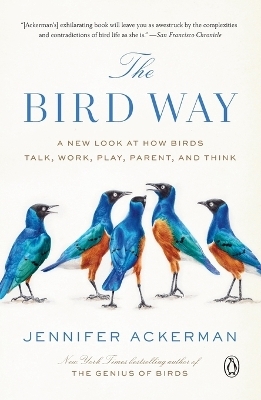

The Bird Way

Penguin USA (Verlag)

978-0-7352-2303-5 (ISBN)

“There is the mammal way and there is the bird way.” But the bird way is much more than a unique pattern of brain wiring, and lately, scientists have taken a new look at bird behaviors they have, for years, dismissed as anomalies or mysteries –– What they are finding is upending the traditional view of how birds conduct their lives, how they communicate, forage, court, breed, survive. They are also revealing the remarkable intelligence underlying these activities, abilities we once considered uniquely our own: deception, manipulation, cheating, kidnapping, infanticide, but also ingenious communication between species, cooperation, collaboration, altruism, culture, and play.

Some of these extraordinary behaviors are biological conundrums that seem to push the edges of, well, birdness: a mother bird that kills her own infant sons, and another that selflessly tends to the young of other birds as if they were her own; a bird that collaborates in an extraordinary way with one species—ours—but parasitizes another in gruesome fashion; birds that give gifts and birds that steal; birds that dance or drum, that paint their creations or paint themselves; birds that build walls of sound to keep out intruders and birds that summon playmates with a special call—and may hold the secret to our own penchant for playfulness and the evolution of laughter.

Drawing on personal observations, the latest science, and her bird-related travel around the world, from the tropical rainforests of eastern Australia and the remote woodlands of northern Japan, to the rolling hills of lower Austria and the islands of Alaska’s Kachemak Bay, Jennifer Ackerman shows there is clearly no single bird way of being. In every respect, in plumage, form, song, flight, lifestyle, niche, and behavior, birds vary. It is what we love about them. As E.O Wilson once said, when you have seen one bird, you have not seen them all.

Jennifer Ackerman has been writing about science and nature for three decades. She is the author of eight books, including The Genius of Birds, which has been translated into twenty languages and the forthcoming The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think. Her articles and essays have appeared in Scientific American, National Geographic, The New York Times, and many other publications, Ackerman is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship in Nonfiction, a Bunting Fellowship, and a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Introduction

When You've Seen One Bird

There is the mammal way and there is the bird way." This is one scientist's pithy distinction between mammal brains and bird brains: two ways to make a highly intelligent mind.

But the bird way is much more than a unique pattern of brain wiring. It's flight and egg and feathers and song. It's the demure plumage of a mountain thornbill and the extravagant tail feathers of an Indian paradise flycatcher, the solo song of a superb lyrebird and the perfectly timed duets of canebrake wrens, an osprey's hurtling dive toward the sea, and a long-legged heron's still, patient eyeing of the dark water.

There is clearly no single bird way of being but rather a staggering array of species with different looks and lifestyles. In every respect, in plumage, form, song, flight, niche, and behavior, birds vary. It's what we love about them. Diversity fascinates biologists. It fascinates birdwatchers, too, driving us to assemble life lists, to travel to far corners of the globe to visit a rare species or jump in the car to spot a vagrant blown in by a storm, to go "pishing" and whistling into the woods to draw that elusive warbler.

Watch birds for a while, and you see that different species do even the most mundane things in radically different ways. We give a nod to this variety in expressions we use to describe our own extreme behaviors. We are owls or larks, swans or ugly ducklings, hawks or doves, good eggs or bad eggs. We snipe and grouse and cajole, a word that comes from the French root meaning "chatter like a jay." We are dodos or chickens or popinjays or proud as peacocks. We are stool pigeons and sitting ducks. Culture vultures. Vulture capitalists. Lovebirds. An albatross around the neck. Off on a wild goose chase. Cuckoo. We are naked as a jaybird or in full feather. Fully fledged, empty nesters, no spring chicken. We are early birds, jailbirds, rare birds, odd birds.

As biologist E. O. Wilson once said, when you have seen one bird, you have not seen them all.

This is certainly true for behavior. Take white-winged choughs. Australians say it's easy to fall in love with these birds-and it is. They're adorable, charismatic, gregarious, comical: lined up on a narrow tree branch, six or seven red-eyed puffs of black feathers, tenderly preening one another in a pearl-like strand of endearment and affection. Clumsy fliers, they prefer to walk everywhere, swaggering through dry eucalypt woodlands with their heads strutting backward and forward like a chicken's. They pipe and whistle and wag their tails like puppies. They're fond of playing follow-the-leader or keep-away, rolling over one another to win possession of a stick or a slip of bark. About the size of a crow but slimmer-black with elegant white wing patches and an arched bill-they live in stable groups of four to twenty birds and are always, always found in clusters or huddles or lines. Like a tight-knit family, they do everything together, drink, roost, dust bathe, play, run in wide formation like a football team to share a food discovery. Together they build big bizarre nests of mud (or emu or cattle dung if they're in a pinch) set on a horizontal branch, queuing up on the limb, waiting their turn to add their bit of shredded bark, grass, or fur soaked with mud to the rim of the nest. Together they brood, guard, and feed the young. Members of family groups are rarely more than five or ten feet apart. I once saw three fledglings jammed together on the ground like the three wise monkeys, see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.

And yet there's a darker side to choughs, especially if the weather turns bad. They squabble and fight, one group pitted against another. Larger groups gang up on smaller groups, flying at them and pecking viciously, dislodging eggs from nests, and nests from trees. They are

| Erscheinungsdatum | 07.05.2021 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 16 B&W CHAPTER OPENER ILLUS. |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 141 x 213 mm |

| Gewicht | 306 g |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Naturführer |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| Schlagworte | Animal Books • animals • Binoculars • bird • bird book • bird book for kids • bird books • birder books • birder gifts • bird field guide • bird guide • bird identification books • bird puzzles for adults • Birds • bird watcher gifts • birdwatcher gifts • Birdwatching • Bird Watching • bird watching book • Genius of Birds • gifts for animal lovers • gifts for birders • life of birds • Nature • nature books • nature gifts • nature guides • New Zealand travel guide • rv gifts • Science • science books • science gifts • science gifts for adults • wildlife |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7352-2303-3 / 0735223033 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7352-2303-5 / 9780735223035 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

aus dem Bereich