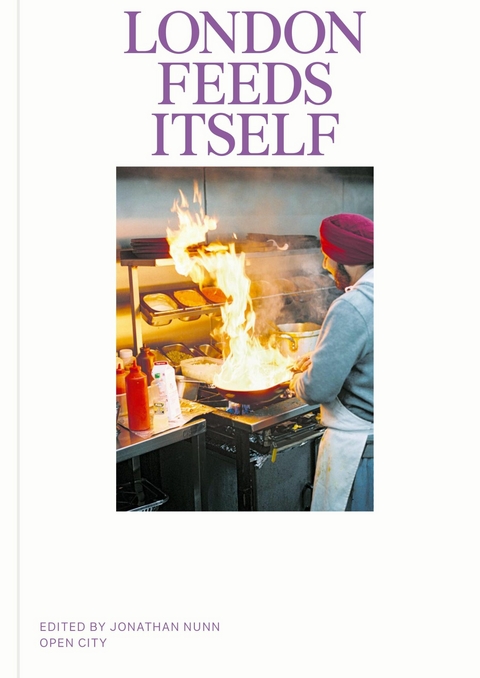

London Feeds Itself (eBook)

280 Seiten

Open City and Fitzcarraldo Editions (Verlag)

978-1-80427-100-1 (ISBN)

Jonathan Nunn is a food and city writer based in London who founded and co-edits the magazine Vittles. He is the editor of London Feeds Itself.

London is often called the best place in the world to eat - a city where a new landmark restaurant opens each day, where vertiginous towers, sprawling food halls and central neighbourhoods contain the cuisines of every country in the world. Yet, this London is not where Londoners usually eat. There is another version of London that exists in its marginal spaces, where food culture flourishes in parks and allotments, in warehouses and industrial estates, along rivers and A-roads, in baths and in libraries. A city where Londoners eat, sell, produce and distribute food every day without fanfare, where its food culture weaves in and out of daily urban existence. In a city of rising rents, of gentrification, and displacement, this new and updated edition of London Feeds Itself, edited by the food writer and editor of Vittles, Jonathan Nunn, shows that the true centres of London food culture can be found in ever more creative uses of space, eked out by the people who make up the city. Its chapters explore the charged intersections between food and modern London's varied urban conditions, from markets and railway arches to places of worship to community centres. 26 essays about 26 different buildings, structures and public amenities in which London's vernacular food culture can be found, seen through the eyes of writers, architects, journalists and politicians all accompanied by over 125 guides to some of the city's best vernacular restaurants across all 33 London boroughs. Contributors: Carla Montemayor, Jenny Lau, Mike Wilson, Claudia Roden, Stephen Buranyi, Rebecca May Johnson, Owen Hatherley, Aditya Chakrabortty, Yvonne Maxwell, Melek Erdal, Sameh Asami, Barclay Bram, Ciaran Thapar, Santiago Peluffo Soneyra, Virginia Hartley, Jess Fagin, Leah Cowan, Ruby Tandoh, Jeremy Corbyn, Dee Woods, Shahed Saleem, Amardeep Singh Dhillon, Zarina Muhammad, Yemisi Aribisala, Nabil Al-Kinani, Sana Badri, Nikesh Shukla.

Jonathan Nunn is a food and city writer based in London who founded and co-edits the magazine Vittles. He is the editor of London Feeds Itself.

London eats itself

The architecture writer Ian Nairn once remarked of Sacred Heart secondary school, just round the corner from where I live in Camberwell, that ‘you can get along from day to day without masterpieces, but you can’t get along without this kind of quiet humanity’. The charity Open City, who published the first edition of this book, has dedicated itself to celebrating the type of buildings that contain within them some kernel of ‘quiet humanity’, the structures that we may not notice because they’re too busy being used and enjoyed by people every day.

When Open City challenged me to edit a book on ‘food and architecture’ I was initially stumped. Is it possible to write a food book about architecture? Or rather, an architecture book about food. The two are not natural bedfellows at first glance, I admit. My initial thoughts on what a ‘food and architecture’ book might look like, in order of when they came to me, were: 1) a kind of urban food systems book, already done so well by writer-architects like Carolyn Steel; 2) something about grand dining rooms, art deco cafes and listed pie and mash shops – the masterpieces – that would please precisely no one; and 3) whatever Jonathan Meades does. Yet ten Owen Hatherley books and a quick glance at the Wikipedia entry on architecture later, I realised that everything about London and food that interests me fits into this seemingly niche intersection: the way that Burgess Park transforms into a Latin fiesta every summer, the specialist food businesses incubated by the nowhere-ness of the North Circular Road, the ability of London’s industrial estates to become nature’s food halls. It turned out that ‘food and architecture’ was, to borrow a phrase from Leytonstone boy Alfred Hitchcock, a MacGuffin. Instead, this is a book about London and its quiet humanity, told through the people and places that feed us.

The framing of London Feeds Itself is 26 chapters about 26 different buildings, structures and public amenities in which various aspects of London’s everyday food culture can be found. There are many versions of London, and no one person has access to all of them, which is why this book had to be a group effort where London’s story is told by food writers, architecture writers, journalists, activists, and even one MP. Books about London have a tendency to dwell on the Londons that have been and gone, but I am, as are all the writers in this book, interested in London as it is now, how we eat and live today; when history is invoked it is done so to find out where the city is going and how quickly, to track London’s velocity as it spreads outwards in radial pulses, seeing where kinetic energy has been transformed and stored as potential energy in a city where energy never truly dies, just changes form. Institutional food – hospitals, schools, prisons – has for the most part been avoided; these essays are about places where good food exists because of, not in spite of, the urban conditions that surround it. There are no purely historical pieces in this book and, apart from in the very first essay on The Port, there is no talk of ghosts (unless it is to exorcise them) or psychogeography (the word ‘liminal’ has been banned).

The chapters of this book are about the spaces and food that get us through the day-to-day, but unfortunately London is a city seemingly obsessed with masterpieces. It is intent on getting more grand, more beautiful, more expensive, more Michelin stars, more, more, more. London consumes the rest of the country, but it is also an autophagic city – self consuming. London: the city that ate itself was the headline to a perceptive 2015 Observer article by the paper’s architecture critic Rowan Moore – a city where ‘anything distinctive is converted into property value’, where working-class markets are shut, replaced with cookie-cutter street food placed on pseudo-public property; where food production is being shunted to its peripheries or out of the city altogether; where community centres are shutting and food banks are rising; where new restaurants open just to be a notch on a property developer’s bedpost. If Orwell’s vision of the future was a boot stamping on a human face forever, then I have an even more chilling one: a Five Guys opening in your neighbourhood, soon.

The title of this book, London Feeds Itself, is not intended to suggest that London is self-sufficient, or that it is a Singaporean city state (in fact, the idea that London is somehow innately different and disconnected from the country that surrounds it is the source of so much that is wrong with the city), but to celebrate an opposing vision of the capital to the vertigos of finance, property portfolios and masterpieces that are symptoms of its autophagy. It is also a simple statement of fact. London feeds itself, and it does so in its own unusual ways – in its warehouses, parks, church halls, mosques, community centres, and even its baths: spaces where monetary transaction is peripheral or even completely absent. In the media, London is praised, it is reviled, it is resented, and it is grudgingly admired, but it is very rarely talked about with love. I would like to change that – this is the version of London that I love, and it is the London that I, and all the writers of the book, would like to share with you too.

London plays itself

In Thom Andersen’s 2003 essay documentary, Los Angeles Plays Itself, the director interrogates the use of Los Angeles as a backdrop to films. Los Angeles, Andersen argues, is cinema’s hidden protagonist, its buildings, streets and monuments reconfigured, spat out and often disrespected into forms that resemble a version of the city unrecognisable to those who live there. Andersen reserves much of his ire for Hollywood location scouts, who lazily use the wealth of Modernist architecture scattered across the surrounding hills and valleys as the lairs of villains and gangsters, subverting the buildings’ utopian intentions and usage. Yes, Los Angeles might be a character in a film, but it is just that – a character. It is unwittingly playing a version of itself that does not exist.

I think of Andersen’s film when I read restaurant criticism in British broadsheet papers because London is usually the hidden protagonist of the review. Outside of the few hundred men (me included) who keep buying Iain Sinclair books and who walk round the North Circular for fun, restaurant criticism is the most-read urbanist writing in Britain today. Unlike almost every other branch of criticism – except, notably, architecture – restaurant writing is impossible to extract from place: whether it’s El Bulli or a caff on an industrial estate, the review starts with the journey there: where it is, who lives there, and how its location might be surprising (a small plates restaurant run by a white chef opening in Peckham in 2011) or typical (a small plates restaurant run by a white chef opening in Peckham in 2024). This makes restaurant criticism far more important than a list of things that went into someone’s mouth: it is writing that, by its very nature – in the decisions its authors make on where to write about, and how to write about it – is political.

In the months prior to the pandemic, when restaurants temporarily shut, I looked at the last hundred reviews from eight national broadsheets: 68% were for London restaurants, with 20% of those restaurants in Mayfair and Chelsea and another 20% in Soho and Fitzrovia. That’s 40% of the entire country’s restaurant reviews taken up by a few square miles of the most expensive real estate in central London, controlled by a handful of mega-landlords. Given that the readership of these papers lives largely outside of London, the reviews function much like Hollywood’s depictions of Los Angeles: a kind of light entertainment; a satire for those who have no intention of going. The object of the satire may vary: oligarchs, idiotic tourists, rich Arabs, east London hipsters, whatever nonsensical idea some chef has concocted to appeal to London foodies. But the upshot of this is that the London depicted in reviews – neophilic, absurd, infinitely affluent – bears little resemblance to the city as a whole.

When restaurant critics do eventually venture outside of the city centre, the effect is even more ruinous. The satire, having no obvious target to latch on to, moves to focus on the neighbourhoods themselves: south London is described as ‘stabby’, Elephant and Castle where you might ‘pick up a nasty skin condition’ – whole areas written off as shitholes while Britain’s food critics pretend they deserve the George Cross for getting on the Thameslink. These reviews have a genuinely pernicious effect: they become handmaidens of developer-led gentrification and displacement. Brixton and Peckham – two significantly Black neighbourhoods – have taken the brunt of this; here, restaurants and street food ventures are written up as new, exciting phenomena that did not exist there beforehand, with what was already flourishing there completely ignored. House prices go up and these restaurants – mainly white-owned, mainly with PR, mainly on property in the process of being developed – proliferate. The review...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 45 colour photographs |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Grundkochbücher | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | Claudia Roden • diasporic food • essay collection • food anthology • Food anthropology • Food culture • Gentrification • Jeremy Corbyn • jonathan nunn • London • london cuisine • london food scene • rebecca may johnson • Restaurant Guide • Ruby Tandoh • small fires • Street Food • Vittles |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80427-100-4 / 1804271004 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80427-100-1 / 9781804271001 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich