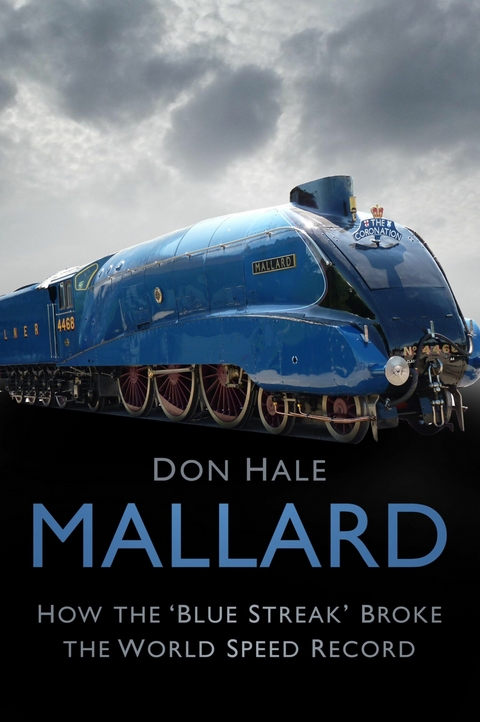

Mallard (eBook)

216 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-9291-6 (ISBN)

2

NIGEL GRESLEY AND THE GREAT NORTHERN

Around the time of the 1895 races to the north, Nigel Gresley, a young apprentice with the London & North Western Railway (LNWR), was employed at Crewe, Cheshire. While he must have watched the races with interest, he could not have known that some forty years later he would force the statisticians to rewrite their record books. For an observer of the 1890s, Gresley’s creations would have seemed beyond belief.

Born in Edinburgh on 19 June 1876, Gresley was the fourth son of the Reverend Nigel Gresley. He spent his early childhood years at the family home in Netherseale, near Swadlincote in Derbyshire, a comfortable existence with several live-in servants. Although Gresley came from a privileged background, he probably had the railway in his blood from birth: he was almost born on a train when his mother, Joanna, was forced to visit the Scottish capital whilst heavily pregnant. She had travelled to Edinburgh to see a specialist because she was suffering from problems in her pregnancy. It was a brave decision, for the experience would have been extremely slow, uncomfortable and arduous, requiring a journey via Burton-on-Trent to Derby, and then onward by a precarious schedule and numerous stops and starts to Scotland.

While she was in Scotland, Joanna Gresley gave birth in a lodging house at number 14 Dublin Street, a location probably influenced by the Reverend William Douglas, a close relative who lived at an adjacent property. The child was given the first name Herbert after one of his godfathers, and then Nigel, as a link to family ancestors dating back to Norman times. Perhaps pride in their heredity also partly explains the family’s unusually competitive spirit: family members were able to trace their roots back many generations to Robert de Toesni, who accompanied William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. After the Norman Conquest, the family took their name from the local village of Church Gresley, later making their home in nearby Drakelow in South Derbyshire. Gresley’s mother, Joanna Wilson, was a local resident hailing from Barton under Needwood.

The infant Gresley accompanied his mother home from Edinburgh by train. His father was the rector at St Peter’s church in the village, continuing a long-standing family tradition, and it was understood, if not expected, that young Gresley would follow in his father’s footsteps. But from an early age he told friends of his desire to become an engine driver, an unusual ambition for someone of his class in the days before a model railway became an essential possession for a small boy. Given his sheltered lifestyle, it certainly seems odd that he should want to get his hands dirty in some form of industrial occupation. But even as a child Gresley clearly possessed an individual streak that would serve him well in years to come. Perhaps he was influenced by newspaper reports about the great races or was simply fascinated by watching and listening to shunting operations on the nearby colliery branch line. He certainly seems to have been a railway enthusiast from an early age – and there are many cases where a child living next to a railway has gone on to work in them.

Gresley was sent away from Netherseale to attend preparatory school at Barham House, at St Leonard’s in Sussex, before completing his studies at Marlborough College. He enjoyed drawing and mechanical engineering and later won a science prize, distinguishing himself in both chemistry and German. His school reports also mentioned some success as a carpenter and noted that he was ‘very creative and good with his hands’. Little is known of his schooldays, but one imagines he had a typically Victorian education – the type designed to breed serious, solid, able empire-builders.

When Gresley left the college in July 1893 aged 17, he chose not to continue in formal education, finally confirming his unwillingness to enter the clergy. His family must have been disappointed, but they didn’t prevent him going for his chosen career. A young man of Gresley’s undoubted ability had many options, and he opted for a future in mechanical engineering on the railways – a job far removed from that of his father. In October that year, he gained employment as a premium apprentice at the Crewe works of the London & North Western Railway Company, under the watchful eye of Frank Webb, the chief mechanical engineer, and works manager Henry Earl.

St Peter’s Church. (Don Hale)

The Old Rectory at Netherseale. (Don Hale)

When Nigel Gresley first started work, he was paid the grand sum of 4 shillings per week but by the time he had completed his apprenticeship he was drawing a respectable wage of 24 shillings. The LNWR’s Crewe works was a fascinating place then, one of the biggest factories in the country, and one on which the Cheshire town depended. Renowned worldwide, it was as good a place as any for a young man to learn about railway engineering. However, despite the excellence of the factory, the works were frequently called upon to produce a series of bizarre and often poor locomotives. It was a good chance for an aspiring engineer to see what worked, and, just as importantly, what did not. Part of Gresley’s studies coincided with the miners’ strike of 1893–94, and he was able to gauge at first hand the reaction of many working-class railway workers as severe job losses, and then the restrictions of a four-day working week began to hit home.

Following his apprenticeship, Gresley spent time in the fitting and erecting shops at Crewe works, where he gained further practical experience. He then moved to the drawing office of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway at Horwich, Lancashire, where some very advanced locomotives were being designed. There he studied as a pupil again under John Aspinall, the chief mechanical engineer. At Horwich, Gresley worked in the test room and gained additional experience in the materials laboratory before moving to Blackpool as running-shed foreman. After less than a decade, this young man was starting to move up the career ladder.

In 1901, Gresley met and married Ethel Fullager, the daughter of a solicitor, from Lytham St Annes. She was two years older than her husband and an accomplished musician who had spent time in Germany studying the piano and violin. In the next few years two sons and two daughters were born to the couple, and Gresley became a devoted father, enjoying going on holiday with his children and taking them round the GNR locomotive yards to show them how the great engines were put together.

Through rapid promotion, Gresley then moved to become an outdoor assistant in the carriage and wagon department, transferring to Newton Heath, near Manchester. In 1902, he was made the works manager and then, after a reshuffle, was appointed assistant to the works superintendent. He was one of the youngest people in that kind of position on the railway, and already it was becoming clear that he was set for high office. Just over a year later, Gresley successfully applied for the position of superintendent with the carriage and wagon department on the Great Northern Railway. It was a big leap for him, in terms of both location and the opportunities it offered. He quickly made his mark, however, radically changing the shape of coaches from the fussy clerestory roof (which had a raised strip running down the middle to let light in) to a neater elliptical roof, which made the coaches seem much airier. Thanks to Gresley’s efforts at chassis design, the vehicles rode better, and he even found the time to upgrade the comfort of the interiors. The position carried a salary of £750 a year and seemed a good career move, but in March 1905, and still in his twenties, he moved again.

This time he went to a senior posting at Doncaster works, as subordinate to the well-known and highly respected chief mechanical engineer, Henry Ivatt. The move advanced still further Gresley’s rapid rise up the promotional ladder and provided him with an ideal base from which to learn, watch and wait. It was a highly prestigious position for someone so young: at precisely the right time, he had succeeded in putting his name into lights within a very large shop window. Even Gresley, though, cannot have known how much bigger that shop window would become in less than twenty years.

Of his personal life at this stage, rather less is known. Like many in his position at the time, Gresley seems to have been shy of publicity, leaving us with few indications of what he was really like. What we can say with certainty is that he was a keen sportsman who enjoyed tennis, golf, shooting and occasional rock climbing. He was also a mountain of a man, powerfully built, and with seemingly boundless enthusiasm. He towered above his friends and colleagues, who fondly called him ‘Tim’, a comical abbreviation of ‘Tiny Tim’. Several employees called him ‘Mr G’ or the ‘Great White Chief’, and later, following his knighthood, ‘Sir Nigel’.

This all suggests quite a likeable man, but Gresley was not popular with everyone. He was shrewd, ambitious and some claimed he was an opportunist – he was certainly a ‘master of diplomacy,’ and a man who knew exactly what he wanted and just how to get it. These skills would prove crucial in his rise to the top: pure ability is rarely enough to survive the guerrilla warfare and politics that accompany life in every big company. Henry Ivatt once claimed Gresley was ‘too pushy and too self-confident’. Others claimed he was ‘downright difficult’ to work with; the GNR board, however, welcomed his enthusiasm,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.9.2019 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Schienenfahrzeuge | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie | |

| Schlagworte | a4 pacific locomotive • blue livery • Bugatti • bugatti car • How the Blue Streak Broke the World Speed Record • mallard • mallard, a4 pacific locomotive, railway history, rail, speed record, steam locomotives, bugatti, sir nigel gresley, national railway museum, nrm • mallard, a4 pacific locomotive, railway history, rail, speed record, steam locomotives, bugatti, sir nigel gresley, national railway museum, nrm, bugatti car, blue livery, steam locomotive, steam engine, steam train, How the Blue Streak Broke the World Speed Record • national railway museum • NRM • Rail • railway history • sir nigel gresley • speed record • steam engine • steam locomotive • steam locomotives • Steam train |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-9291-3 / 0750992913 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-9291-6 / 9780750992916 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 20,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich