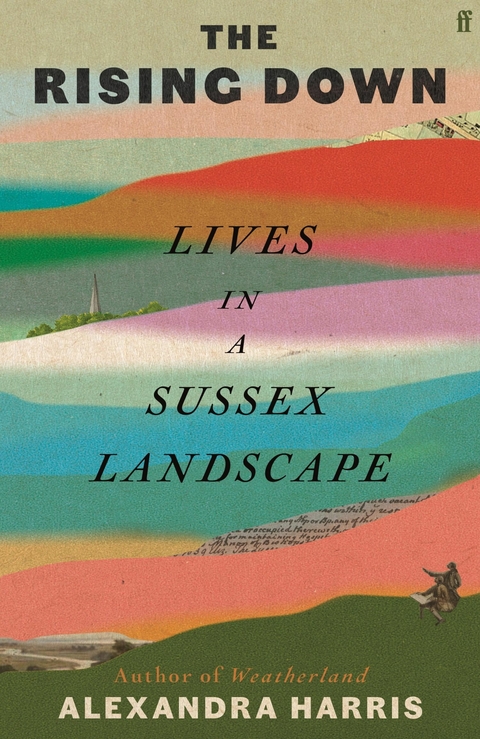

Rising Down (eBook)

408 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-35054-4 (ISBN)

Alexandra Harris is an acclaimed writer, literary critic and cultural historian. She was educated at the University of Oxford and the Courtauld Institute and is now Professor of English at the University of Birmingham. Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper(2010) won the Guardian First Book Award, a Somerset Maugham Award and was shortlisted for the Duff Cooper Prize. Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies (2015) was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize, shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize, adapted for BBC Radio 4 and chosen ten times as a 'Book of the Year'. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, Harris reviews for the Guardian and other newspapers as well as judging literary prizes, writing for exhibition catalogues, working with artists, lecturing widely and speaking on the radio. www.alexandraharris.co.uk 'A joy to read.' Sunday Times 'Breathtaking.' Guardian 'Highly eclectic and original.' Sunday Telegraph 'Hugely ambitious.' TLS 'The wit and wonder of an exceptional literary work.' New Statesman 'An inspiring guide.' Daily Mail

'Remarkable.' THE TIMES'Wonderful.' GUARDIAN'Fascinating.' TELEGRAPH'As a portrait of a place, it's hard to better.' COUNTRY LIFE'A thrill akin to discovering buried treasure.' RICHARD MABEY'Humane, humorous and joyful.' RUTH SCURRWhen the celebrated critic and cultural historian Alexandra Harris returned to her childhood home of West Sussex, she realised that she barely knew the place at all. As she probed beneath the surface, excavating layers of archival records and everyday objects - bringing a lifetime's reading to bear on the place where she started - hundreds of unexpected stories and hypnotic voices emerged from the area's past. Who has stood here, she asks; what did they see?From the painter John Constable and the modernist writer Ford Madox Ford to the lost local women who left little trace, these electrifying encounters - spanning the Downs, Poland, Australia, Canada - inspired her to imagine lives that seemed distant, yet were deeply connected through their shared landscape. By focusing on one small patch of England, Harris finds 'a World in a Grain of Sand' and opens vast new horizons.

Sometimes, when I’m in the midst of other things, marking essays, or listening to friends with a glass of wine getting warmer in my hands, there appears to my mind’s eye a slightly lumpy white surface. It’s the sunlit south wall of Hardham church. I can see it now.

The lumpiness comes from the rubble below the limewash. The church was built from heavy blocks of this and that, sandrock, greensand, flint, each smoothed and shaped as best the men could manage during those months of building a thousand years ago when their arms ached from the mallet and from hoisting up the stones with ropes to lay one course after the next. It’s thought they carried bricks over from the ruins of the Roman posting station, which was a good source of materials in the late eleventh century, even after six hundred years open to the weather. They brought clay tiles too, still mortared together with the lime that had been slathered round them when Britannia was newly conquered. I imagine that the local labourers recruited for the job had known the old and broken walls since they were young; they’d played on Sunday afternoons in a strange tiled pit. They dug out the shiny glazed chips with fingernails and arranged them in new shapes on the ground, or tossed them like knucklebones to be caught on the backs of their hands. Grass grew up between the shards and later cattle were put to graze there, with streams running on three sides of the meadow.

Heringham it was called then, and Heriedehem in the Domesday survey, meaning a settlement of the people of Heregyð, whose name could be shortened to Here. Whoever Here was: a Saxon woman who owned this place and gave her name to it, when women had the right to own land and sell it if they wanted.1 After the stones, perhaps long afterwards, came render and limewash, the native paint of the downs, made with chalk burnt in kilns to form quicklime and slaked with water. Then more layers over the centuries, each one gleaming at first. I like the sheen and the smoothness of this paint over the unseen surface of the stones. But there’s a break in the smoothness: a sharp shadow, lowish down at the chancel end. It’s a gash, reaching almost but not quite through the full thickness of the wall. A violent cut, but carefully made. It was clearly intended to go right through, but has been blocked up on the inside. The recess is painted over in thick white, so that the edges are soft and homely-looking, as if it’s always been here and ought to be here. But it’s not homely. It runs obliquely into the wall, at an angle so odd you have to get up and peer in. It’s sculptural, like a modernist carving; you can enjoy the shape for a moment as you might enjoy one of Ben Nicholson’s abstract constructions made from white and light.

No, this isn’t modernist; it’s eight hundred years old. It forms a slanting shelf on which you can lay your hand, but I’m reluctant to put my hand there. It makes me think of putting a hand through flesh, of Thomas poking his finger into the wound. Many times I’ve stood apprehensively beside this shadowed shelf. It’s common to cut windows in walls, of course, and this is only another sort of window, like the shapely lancets high in the nave. How plain and straight they look by comparison, open-eyed, letting the light in.

This cut in the wall once gave a sightline through to the altar. A simple lean-to construction would have stood on the side of the church, forming the cell in which a holy recluse came to live. From the cell, the slanted window allowed a view of the altar and nothing else. The oddly shaped gash in the white south wall tells us, in the language of windows and stones, about things that happened at Hardham and left no other physical trace.

By 1253 an anchorite was living here, someone who had chosen to be stoppered up, walled in, to worship God on this very spot and see no more of the world than a narrow shadowed room. There’s a record of money being left to this enclosed person, the ‘incluso’, by the Bishop of Chichester, Richard de Wych, who died that year and was later a saint. ‘Item incluso de Heringham dimidiam marcam.’2 Half a mark: enough to register his continuing support of the man sitting upright in his tomb day by day. ‘Incluso’ indicates a male hermit rather than the more common ‘incluse’. Richard remembered too, with the same sum, the ‘incluse de Stopeham’ and the ‘incluse de Hoghton’, the women shut in at Stopham, just a mile or so upstream, and Houghton to the south, where the downs meet the water meadows. When the anchorite died at Hardham, in the cell that was already prepared as his grave, others succeeded him. Fragmentary records suggest that a Prior Robert lived here and died in 1285, bequeathing the cell to a female follower.3 They were all held in place, anchored by the church as a ship might be anchored in a harbour; they also took on the role of anchor and were deeply respected for it, providing the still weight that would fix and shelter the church.

I must have seen this closed window as a girl of ten or eleven. I remember a frisson of shock, but mostly I was pleased to have learnt a new word, ‘squint’, which I stored up among the other architectural words that showed me what to look for in buildings. The wall paintings inside the church were the reason for going to Hardham, and when I lobbied for a family detour in the car from the main road into the little track by the church, the pictures were the attraction. Because we went so infrequently, because years could pass without our entering the little church that stood a mile away from our local chemist and railway station in Pulborough, the paintings were an amazing discovery each time, leaping from the gloom. As for the squint, I didn’t appreciate the physicality of it until much later, when I had read about the lives of anchorites.

The man who came to this spot to surrender the world would have been preparing himself for several years, taking spiritual guidance, living with what he intended to do. As he went about the routine of his days, he carried with him the idea of the cell walls. When he walked down a corridor, he thought of not walking again. He probably lived locally, and may have been one of the Augustinian canons at Hardham Priory just across the fields. In that case he knew the dampness of the place; he knew his skin would be clammy with wet through the winter and the air heavy in his lungs. He knew that each part of his body would protest with aches and fevers.

The priory was spacious and built with graceful craftsmanship. Through the trees, before the land drops down to the river, you can still see the arches, long since made part of a private farmhouse. They rise on slender moulded columns and curve gently to finely carved points. Three portions of blue Sussex sky are framed in quatrefoils. The man, if he was there, thought his way from these upward arches into a tiny room with the door nailed up. He thought of his body chafing at constriction, and then thought of the wall as an extension of his body. He decided that this was what he wanted. A sponsor was sought, someone who would pay for the building of the anchorhold and for an attendant who would prepare basic meals.

Apart from the deep recess of the squint, there is no trace of the cell at Hardham. It is likely that the walls were made from wattle and daub, and reeds cut from the marshes to make a thatched roof sloping up to join the church. Workers pounded at the chancel wall to make the required hole through to the altar. An awkward job: blocks to be pulled out, re-cut, re-inserted. The opening needed to form a funnel, narrowing towards the chancel interior, directed so as to reveal the cross and the Eucharist raised above it. It was a window and a not-window, an anti-window, its eye trained on the circle of the Host. This was the ‘chirche-thurl’. Anchorholds usually had this and one other window, known as the ‘huses thurl’ (the house-hole or parlour-window), positioned on the other side of the cell.4 All transactions with the world had to go through this window. Food and water were passed in, and waste was passed out. Brief conversations were permitted, for example with those who sought religious guidance. But the opening was to be kept curtained at all times.

A Mass was said, the cell blessed. The episcopal seal was laid upon it. Richard of Chichester made the sign of the cross and said the last rites over the body of the man who went in through the one-way door, dust to dust. Tuesday came, Wednesday, and the recluse did not see them. In winter the great yew tree in the churchyard stood out with velvet magnificence.5 It was becoming famous; people said it was so old it had been a sapling in the first flush of new life after the Flood. Three travellers took shelter in its hollow innards one night while the storm dragged at the branches above them. Workers stretched out their legs on the grass in its shade. On a late afternoon in August, a heat haze sat over the fields and the cows moved heavily towards the river. The aching man held himself upright though his muscles had no strength. By the dim light coming through the black curtain, he followed the words of the prayer book.

It was that kind of hot August afternoon when I last went to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-35054-2 / 0571350542 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-35054-4 / 9780571350544 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 15,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich