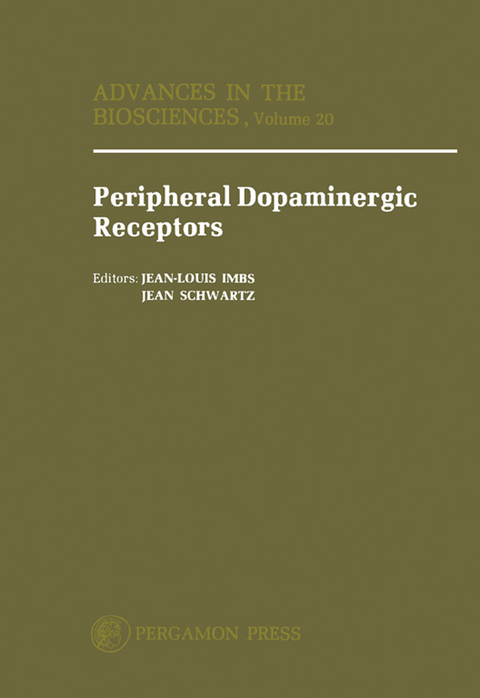

Peripheral Dopaminergic Receptors (eBook)

420 Seiten

Elsevier Science (Verlag)

978-1-4831-5616-3 (ISBN)

Peripheral Dopaminergic Receptors contains the proceedings of the Satellite Symposium of the 7th International Congress of Pharmacology held in Strasbourg, France, on July 24-25, 1978. The papers explore advances that have been made in understanding peripheral dopaminergic receptors and cover topics organized around five themes: dopamine measurement; structure-activity relationships; peripheral actions of dopamine; effects of dopamine on the kidney; and the physiological role of dopamine in the autonomic nervous system. This volume is comprised of 36 chapters and opens with a discussion on the dopamine vascular receptor, along with its agonists and antagonists. The reader is then introduced to the physiological and clinical implications of free and conjugated dopamine; dopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase in the renal artery of dogs; dopamine-induced relaxation of isolated dog arteries; and concentration and function of dopamine in normal and diseased blood vessels. The following chapters explore the possible involvement of endogenous substances in the cardiovascular actions of dopamine; the role of dopamine receptors as mediators of the neurogenic vasodilatation by dopaminergic agents; and implications of renal and adrenal dopamine for the role of conjugated dopamine. Studies on the peripheral cardiovascular activity of dopamine in the rat are also presented. This book will be of interest to practitioners in biosciences, pharmacology, physiology, and medicine.

Introductory Lecture The Dopamine Vascular Receptor: Agonists and Antagonists

Leon I. Goldberg, Committee on Clinical Pharmacology, Departments of Pharmacological and Physiological Sciences and Medicine, University of Chicago, 947 East 58th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60637, U.S.A.

ABSTRACT

This paper describes the research which led to the discovery of the renal vasodilating action of dopamine (DA) and the subsequent evidence indicating that the phenomenon was due to action on a specific vascular receptor. The structure activity relationship of agonists and lists of specific antagonists of this receptor will be presented and compared with agonists and antagonists reported to be active on other DA receptors. Physiological and clinical implications of these findings will be discussed.

Fifteen years has elapsed since my colleagues and I reported that dopamine (DA) dilated the renal vascular bed by an unusual mechanism (1–3). Since that time the peripheral actions of DA have become an extremely popular subject of research. Our initial findings have been confirmed (3) and other unusual actions of DA have been demonstrated (4). This meeting, the first to be concerned primarily with the peripheral actions of DA, represents an unusual opportunity for investigators from many countries to compare notes and discuss the many interesting problems which have arisen. The purpose of my paper is to set the stage for this meeting by reviewing what we have learned to date, and with this background, speculate about the future. My presentation will be concerned for the most part with personal experiences. Extensive reviews of literature have been presented elsewhere (1,4).

The fact that a meeting of this sort has been convened is most encouraging when I think back to the early days of DA research. When I first began studies of DA in 1959 at the National Heart Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, there was little evidence either in the brain or periphery that DA could serve any purpose except as a substrate for norepinephrine. Indeed, most studies indicated that DA was pharmacologically similar to norepinephrine with much less potency.

It is interesting to review the early history of cardiovascular studies of DA and, in particular, to note the results which suggested that DA may have unusual actions. The first reports of the synthesis of DA appeared in 1910 by Manich and Jacobsohn (5) and Barger and Ewins (6). In 1910 Barger and Dale (7) reported that DA exhibited a pressor potency in the spinal cat 1/50th that of d, 1-norepinephrine. In 1930 Tainter (8) reported that DA raised pressure in the spinal cat but that it was reversed by ergotoxine. In 1931 Hamet (9) reported that the pressor effect of DA in the anesthetized dog was reversed by yohimbine. These investigators, however, considered that these actions of DA were similar to those of epinephrine. The first clue that I could find of unusual actions of DA was in the studies of Gurd (10) reported in 1937. Gurd reported that the pressor effect of DA had a greater cardiac component than epinephrine. It was this difference that awakened my interest in DA more than 20 years later.

The most significant early studies demonstrating that DA was qualitatively different from other catecholamines was published in 1942 by Holtz and Credner (11). These investigators reported that DA differed from epinephrine in that DA decreased the blood pressure of the guinea pig and rabbit, whereas, epinephrine increased blood pressure in these species. Holtz and Credner postulated that the decrease in blood pressure was due to the formation of an aldehyde by action of monoamine oxidase. Subsequent investigations, however, demonstrated that inhibition of monoamine did not prevent the depressor effect. Later Holtz. and associates (12) suggested that the reduction in blood pressure was due to formation of a condensation product of DA, tetrahydropapaveroline. More recent studies, however, demonstrated that this material also was not responsible for the reduction in blood pressure.

In 1959 I began studying DA in the laboratories of Dr. Albert Sjoerdsma at the National Heart Institute. A major project of the laboratory was influence of monoamine oxidase inhibitors on metabolism of endogenous amines. I compared the effects of several endogenous amines in the anesthetized dog on contractility of the heart and blood pressure before and after administration of several monoamine oxidase inhibitors (13). DA was one of the amines studied. Figure 1 illustrates an experiment in which DA was compared to norepinephrine before and after administration of the monoamine oxidase inhibitor, R05-0700. As noted in the upper right panel, DA exerted a biphasic effect on blood pressure with a transient initial increase and then a more prolonged decrease in blood pressure. The effects of DA were potentiated by the monoamine oxidase inhibitor, whereas, the effects of norepinephrine were essentially unchanged. In 1960 Dr. David Horowitz, Dr. Sjoerdsma, and I (14) administered DA, apparently the first time to human beings, to determine whether similar potentiation would occur in patients treated for hypertension by monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Marked potentiation of the pressor effects of DA was observed in these patients.

Fig. 1 Norepinephrine and DA on arterial blood pressure (BP) and high contractile force (CF) in anesthetized dog. Note that the depressor effect of DA at a time when CF is increased (reprinted from reference 13 with permission of the publisher).

It was during the course of these studies that I began to consider the possibility that DA might be useful in the treatment of congestive heart failure. This concept was a direct result of my training as a graduate student with Professor Robert P. Walton at the Medical University of South Carolina. Professor Walton had postulated that if a sympathomimetic amine could be found which stimulates the heart without increasing heart rate or blood pressure, it would be useful in the treatment of heart failure. He carried out preliminary studies in this area but clinically useful drugs were not found (15). In subsequent investigations my colleagues and I investigated other sympathomimetic amines with similar lack of success (16).

In the initial investigations of DA at the National Heart Institute we found that DA could increase cardiac contractile force in animals (Fig. 2) (13) and pulse pressure in man (Fig. 3) (14) without significant effects on diastolic blood pressure or heart rate. On this basis Dr. Horowitz and I in collaboration with Dr. Samuel Fox conducted hemodynamic studies in normal subjects and in a few patients undergoing cardiac catheterization (17). We found that DA was able to increase cardiac output without significantly changing heart rate or diastolic arterial pressure when infused intravenously at a rate of 5-11 µg/kg/min.

Fig. 2 Effects of increasing intravenous doses of DA on cardiac contractile force, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate in anesthetized dogs. Data obtained from reference 20.

Fig. 3 Effects of intravenous infusions of DA and norepinephrine on directly recorded arterial pressure of a normal subject. Note the difference in diastolic and pulse pressure produced by DA and norepinephrine. Reprinted from reference 17 with permission of the publisher.

When I went to Emory University in 1961 my colleagues and I simultaneously began studies to delineate the mechanism of the depressor effects of DA in the dog and to determine the effects of DA in patients with congestive heart failure. In our first abstract read at the meetings of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology in 1962 (18), we reported that the depressor effects of DA were not blocked by beta-adrenergic blocking agents, atropine, or antihistamines. We also reported that phenoxybenzamine changed the pressor effect of a large dose of DA to depressor. Later that year at the Fall Pharmacology Meetings we described studies (19) with the perfused hindlimb of the dog. The full paper appeared in 1963 (20). When DA was injected directly into the perfusion circulation of the limb pressure increased (vasoconstriction). On the other hand, when DA was injected intravenously perfusion pressure decreased (vasodilation). Since section of the nerve trunks to the perfused limb greatly reduced or eliminated the vasodilation we concluded that the vasodilation was indirect and probably the result of a central nervous system or reflex mechanism. We concluded that the effect had to be mediated via the sympathetic nervous system since removal of the stellate ganglion prevented vasodilation of the limb. One problem during the study which disturbed us was that administration of the ganglionic blocking agent, hexamethonium, did not completely eliminate the depressor effect of DA, suggesting that another mechanism in addition to a neurogenic phenomenon was operating (Fig. 4). At that time, however, we had no indication that DA was a direct vasodilating drug. This early study should be viewed in the light of current knowledge of ganglionic (21) and pre-synaptic DA receptors (22). Later my colleagues and I came back to the problem in searching for the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.10.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Naturführer |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitsfachberufe | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Pharmakologie / Pharmakotherapie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| Technik | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4831-5616-8 / 1483156168 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4831-5616-3 / 9781483156163 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich