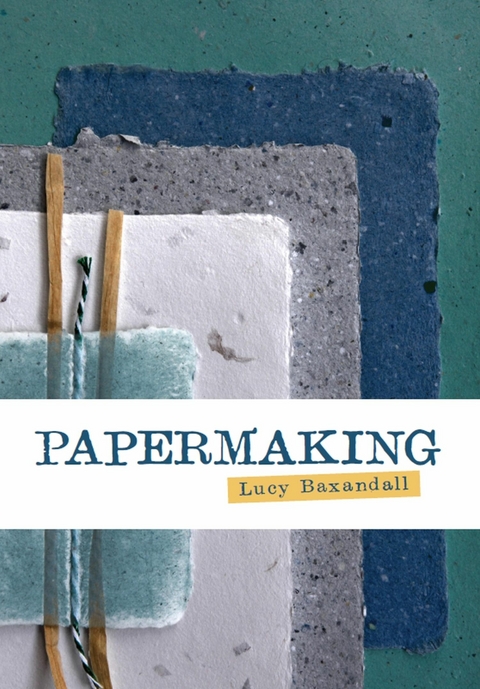

Papermaking (eBook)

96 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-1-78500-998-3 (ISBN)

Lucy Baxandall is a British hand papermaker and paper artist based in Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, where she runs a studio and a retail shop, Tidekettle Paper. She regularly teaches 2D and 3d papermaking and book arts workshops, and enjoys working with other artists who wish to use papermaking techniques in their projects.

CHAPTER TWO

GETTING STARTED

Now that you have everything you need to hand, it’s time to start making paper. As with cooking, it is a good idea to make sure all your ingredients and equipment as described in Chapter 1 are ready to go, so that you don’t have to go hunting for things when your hands are already wet and/or holding a fragile newly formed sheet. At the end of this chapter, you will find a troubleshooting section to help solve any problems you may encounter along the way.

At this point, I’m going to assume that you will be making paper straight after preparing your pulp. If you want to prepare pulp now to use later, just skip to the next section on pulp preparation and then return here to learn how to set up your workstation.

Setting Up Your Workstation

Choose a table or worktop to act as your papermaking surface. If you are concerned it might be damaged by water, protect it with a plastic sheet or waterproof tablecloth. One half of the space will hold your vat, the other your couching area. You can choose whether to work from left to right or vice versa. If you choose the vat-in-vat set-up, you should not need much other protection, but a towel placed under the outer vat will catch any stray drips.

The couching area will need more absorbent layers: a towel with old newspapers underneath will work fine and can be replaced as you go along if things get very soggy. Keep the edge of the towel tucked on top of the table to minimize dripping onto the floor.

On top of your newspapers and towel, place another towel, felt or blanket square. This will form the bottom layer of your fresh stack of paper and will be used to transport the wet sheets to the next stage of drying. You should have another towel/felt/blanket layer standing by to place on top of the finished stack.

The final layer consists of a kitchen cloth or thin fabric cloth on which your paper will rest. You will need several of these as you will interleave them between your fresh sheets. In most cases these can be reused for each stack, but if you plan on hanging your paper up to dry, you will need a larger supply as the cloths will be in use for the whole drying process. A bucket or tub of clean water should be placed on the table to wet your cloths ready for action and provide any other water you may need. A small container such as a yogurt pot is useful too, as we’ll see.

Now you are ready to prepare your pulp.

Preparing Your Pulp

- Dry fibre (new or recycled, or a mixture)

- Container of water for soaking

- Blender or paint mixer

- Jam jar

Whether you are using recycled paper or new semi-processed fibres, and whichever equipment you use to process it, the first few stages of preparation will be similar. Start out with around 100g of dry paper/fibre. While it’s not essential to weigh the fibre accurately when starting out, it’s a great habit to get into, as it becomes more important when you want to try more advanced techniques.

The humble kitchen blender is the friend of home papermakers. Get the most robust you can afford, but even a basic model will serve you well if treated kindly.

Firstly, cut or tear your recycled paper/board into pieces no larger than about 3cm square. If you are using thick board or a tough semi-processed fibre, you may find it easier if you peel it apart into thinner layers first. You could even jump ahead and soak it before tearing it up.

Once your fibre is in small pieces, it needs to be soaked to avoid damaging the blender or mixer later. You can use cold or warm water. At this stage you will notice a difference between recycled and new fibre. Unless your recycled paper is blotting paper or paper napkins/towels, it will take a while to absorb the water and darken. The new fibre will slurp the water up immediately and swell visibly.

By using recycled papers, you can avoid the extra stage of adding sizing, as some of the sizing added during manufacturing will stay in the pulp and should be sufficient to do the job.

When your fibre is thoroughly soaked (around twenty minutes for new fibre, an hour or so for recycled) you can start turning it into pulp.

Jam jar test: if you can see any significant chunks of unblended paper, give your pulp a few more seconds in the blender before checking again.

Place two handfuls of soaked fibre into your blender goblet and top it up with water to about two thirds full. Close the lid and blend on the lowest setting for about fifteen seconds, raising the setting if necessary until the fibre blends easily.

If the fibre does not move around freely, switch off and unplug the blender and remove some of the pulp. Add a little more water and try blending again. After about fifteen seconds, give the blender a rest and look at the pulp; it will probably need another few seconds. When the pulp looks smooth in the blender, pour a couple of tablespoonfuls into a jam jar or similar container with a lid. Add enough water so that when you shake it, you can hold it up and see the light through the liquid. If the fibres are evenly suspended with no obvious lumps, it is ready to make paper.

If there are still lumps, blend for a few more seconds and test in the jar again until you are happy. Pour the contents of the blender into your vat (which should be on your protected work surface with enough room to one side for your couching station) and repeat the blending process. Once you have two blender-loads in your vat, fill it about two thirds full of water. You may have to add part or all of another blenderload, but it is easier to add fibre than to remove it, so it’s best to err on the thin side to start with and add where needed.

If you are using a paint mixer instead of a blender, you will be able to process more fibre at once. Do the jam jar test in the same way. Fill your vat about a quarter full of fibre and top it up with water to two thirds full. This will allow you room to adjust the amounts if needed later on.

At this point, if you are using new fibre rather than recycled, it’s time to add your sizing. In a washing-up bowl vat, add about two tablespoons of proprietary sizing or starch paste (see ‘Home-made Sizing’ in Chapter 1) and mix well so that the sizing is not visible in the pulp and coats the fibres evenly.

Hollander Beaters

As you patiently blend single handfuls of fibre to make your paper, you may wonder how largerscale papermakers manage. Some historical paper mills in Europe and Asia still use waterpowered stampers, arrays of giant wooden hammers whose relentless pounding reduces plant fibres and rags to pulp. Most serious hand papermakers in the Western tradition like to use an electric-powered Hollander beater (though I know one whose beater has the option to be bicycle-powered). These come in various sizes, from so-called laboratory beaters, which are used to make small test batches in large mills, to monsters that you could comfortably take a bath in. My beater takes up to a kilo of fibre (dry weight) but with tougher fibres I would only beat about half of that in one sitting.

For those gripped by the papermaking bug, a Hollander beater is the holy grail. This machine grinds down and separates out fibres, rather than cutting them as a blender does. Running for hours at a time, it can create large quantities of pulp and reduce tough rags and plants to slurry. It can also create specialist pulps for translucent papers and pulp painting. This model was made by David Reina in the US.

The beater works in a different way from the blender, grinding the fibres down and separating them out with blunt blades on a wheel rather than cutting them, which makes for a stronger sheet. It can process cotton and linen rag, cut up and soaked just like other fibres, which would defeat even the strongest blender (trust me, I have tried). By beating certain fibres for several hours, the beater can alter their properties to make translucent paper or create a super-fine liquid pulp for painting. Though there are not many Hollander beaters in the UK (they are heavy and expensive), a few papermakers who have them will prepare pulp for you on request.

Pulling Your First Sheets

With your workstation set up and your pulp ready, it’s finally time to start making paper. After all the preparation, forming sheets is actually the fastest part of the whole process. Rinse your mould and deckle thoroughly under clean water before starting, or your first sheet will be uneven and may stick to the mesh. Make sure you have a clean couching cloth ready to receive the first sheet, and several waiting in your bucket of clean water. Wet the top towel or felt that sits just below the cloth so that it is well soaked but not dripping, and lay the damp cloth on top of this.

Hogging the vat: if left to their own devices, fibres will gradually sink to the bottom of the vat leaving a layer of clear water on top. Stir (hog) the vat before each sheet to ensure even distribution of fibres in the water.

Stand squarely in front of the vat and mix the pulp well with your hand until it is evenly suspended through the water. If left for any length of time, most fibres will settle to the bottom of the vat with a layer of clear water on top, and it’s a good idea to mix before each sheet.

Hold the mould and deckle as shown, with thumbs on top and fingers spread out to support the mould from underneath.

To hold your mould securely, your fingers...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.1.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Schlagworte | accessible • Artist • Collage • craft • Design • dye • EASY • embellish • environmentally friendly • Fibre • Garden plants • Handmade paper • Inspiration • lantern • layering • mould and deckle • NATURAL • papermaking • personalise • Pigment • Project • recycled • Reuse • Stationery • Sustainable • Textiles |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78500-998-2 / 1785009982 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78500-998-3 / 9781785009983 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 7,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich