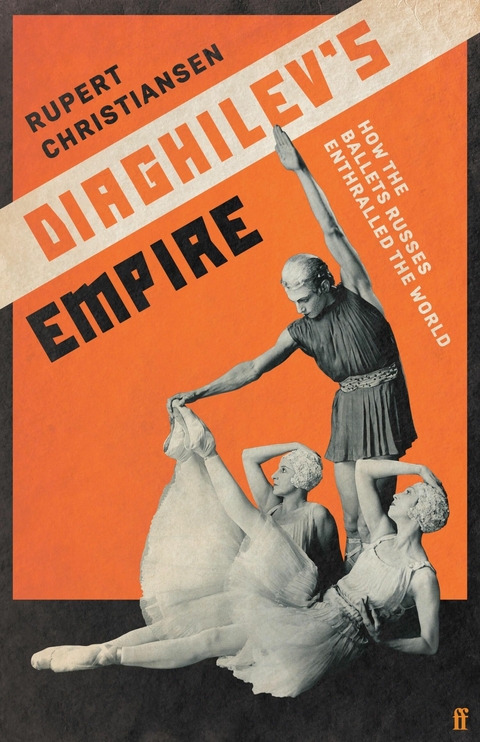

Diaghilev's Empire (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-34803-9 (ISBN)

Rupert Christiansen is The Spectator's dance critic. He was previously dance critic for The Mail on Sunday from 1995-2020, and has written on dance-focused subjects for many publications in the UK and USA, including Vogue, Vanity Fair,Harper's and Queen, The Observer,Daily Telegraph, The Literary Review, Dance Now and Dance Theatre Journal. He was opera critic and arts correspondent for the Daily Telegraph from 1996-2020, and is the author of a dozen non-fiction books, including the Pocket Guide to Opera and The Complete Book of Aunts (both published by Faber). He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1997 and lives in London.

Serge Diaghilev was the Russian impresario who is often said to have invented the modern art form of ballet. Commissioning such legendary names as Nijinsky, Fokine, Stravinsky, and Picasso, this intriguingly complex genius produced a series of radically original art works that had a revolutionary impact throughout the western world.Off stage and in its wake came scandal and sensation, as the great artists and mercurial performers involved variously collaborated, clashed, competed while falling in and out of love with each other on a wild carousel of sexual intrigue and temperamental mayhem. The Ballets Russes not only left a matchless artistic legacy - they changed style and glamour, they changed taste, and they changed social behaviour. The Ballets Russes came to an official end after many vicissitudes with Diaghilev's abrupt death in 1929. But the achievements of its heroic prime had established a paradigm that would continue to define the terms and set the standards for the next. Published to mark the hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Diaghilev's birth, Rupert Christiansen - leading critic and self-confessed 'incurable balletomane' - presents this freshly researched and challenging reassessment of a unique phenomenon, exploring passionate conflicts and outsize personalities in a story embracing triumph and disaster.

2

ROOTS

A quaint dusty fairy and her page, from the 1890

St Petersburg production of The Sleeping Beauty

In tribute to St Petersburg’s mighty river and Charles Dickens’s roistering eccentrics, they called themselves the Nevsky Pickwickians. A small fraternity of young men of the upper middle class – most of them old schoolfriends, half-heartedly studying law – they considered themselves a cut above their vulgar contemporaries, whose devotion to sports, drinking and womanising provoked them to scorn. Their own enthusiasms were more cerebral and dedicated to self-improvement of a romantic and aesthetic nature.

High-spirited and uproarious but passionately serious as only Russians can be, they met to debate the great issues of the day, the future of art, the mysteries of philosophy, advances in science. Politics they rather despised, but speech ran free, jovial minutes were kept and emotions rose fiercely in defence of truth. Whenever argument became too heated, it was the responsibility of bumbling Lev Rosenberg to ring a small bronze bell and call the meeting to order. This ritual was invariably ineffectual. ‘Shut up, you old Jew,’ the others would laughingly bellow,1 in an instance of the casual bantering racism commonplace in the 1890s, where this story begins in earnest.

‘Our tastes were still very far from being formed,’ one of their number later recalled. ‘We were enthusiastic about so many things: life was beautiful, so full of thrilling new discoveries that we could not afford the time to stop and criticise, even had we known how.’2 Yet there was much that they could experience only through the reports of foreign travellers, piano reductions of orchestral scores or articles in foreign journals. St Petersburg couldn’t be described as a backwater, but the new trends in London and Paris took time to arrive, and delay and distance gave Russian interest in them a peculiar perspective, a special glamour.

Four of this amiable outcrop of the Russian intelligentsia will play a significant part in the history of the Ballets Russes. Of these, Alexandre Benois, the natural president of the Nevsky Pickwickians, was the most sophisticated, cosmopolitan and erudite. As his name suggests, he was of French extraction – his grandfather a refugee from the 1789 Revolution, his father a well-respected architect. Their tales of the courtly culture of ancien régime Versailles fed Alexandre’s youthful imagination, leaving him with a penchant for rococo prettiness and gilded formality, offset by an equally intense fascination with the world of fairy tale and the supernatural. Throughout his long life – he died in 1960 – he would remain a romantic conservative, absorbed in the glories of the past and sceptical of shallow modern innovation. He seems to have been a very lovable man: warm-hearted and generous in temperament, devoted to his family and loyal to his friends, Benois was held in great affection and regarded as both an intellectual authority and as a moderating force on the more wayward personalities in the club.

Among these last was the diminutive and dapper Walter Nouvel, rarely seen without a cigar between his lips. Sharply intelligent and meticulously efficient, he was a musical connoisseur, altogether bullish in his views and on occasion hypercritical. Darkly handsome Dima Filosofov was less easy to read: the most overtly literary and intellectual of the group, neither expansive nor exuberant, and sometimes caustically satirical, he would later wander off into the fogs of Slavic mysticism. Benois’s friend Rosenberg was a late joiner. Bipolar, short-sighted and red-headed, secretly cursed with perverse sexual tastes, he was an upcoming art student, touched with genius as a colourist, who sought to disguise his Jewish origins by changing his name to Léon Bakst.

All of this oddly matched band were expert in the visual arts and worshipped the painting of the Old Masters. Yet they weren’t reactionaries: they also knew, by repute at least, about John Ruskin and William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement; they were versed in the ideas of Nietzsche and Ibsen’s realist dramas; they venerated the figure of Richard Wagner, and longed to visit the Bayreuth Festival – every cultured young man’s dream holiday destination.

But Benois and Nouvel also had another more rarefied yet lowbrow enthusiasm: ballet. To their peers anywhere else in Europe, this would have been inexplicable. Scarcely afforded any status as an art form in its own right, ballet was regarded as ineffably silly, its only purpose that of feeding the erotic fantasies of lascivious old gents aroused by the sight of shapely young female legs beneath short skirts. The dancing was merely formulaic; the plots were infantile pantomimes with exotic settings devoid of dramatic coherence or emotional depth. At best it provided light relief in lumbering grand operas – as in Meyerbeer’s epic Le Prophète, in which a jaunty skating divertissement was dropped incongruously and anachronistically into the third act of a drama focused on the Anabaptist revolt of 1530. In sum, ballet had neither intellectual content nor aesthetic dignity.

But it had not always been thus. Like opera, the art form to which it was most closely linked, theatrical ballet had developed out of a Renaissance court culture that had created highly formalised mimed theatrical entertainments, grounded in French and Italian models of elegant gesture and graceful deportment. Drawing on these sources, the Milanese choreographer Carlo Blasis developed a theory, history and vocabulary of movement that he moulded into a treatise entitled The Code of Terpsichore, published in several languages in 1830. Defining purity of bodily line according to the aesthetics of classical sculpture and specifying technical exercises, it would remain the basis of ballet’s pedagogy and philosophy throughout the nineteenth century.

In the 1830s and 1840s, ballet had enjoyed a period in the limelight, as a succession of trail-blazing female dancers took the opera houses of Europe by storm. In long skirts of layered white tulle (also known as tarlatan), they impersonated disembodied ghostly maidens who haunted their earthly lovers. Most sensationally, they jumped – and their capacity to leave the ground and appear airborne became fundamental to their myth. Acclaimed in Paris, Milan, London and St Petersburg was the Swedish-Italian Marie Taglioni, who flitted and hovered ethereally through La Sylphide on pointe – an accomplishment facilitated by blocking the toe of her satin slipper with cotton wads. This innovation was soon emulated by Carlotta Grisi and others in Giselle, another ballet with a spooky scenario co-written by Théophile Gautier, the prince of French belletrists and devotee of the dance. In contrast to these weightless other-worldly fairies, the likes of Fanny Elssler, Fanny Cerrito and Lucile Grahn presented more fiery and earthy stage personalities – Spanish señoritas, Venetian courtesans, bandit gypsies.

The young blades and dandies of the time were infatuated with them all, if fiercely partisan over their relative merits: in Paris, they were said to jostle for the privilege of drinking champagne from darling Taglioni’s satin slipper; some fool in Russia stewed and chewed another of these fetishised objects, covering it in a sauce Taglioni; while at Balliol College, Oxford, W. G. Ward, an undergraduate of Falstaffian proportions (and subsequently a prominent Catholic theologian) would amuse friends in his rooms by giving ludicrously camp imitations of Taglioni’s will-o’-the-wisp pirouettes and dainty bourrées.3

The fashion did not run deep and would not survive the mid-century – the next generation of stars shone less brightly, and the storylines came to seem preposterously insipid. ‘Ballet is dead and gone,’ mourned Charles Dickens in his magazine All the Year Round in 1864. That may have been a journalistic exaggeration but, by the 1880s, it was certainly looking desiccated, as poor wizened Madame Taglioni, once the toast of the town, was reduced to teaching daughters of the aristocracy how to curtsey. In London, the programming of a whole evening of ‘serious’ ballet was out of the question: aside from its peripheral role in opera, it featured chiefly as a course on the menu in the music-halls, providing an interlude of cavorting between the conjurors and the stand-ups.

Scandalous cases of wretched girls in the corps de ballet prostituting themselves to supplement their pitiful wages were a staple of the tabloid press and scarcely helped the profession’s reputation. In Paris, only the most strait-laced even raised an eyebrow at the idea of these vulnerable creatures being up for hire to smart young men with a laissez-passer to the notorious backstage foyer de la danse. The girls knew the deal, and nobody of any intelligence took an interest in the quality of their dancing, let alone in what they danced. A lucky few ended up ‘protected’ by members of the aristocracy. (Taglioni became the Comtesse de Voisins, though the marriage swiftly collapsed.)

From Milan eventually came something that woke everyone up, when, in 1881, the Teatro alla Scala staged the première of a blockbuster extravaganza – and it really was exactly that – called Excelsior. The conception of a flamboyant figure called Luigi Manzotti, who was blessed with a Busby...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.9.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Tanzen / Tanzsport | |

| Schlagworte | Ballet Russes • Nijinsky • pavlova • Picasso • Serge Diaghilev • Stravinsky |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-34803-3 / 0571348033 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-34803-9 / 9780571348039 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 15,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich