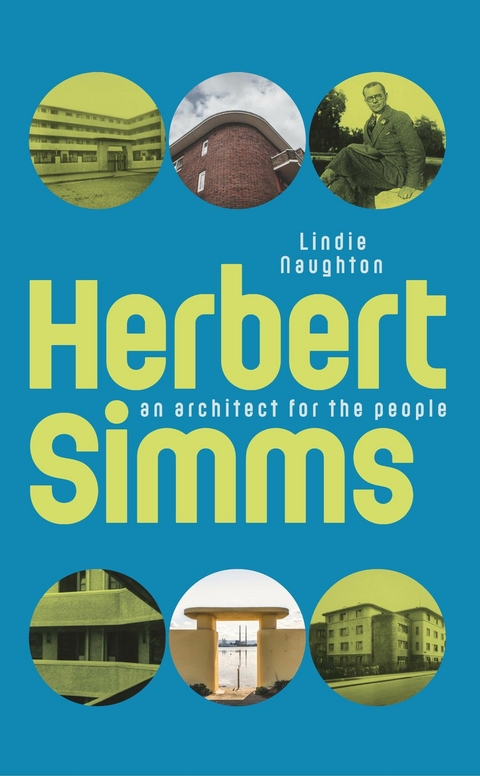

Herbert Simms (eBook)

280 Seiten

New Island Books (Verlag)

978-1-84840-912-5 (ISBN)

LINDIE NAUGHTON is a Dublin-based journalist and writer. Her books include Markievicz: A Most Outrageous Rebel; Lady Icarus: The Life of Irish Aviator Lady Mary Heath; Faster, Higher, Stronger: A History of Irelandxe2x80x99s Olympians; Letxe2x80x99s Run: A Handbook for Irish Runners, amongst others.

LINDIE NAUGHTON is a Dublin-based journalist and writer. Her books include Markievicz: A Most Outrageous Rebel; Lady Icarus: The Life of Irish Aviator Lady Mary Heath; Faster, Higher, Stronger: A History of Irelandxe2x80x99s Olympians; Letxe2x80x99s Run: A Handbook for Irish Runners, amongst others.

1

The Move into the Cities

From the early eighteenth century Dublin and other urban settlements all over the world were developing into cities, continuing a process sparked by the break-up of the feudal system many centuries earlier.

With living off the land no longer possible for most, and the industrial revolution seeing what we know as ‘work’ moving from handicrafts in the home to paid labour in the factory, thousands migrated from rural areas in search of paid work in the makeshift workshops and purpose-built factories of the cities. Housing these incomers, most of them impoverished, became a serious issue.

In 1798 James Whitelaw, vicar of St Catherine’s in the Liberties area of Dublin, had made a census of his ‘distressed’ parish, visiting every house, cabin and hovel. His graphic descriptions of city life were included in a two-volume history of the city of Dublin, published in 1818.

Inhabitants of the Liberties, ‘by far the greater part of whom are in the lowest stage of human wretchedness’, occupied narrow lanes:

where the insalubrity of the air usual in such places is increased to a pernicious degree by the effluvia of putrid offals, constantly accumulating front and rear. The houses are very high and the numerous apartments swarm with inhabitants. It is not infrequent for one family or an individual to rent a room and set a portion of it by the week, or night, to any accidental occupant, each person paying for that portion of the floor which his extended body occupies.

A single apartment ‘in one of those truly wretched habitations’ cost between one and two shillings a week. Two, three or even four families could share a single room: ‘hence at an early hour we may find from ten to sixteen persons of all ages and sexes in a room not 15 feet square, stretched on a wad of filthy straw, swarming with vermin, and without any covering, save the wretched rags that constitute their wearing apparel’.

Thirty to fifty people might be found living in a single dwelling: one house, No. 6 Braithwaite Street, contained 108 individuals. In the Plunkett Street of 1798, 32 houses contained 917 inhabitants – that’s an average of almost thirty souls per house.

Whitelaw queried why ‘slaughter-houses, soap-manufacturers, carrion-houses, distilleries, glass-houses, lime-kilns and dairies’ existed in the midst of these teeming slums. He highlighted the 190 licensed ‘dram-houses’ in the Thomas Street area where raw spirits were sold at all hours. Drunkenness was universal, even on the Sabbath, while the area supplied the more opulent parts of the city with its ‘nocturnal street walkers’.

A primitive approach to sanitation was a major cause of disease:

This crowded population … is almost universally accompanied by a very serious evil – a degree of filth and stench inconceivable, except by such as have visited those scenes of wretchedness … into the back yard of each apartment, frequently not ten feet deep, is flung from the windows of each apartment, the ordure and filth of its inhabitants; from which it is so seldom removed, that it may be seen nearly on a level with the windows of the first floor; and the moisture that after heavy rains, ouzes [sic] from this heap, having no sewer to carry it off, runs into the street.

The landlord was usually ‘some money-grasping wretch, who lived in affluence in, perhaps, a distant part of the city’. In one case the entire side of a four-storey house had collapsed. To the astonishment of Whitelaw, about thirty inhabitants continued to live in the ruined building and paid the landlord rent for the privilege.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Dublin’s population stood at a figure of 172,000 and it was considered the second city of the British empire. Its inner-city slums were the result not only of industrialisation and political changes but of an over-supply of expensive housing by speculative builders, followed by the arrival of rural labourers looking for work and needing accommodation. At the time Whitelaw and his co-authors were writing their history of the city, the Georgian streets and squares, both north and south of the Liffey, were still ‘spacious, airy and elegant’, although the number of civil servants looking for such accommodation had declined and the middle and professional classes were fleeing the filth and degradation of the city for the newly-created townships of Pembroke and Rathmines. Pembroke was mostly owned by the Earl of Pembroke, while Rathmines was controlled by middle-class businessmen such as Frederick Stokes, an English property developer.

Little changed over the next few decades despite major political upheavals. In 1801, largely in response to the 1798 rebellion by the United Irishmen, Ireland was integrated into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland under the Act of Union, with Irish MPs voting their parliament into extinction and Catholics promised the prize of emancipation under the union. The promise was not kept. Robert Emmet’s 1803 revolution was the final flicker of radical, urban-based rebellion: future rebellions would be led by a rural population protesting against iniquitous taxes and rents. Dublin’s decline from second city of the empire to provincial backwater had begun. For the next 122 years its 400-odd parliamentarians, many of them owners of large estates in rural Ireland, would conduct their business not in Dublin but at Westminster.

In the years following the Act of Union, the elegant mansions in Henrietta Street, Gardiner Street, Dominick Street, Summerhill and Mountjoy Square on the north side of the Liffey, many of them relatively new, were abandoned. Sites bought for building purposes were left derelict. Property prices crashed: a house valued at £2,000 before the union was worth about £55 in the 1820s. When not taken over by the better-off lawyers and bankers, the larger mansions fell into the hands of speculative investors, who sold yearly leases in the properties to smaller investors; these then let out rooms for a weekly rent. According to one visitor to the city in 1822, it was not possible to walk in any direction for half an hour in the city without coming upon ‘the loathsome habitations of the poor’.

Previously, the rich had lived in the main streets. Their employees, as well as the city’s small shop-keepers, publicans and businessmen, lived in the lesser streets behind or, in the case of Dublin, in ‘the Liberties’. As the name indicated, the Liberties was an area outside the city walls dating back to medieval times, which was not under the jurisdiction of the city. It later attracted wealthy merchants from the thriving weaving industries, as many of the street names indicate.

Following the departure of the wealthier and their middle-class entourages from the city centre, warrens of poorly-constructed buildings appeared down narrow alleys, lanes and stables originally designed to service the larger houses. From the 1840s onwards, housing of this nature was often demolished to make room for small factories and for the newly emerging railway lines and stations.

With no native source of cheap energy and no parliament in Dublin, Ireland’s few industries were left unprotected and forced to pay high duties on essentials such as coal. While its breweries and distilleries continued to employ large numbers of workers – as indeed did the manufacturers of biscuits and mineral waters – the silk industry was wiped out because of the unrestricted importing of raw and dyed silk into Great Britain and Ireland. Not even a reduction in wages could save it, although in 1824, when the first steamer service between Dublin and Liverpool was established, the silk industry was still employing an estimated 6,000 people in Dublin, about half what it had been at its peak. That would drop to no more than thirty to forty by 1832.

With its native industries in crisis, Ireland became primarily a supplier of cattle and agricultural goods to Britain. Dublin and its environs became a place of passage not only for livestock but increasingly for people; the great harbour of Kingstown, now Dún Laoghaire, built in the 1820s, symbolised the start of a new era in Irish trade.

Britain, the first truly industrialised nation in the world, had created an empire reaching all corners of the globe and was, by any measure, the most powerful nation in the world at the time. Lured by stories of well-paid work in the factories of Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, Birmingham and Glasgow, the rural poor arrived in Dublin seeking to find their way across the narrow Irish Sea to what seemed to them to be the Promised Land. Many got no further; others, who managed to scrape together the money for a ferry ticket, failed to find work and returned to Dublin soon after.

Before 1840 only 353 houses in Dublin were described as ‘tenements’; that is, a city house originally built for one family taken over by a landlord or ‘house jobber’. He then farmed them out as one-, two- and three-roomed ‘apartments’ for the highest rent possible without in any way improving the sanitation or adapting them for occupation by multiple families. Although scattered all over the city, most of the worst tenements were concentrated in the Gardiner Street and Dominick Street areas near the docks, while in the Liberties, the alleys and lanes off Francis Street, the Coombe and Cork Street were as crowded and filthy as ever. Of the 25,822 families living in tenements, a total of 20,108 lived in one room. As Whitelaw had found in 1798, one house could contain as many as ninety-eight people.

While not quite as bad as in Whitelaw’s time, sanitation remained rudimentary – usually consisting of an ash-pit and a ‘privy midden’, which consisted...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | Dirty Dublin • Dublin • Herbert Simms • Slums • Social Housing • tenements • The Emergency |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84840-912-5 / 1848409125 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84840-912-5 / 9781848409125 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich