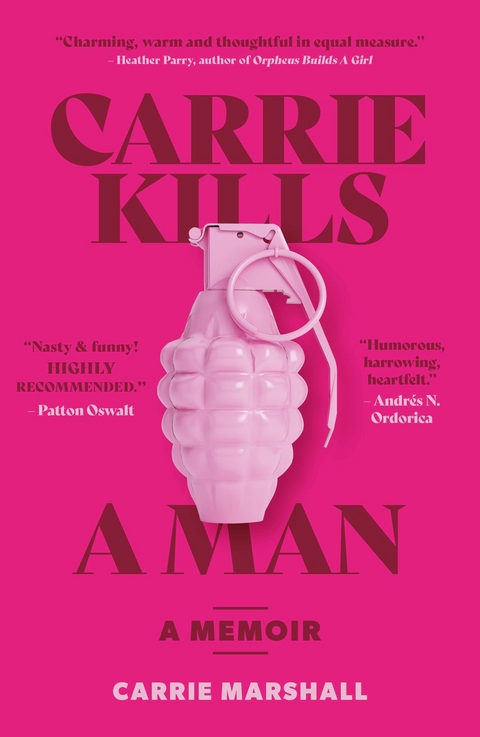

Carrie Kills A Man (eBook)

332 Seiten

404 Ink (Verlag)

978-1-912489-56-5 (ISBN)

Carrie is a writer, broadcaster and musician from Glasgow. She's the singer in Glaswegian rock band HAVR, a familiar voice on BBC Radio Scotland and has been a regular contributor to all kinds of magazines, newspapers and websites for more than two decades. She has written, ghost-written or co-written more than a dozen non-fiction books, a radio documentary series, and more.

Carrie is a writer, broadcaster and musician from Glasgow. She's the singer in Glaswegian rock band HAVR, a familiar voice on BBC Radio Scotland and has been a regular contributor to all kinds of magazines, newspapers and websites for more than two decades. She has written, ghost-written or co-written more than a dozen non-fiction books, a radio documentary series, and more.

Goody two shoes

I wasn’t born in the wrong body. I was born on the wrong planet.

Where other kids at my school obsessed over football, I was more interested in far-flung galaxies, space travel and sci-fi stories. I spent a lot of time daydreaming about them or staring in awe at the fantastic worlds and skyscraper-sized spaceships on the cover of sci-fi books. There was absolutely no doubt in my mind: I was going to be an astronaut.

Astronauts care little for earthly things, so instead of the on-trend Adidas satchels my classmates proudly wore I’d rock up to primary school with one of my dad’s old plastic briefcases full of model space rockets – a look that attracted the odd bit of negative attention and quite a lot of bemusement. I was regarded with some suspicion because I hated sport, talking about sport and being around people who talked about sport, and I couldn’t understand why I had to hang around with the boys instead of the girls, who seemed much more interested and interesting.

As if that wasn’t enough to make me stand out, I spoke with a different accent, I was new in town and I was younger than my classmates. That was because of my dad’s job: he worked for a construction company who moved us down the east coast of Scotland before cutting across to Ayrshire on the west. I’d started off in Inverness and moved down to West Lothian, where I was mocked for having an accent that was too posh; I changed it just in time to move to a different part of Scotland where my accent was now deemed too rough. One of the people who told me this was my next door neighbour, an older boy who wasn’t very nice to me but who grew up to be a very nice man. He’s my accountant now, but I have a long memory and I never pay his invoices on time.

I wasn’t bullied much, though. I’d have the odd parka-pulled-over-the-head encounter with some tiny fists trying to pummel my torso, but they were more like dancing than fighting. I didn’t experience anything particularly traumatic: I’d be called “poof” from time to time by people hoping to get a rise out of me, but even then I knew I was very bad at fighting so I didn’t rise to the bait. And I quickly found a protector in the form of Davy, a gruff, gentle giant of a boy who befriended me in much the same way you’d rescue a stray dog and who seemed to enjoy my company and my daft jokes. I didn’t quite cower behind his legs when I was threatened, but the other boys seemed to understand that if they messed with me, Davy would mess with them. Our friendship wasn’t based on that protection – it was more about debating which Madness song was best, swapping comic books and seeing who had the worst jokes; Davy was and is a funny guy – but I don’t doubt that if it weren’t for Davy I’d have had a much rougher time. If I were from another planet then Davy was the Elliott to my E.T., the friend who helped me navigate a world I didn’t understand.

I liked primary school. I came home with consistently glowing school reports, although my teachers despaired at my tendency to talk all the time. One of them, at her wits’ end after yet another barrage of questions, locked me in the stationery cupboard to stop me talking. My friends, I’m sure, have frequently felt like doing the same.

Primary school was also where I fell in love with books. I didn’t so much read books as inhale them, and according to my teachers, my reading age was double my actual one. Once I left primary school I began borrowing books not just with my own library card, but with my mum and dad’s cards too. I was drawn to horror – Stephen King’s Carrie, Christine and Salem’s Lot; James Herbert’s The Rats and The Fog; William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist – and SF, especially the bleak stuff such as Nevile Shute’s On The Beach and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I also adored wry, funny SF by the likes of Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Adams, both of whom had a huge influence on my sense of humour and on my writing style too. And I devoured endless crime novels ranging from the Scottish police procedurals of William McIvanney, and later, Ian Rankin, to the often repellent noir of James Ellroy and the macho mafiosi of Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. I’d take out ten books and finish them inside a week. To this day, I get really uneasy if I don’t have at least one unread book at home; I often accumulate vertiginous towers of to-read titles that I can topple in case of emergency.

Books were everything to me. An education – I often mispronounce words because I’ve never heard them spoken aloud; an adventure, taking me to the faraway galaxies I knew by now I wasn’t actually going to visit or showing me horrors that I hoped only existed in the authors’ imaginations; and more than anything, an escape. Books were a portal to other worlds, enabling me to escape not just from the outside world but from the cacophony inside my skull.

I can’t tell you exactly when I first tried on my mum’s heels or a skirt but it was definitely before I went to the big school, so it was several years before puberty. I remember a summer between primary school terms when I saw the family a few doors down playing in their front garden. The girls were a little older than me, and they’d persuaded, forced or bribed their little brother to dress in their clothes for their amusement. I recall seeing him and immediately going red from a mix of envy, embarrassment and confusion.

At home, I’d become fascinated by the women in the Littlewoods catalogue, the late-’70s equivalent of online shopping (and for older boys, the late ’70s equivalent of PornHub thanks to its pages of women in bras; the internet wouldn’t arrive for many more years). When nobody was around I’d stare at the girl-next-door models and the clothes they were modelling. I remember a very strong feeling of yearning, almost like when you have a huge crush on someone: there was a pull, a feeling that if I could just somehow enter the picture everything would be okay. I wanted to be as elegant and as beautiful as the women in the photographs. I wanted to be as beautiful as my mum, a tall, head-turning blonde who’d turned down the advances of footballer George Best at the height of his fame.

Had I been a cisgender girl, that wouldn’t have been a problem: we’ve all seen the trope of the young girl dressing up in her mum’s lipstick, pearls and heels a million times. It’s considered cute, because of course it is cute, and it can be a beautiful moment for mother and daughter. But it’s not considered cute or beautiful when boys want to do it.

I didn’t know much at that age, but I knew what the word sissy meant and that it was not something boys should be. But I couldn’t stop myself from wanting to see a very different me in the mirror, to feel more like the me I wanted to be. It felt right in a way I couldn’t articulate back then: the shiny polyester of an underskirt felt like a shiver against my legs, a sensation unlike anything I’d ever experienced from the clothes I’d worn as a boy, and as I layered up with a work skirt, American tan tights, M&S bra and pants and a plain but fitted blouse the different fabrics would move across each other in subtle, whispering ways. I’d try to keep my balance in too-big shoes, attempting to walk but only managing a stiff shuffle, but if I posed just right I could see my reflection in the mirrored wardrobe and see how the heels made my already long legs even longer. Dressed in everyday workwear I looked and felt like a business class Bambi: cute, unsteady and likely to fall on my arse any second.

Have you ever done the thing where you try something that’s above your pay grade – the really expensive facial scrub, the Egyptian cotton bedding with an incredibly high thread count, the birthday money bottle of wine or those huge fluffy bath sheets that you want to live inside and only ever come out of to scavenge for chocolate? That’s what female clothes felt like to me: satin sheets after sleeping beneath a scratchy, smelly old blanket.

It made me happy, if just for a short time. And it was always a short time, because I knew that if I got caught it would be the end of the world. I’d dress, totter around the room a bit while looking in the mirror and then carefully put everything back again. The happiness I felt faded fast and was replaced by much stronger, longer-lasting feelings I would become very used to: sadness, self-disgust and shame.

At night, I’d send secret prayers to God. I wanted him to kill me – painlessly in my sleep, because I’m a coward – and bring me back as a girl. He must have been on the other line because despite my best efforts for a very long time, he never did.

I hatched a plan. If God wasn’t willing to do it, I’d do it for him. So I decided I’d strangle myself. I’m very glad this was in the pre-internet era, because if it wasn’t I’d have googled the best way to kill myself properly – something I have done as an adult. But back then I was young, naive and completely unaware that you can’t strangle yourself with your own hands. I gave it a good go, but the best I could manage was to give myself a sore neck and have a bit of a cry.

I remember a school trip to see a pantomime - oh yes I do - and being utterly fascinated by the principal boy, a young woman playing a male character in tights and boots. But my only other memory of gender weirdness from that time is from when my family and I were in Belfast for our annual trip to see our...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.11.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Familie / Erziehung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Gender Studies | |

| Schlagworte | Humour • LGBTQ • Memoir • Trans |

| ISBN-10 | 1-912489-56-2 / 1912489562 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-912489-56-5 / 9781912489565 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 903 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich