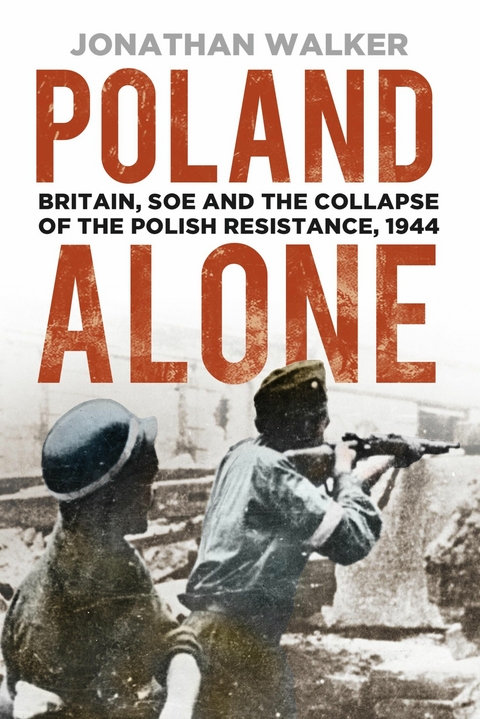

Poland Alone (eBook)

192 Seiten

Spellmount (Verlag)

978-0-7524-6943-0 (ISBN)

JONATHAN WALKER is a member of the British Commission for Military History and a former Honorary Research Associate at the University of Birmingham. He is the author of five books for Spellmount: The Blood Tub: General Gough and the Battle of Bullecourt; War Letters to a Wife (as editor); Aden Insurgency: The Savage War in South Arabia; Poland Alone: Britain, SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance, 1944 (which has been translated into Polish to great acclaim); and The Blue Beast: Power and Passion in the Great War. In addition to contributing to other recent military history publications, he has appeared on BBC radio and television programmes. He lives in Devon.

Chapter Two

The Polish Home Army

Despite the surrender of the Polish Armed Forces in early October 1939, Poland itself had never surrendered. Even as Hans Frank was installing himself in Wawel Castle, Kraków, the Underground State (Państwo Podziemne) was starting to function. Because much of Poland’s history had been one of occupation or oppression, guerrilla warfare and clandestine operations were familiar to the Poles and early resistance organisations, such as Polska Organizacia Wojskowa were revered. However, these ideas of resistance were not the preserve of a minority as in most other occupied European countries, but were ingrained in all Poles. Nevertheless it was always expected that guerrilla tactics would be employed initially against the Soviet Union rather than Germany, and there remained the difficult question of how to weld together the disparate political and military resistance movements.

The Polish Government-in-exile, under the firm leadership of General Sikorski, pulled together the main political parties including the Peasant, National Democratic and the Polish Socialist Party to form the nucleus of a civil underground state. Only the extreme right-wing Nationalist Party and the communist Polish Workers Party, who were eventually to set up a competing government and army, refused to join the coalition. However, those political leaders who chose to remain in Poland and go underground were constantly in fear of their lives. Early losses included the leading members, Mieczysław Niedziałkowski and Maciej Rataj, who after arrest and interrogation at Gestapo HQ in Warsaw, were taken to a killing ground in the Kampinos Forest, just west of Warsaw and executed in June 1940.1

For reasons of security and to improve liaison with the Allies, as well as to co-ordinate Polish military units worldwide, the Polish Government-in-exile remained in London. From there, it directed the administration and policies of both an underground civilian administration and military resistance movement in occupied Poland. This clandestine civilian Underground State, or ‘Home Government’ (Delegatura Rządu) comprised numerous departments to look after the needs of a suppressed population. The preservation of a Polish press, culture, education and welfare system were of paramount importance and even ‘shadow’ departments of Trade, Industry, Communications and Agriculture were established in the hope that they would, one day, form part of an independent Polish government.

During the years of occupation, the Germans stripped Poland of its industry and financial means of support. They also destroyed the Polish educational system by closing all schools except technical colleges, capable of producing tradesmen for the Reich. Professors, teachers and lecturers were expelled from their gymnasia (lower secondary schools) and higher education, or even eliminated. Yet the Underground State still managed to organise the secret education of Polish children in safe houses, by teachers who had survived the round-ups. And the shutdown also provided an unexpected boost for the resistance; for at a stroke, large numbers of science and research academics were sent home and could turn their minds wholeheartedly to devising plans to undermine German control.2

The main practical way to oppose the enemy was by military resistance. The main military underground organisation within Poland was initially the Service for the Victory of Poland (SZP), which operated from September to December 1939. Then on the orders of General Sikorski, the SZP was integrated into a new formation known as the Union for Armed Struggle or ZWZ (Zwiazek Walki Zbrojnej). The first military commander of ZWZ was briefly Major-General Michał Tokarzewski-Karaszewicz (‘Torwid’), who left to command the military resistance in the Soviet controlled Polish sector and was replaced by General Stefan Rowecki (‘Grot’).3 The ZWZ operated as an important intelligence gathering, sabotage and propaganda organisation until its re-birth on 14 February 1942 as the Armia Krajowa (Home Army or ‘AK’). Again, the extreme nationalist militia (NSZ) and communist Polish People’s Army (Armia Ludowa) were excluded, but the strength of the new organisation was that all levels of the resistance were now subordinate to the Commander-in-Chief, General Grot-Rowecki and the Home Army High Command; ultimate control was still exercised by the Government-in-exile in London. The AK had become the largest and most powerful resistance organisation in occupied Europe, with a formidable structure and a High Command split into seven separate areas of responsibility, known as bureaux (or in Polish, Oddziały Sztabu Generalnego WP). These bureaux covered operations, personnel, welfare, supply, command and communications and most famously, ‘Intelligence and Counter-intelligence’ (Bureau II) and ‘Information and Propaganda’ (Bureau VI).4

The organisation of AK resistance had to be based in the central General Government sector, where it enjoyed widespread support, for the western part of Poland, incorporated into the Reich, was largely untouchable. There, Germans had been introduced into the local population and together with Volksdeutsche, they provided the German security forces with a formidable eavesdropping source, making clandestine operations extremely difficult. Although the AK was an underground army, it was organised and officered in very much the same way as a conventional army. In place of regiments based on county affiliations, units were assembled according to ‘provinces’, which were further broken down into districts, regions and areas, each with their own commander. These chiefs had the traditional military accompaniment of adjutants, staffs, quartermasters and liaison officers, together with attached specialist intelligence and signals units. However, although there were higher commands, such as divisions, these lacked transport and normal divisional arms such as artillery, and numbered far fewer men than a conventional British Army division; in the case of the 27th Vohlynian Infantry Division, the unit listed 7,300 soldiers, including 500 women and a divisional staff of 126. The basic and widespread operational unit remained the platoon and it was estimated there were over 6,500 platoons in the General Government sector, each consisting of approximately fifty men. But for all the courage and dash that these units possessed, by 1944 the estimated 350,000-strong army was still handicapped by a chronic lack of arms, with perhaps only 12% of the soldiers possessing a weapon.5

Home Army detachments were made up of all social classes, ranging from the poor peasant and forest dweller through to professionals, such as doctors and lawyers. There were AK men who spent their entire war years in the service of the Home Army, while there were others who worked in civilian jobs by day and took part in clandestine operations at night. Then there were those who were on the run from the Gestapo or escapees from prisons and penal camps, who joined armed bands in the forests across Poland. Consequently, some never donned a uniform and if they did, it could range from pre-war Polish kit to British Army ‘battle-dress’, which had been dropped in containers by parachute. Use was even made of German army uniforms, though captured Wehrmacht smocks would always bear the red and white armband. Similarly, German helmets would be adorned with a white eagle or the red and white band, together with the underground unit’s insignia.

RAF supply drops containing charges and explosives were eagerly awaited by AK units but most had to make do with local materials. The explosive compound, Cheddite, was a favourite but procuring its main element, potassium chlorate, took ingenuity – stocks had to be stolen from factories or rolling stock. Other stolen chemicals were put to good use when the resistance broke into rail yards, and added the chemicals to the grease on the wheels of railway engines, making the brakes sieze. They would also apply time-fused bombs to petrol wagons awaiting dispatch. But more often than not, trains would have to be attacked in open country with varying degrees of success. If a single explosive was placed on the track, which blew up as the train passed over it, only limited delays of perhaps four hours, would result. However, on occasions the AK were able to lay charges at intervals along the track so that when recovery trains came to retrieve a damaged engine, further explosions occurred which wrecked these trains further down the line; chaos ensued and lines could be out of action for several weeks.

In April 1944, The Polish Government-in-exile in London ordered the AK to carry out numerous rail sabotage missions as part of ‘Operation Jula’. Such concerted action was designed to show the Soviets that the AK were capable of mounting operations that could materially assist the Red Army advance. One member, ‘Szyb’ was only too keen to take part:

We set out at dusk, taking ladders with us to fix the charges properly under the low railway bridge. We went with a numerous escort. We from Warsaw had four bren-guns as our personal weapons…we squatted under the bridge, though not without having to scramble away when a five-man patrol walked over the bridge. The charges had been placed during an interval between trains. At a given moment, we saw a bright flash in the direction of the River Wisła; some seconds later we heard a powerful explosion, followed by the staccato of rifle and automatic fire. Tadzunio and Felix had done their bit.

And then our turn came. Two trains were coming, one in each direction. They were going to pass...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.8.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Britain SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance 1944 • Britain SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance 1944, holocaust, nazi, hitler, concentration camp, special operations executive, polish underground, home army, RAF, royal air force, soviet control, resistance movement, second world war, world war two, world war 2, world war ii, wwii, ww2 • Concentration Camp • Hitler • Holocaust • home army • Nazi • polish underground • RAF • resistance movement • Royal Air Force • Second World War • soviet control • Special Operations Executive • World War 2 • World War II • world-war-ii, second-world-war, holocaust, nazi, hitler, concentration camp • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-6943-6 / 0752469436 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-6943-0 / 9780752469430 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich