and demands of Karl’s new appointment, the move to Bonn coincided with a fresh round of animosity between Nelly, Karl, and Charlotte. It also coincided, perhaps not surprisingly, with the first of Nelly’s demands for a divorce.6 Throughout this time, notes Stephen Plant, Nelly’s family—in particular her mother, Anna—sought to bring the situation to a head, reckoning it to be both unsustainable and intolerable, not least for Nelly’s health.7 The situation was so tense that by August 1930, barely five months after their arrival, Nelly had moved out of their home. “It’s time,” she wrote to Karl’s mother, Anna, “for you to know where I am.” She continued:

Since the day before yesterday I have been staying with [my sister] Anny8, while Hans Jakob has been with my sister Gritti.9 Berti10 is with Matthisli [Matthias] in Stäfa. You have my three big ones with you. . . . I have just written to Karl at the “Bergli” that, until I have learned how to walk this path or another, I must remain alone. I’m not coming to Adelboden, and perhaps also not Bonn. I cannot find the courage, with no new or different inner strength, to return to that existence.11

The very next day, Nelly wrote again to her mother-in-law, this time expressing her belief that Karl and Charlotte would continue on their way together without her (Karl werde mit Lollo ohne mich weiter seinen Weg gehen). Even though she stood “to lose everything,” she felt that she could not continue with the way things were.12

As for Markus, his own maturation continued within this strained and complicated environment. In late March 1931, having previously resisted doing so, Markus was finally confirmed following some much needed “catch-up” catechesis from Karl.13 On Palm Sunday of that year, Nelly traveled with her eldest son to Duisberg—an industrial city about 100 kilometers to the north of Bonn—where superintendent Fritz Horn, a friend of Karl’s, conducted the service. Whether Markus was himself by now fully convinced of the sacramental need for the rite—and, as we shall see, he was later to express grave reservations about it—his confirmation served at least one important practical purpose: it kept open the possibility of theological studies. As Nelly explained to her mother a week before the service, “If he would like to study theology later on, it is a prerequisite.”14

There were other causes for familial celebration too. A year after Karl and Nelly’s separation, Nelly threw a joint birthday party for Christoph and Markus, noting in a letter to her own mother that Karl, too, had been there—alone!15 That Karl was evidently at the party without Charlotte allowed him and Nelly to talk properly for the first time in a long while, about how the situation with Charlotte—what Karl referred to as their “emergency community” (Notgemeinschaft)16—could be endured better on all sides. And perhaps to Nelly’s astonishment—but certainly to her great joy—the party demonstrated that as a family they could be happy together. “Yesterday was so good, so refreshing, once again after a long, long time.” Moreover, “the children also felt it, sitting around the smaller table, only talking Swiss German—it was as intimate as it used to be.”17

At the same time, contentment was able to be found in those parts of family life that were significant precisely because of their normalcy. In April 1932, Charlotte wrote to Nelly—who was, at the time, in Switzerland—of the children’s delight in their own, very ordinary activities: Hans Jakob was cheery, despite a persistent cold; Christoph had (once again) redesigned his bedroom; Markus was happy and planning a solo trip to Paris; and Franziska had, as always, her “joyful plans and intentions.”18

Within this atmosphere, Markus began to find his own way. Just before Christmas 1932, Karl informed Thurneysen of Markus’s most recent exploits: “He has started to move within a circle of . . . Communists, and has been joyfully initiated into the Communist Manifesto, and other secrets of our Soviet future.”19 This political commitment took shape in written form as well. In April 1933, as a seventieth birthday present to his grandmother, Anna Barth-Sartorius, Markus wrote a ten-page booklet titled “Attempts to Solve the Social Questions from the Pre-Marxist Period: A Partial Description of Utopian Socialism Between 1800–1840.”20

Beginning with the claim that any attempt to discern “the nature and aims of socialism” (dem Wesen und dem Ziel des Sozialismus) must start by recognizing that its necessary precondition was the development of modern capitalism,21 Markus continued by explaining to his grandmother how dependent early socialism was on eighteenth-century philosophy. Those first proponents of socialist thought, he said, were indebted to the Enlightenment vision of the perfection and goodness of humankind (die Vollendung und Güte des Menschen) and of the goodness and reasonableness (die Güte und Vernünftigkeit) of God (or nature).22 While Markus recognized that their ideals were frequently at odds with the reality of the world around them—he gives as examples the plight of mine workers in English collieries23—he argued that their philosophic convictions nevertheless compelled them to believe fervently in the inherent goodness of the world “and all its institutions” (Einrichtungen).24 After discussing two specific examples—Robert Owen25 (1771–1858) in England and Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) in France—Markus concluded his paper by comparing the somewhat naive sentiments of those early socialists with the more sophisticated form of socialism advanced by Karl Marx. Despite acknowledging its occasional problems (die marxistiche Lehre an manchen Stellen noch entscheidende Fehler bringt), Markus ended his booklet by arguing that Marx’s teaching had “meant great progress for the development of socialism, and was perhaps the only right thing for the labor movement.”26

This short paper, written when Markus was only seventeen years old, not only paints a fascinating picture of his early political thinking but also illustrates his preparedness to venture into risky territory. In April 1933, precisely at the time when Markus penned these thoughts in Bonn, Adolf Hitler’s newly formed National Socialist government was ramping up its persecution of political enemies, with communists being chief among them. Repressive action against leftist political groups had been commonplace since Hitler’s seizure of power in January but had escalated in violence and scope in the lead-up to the passing of the “Enabling Act” of March 23 and the “Law for the Reconstruction of the Professional Civil Service” of April 7. The former effectively voted the Reichstag—the parliamentary site of democratic governance—out of existence, while the latter removed Jews and political opponents, especially on the left of the ideological spectrum, from the state’s administrative machinery.27 During March and April, ten thousand communists and social democrats had been arrested in Bavaria alone.28 It was, in other words, an acutely dangerous time in Germany in which to express any socialist sympathies;...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.12.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | biblical scholarship • Biography • Christian • Christian theology • Ecumenical • Historical • historical theology • jewish Christian dialogue • Karl • Karl Barth • Life and work of Markus Barth • New Testament Studies • Pastor • pauline epistles • Princeton Theological Seminary • Reformed tradition • Sacrament • Special Collections • Special Collections at Princeton Theological Seminary • Study • Theologian • Theology |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0163-2 / 1514001632 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0163-9 / 9781514001639 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich