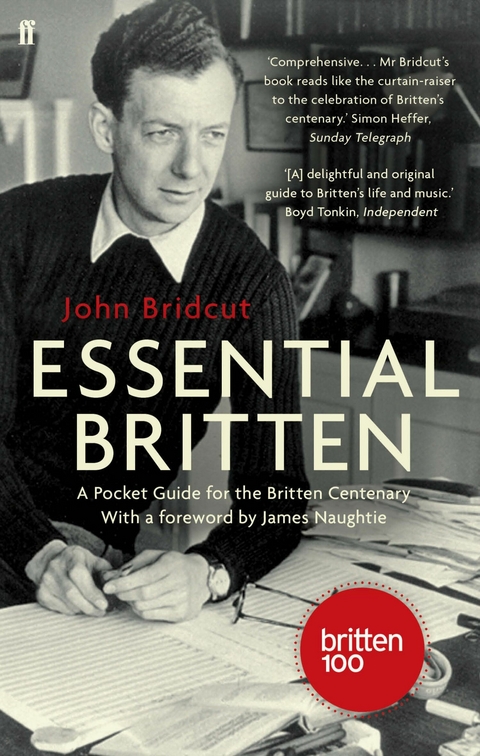

Essential Britten (eBook)

448 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-29074-1 (ISBN)

John Bridcut is a documentary film-maker for British television. His enthusiasm for English music has been lifelong, and his feature-length films, Britten's Children (2004), The Passions of Vaughan Williams (2008) and Elgar: The Man Behind the Mask (2010), have won awards. His most recent composer-portraits have been The Prince and the Composer (2011), in which HRH The Prince of Wales explored the life and music of Hubert Parry, and Delius: Composer; Lover, Enigma (2012). Other film subjects have included Prince Charles, Rudolf Nureyev, Roald Dahl, Hillary Clinton, Mstislav Rostropovich and the Queen. His book Britten's Children was published in 2006.

John Bridcut, author of the acclaimed 'Britten's Children', has included significant fresh material which will make the book indispensable for Britten aficionados as well as for those who are discovering the composer's music for the first time. This guide is all about finding a way into Britten's music. An outline of planned chapters:- The Top Ten Britten pieces- Critics' First Impressions- Britten's Life- Britten and Pears- The things they said- The Music (stage works, choral works, songs, chamber music, orchestral works)- The Interpreters of Britten's work- Britten as Performer- The Impresario (English Opera Group and Aldeburgh Festival)- Britten's Homes- Trivial Pursuits

John Bridcut is a documentary director for British television. He has had a lifelong enthusiasm for English music , and his feature-length films Britten's Children (2004) and The Passions of Vaughan Williams (2008) have won awards. He is currently working on a portrait of Elgar. In 2008, he produced a BBC documentary Charles at 60: The Passionate Prince for the BBC. Other film subjects have included Rudolf Nureyev, Roald Dahl, Hillary Clinton, and the Queen. His two books, Britten's Children and The Faber Pocket Guide to Britten, were published in 2006 and 2010 respectively.

Benjamin Britten defined the role of the composer in the eloquent acceptance speech he gave after receiving the Robert O. Anderson Aspen Award in Colorado in August 1964. The creator of the War Requiem two years earlier was chosen ahead of 100 artists, scholars, writers, poets, philosophers and statesmen as ‘the individual anywhere in the world judged to have made the greatest contribution to the advancement of the humanities’. I remember exploring this speech a few years later in a General Studies class at school, and being struck by how unusual and stimulating it was. Britten’s prize amounted to more than £140,000 (tax-free) in today’s money.

I Ladies and Gentlemen, when last May your Chairman and your President told me they wished to travel the 5,000 miles from Aspen to Aldeburgh to have a talk with me, they hinted that it had something to do with an Aspen Award for Services to the Humanities – an award of very considerable importance and size. I imagined that they felt I might advise them on a suitable recipient, and I began to consider what I should say. Who would be suitable for such an honour? What kind of person? Doctor? Priest? A social worker? A politician? Well, … ! An Artist? Yes, possibly (that, I imagined, could be the reason that Mr Anderson and Professor Eurich thought I might be the person to help them). So I ran through the names of the great figures working in the Arts among us today. It was a fascinating problem; rather like one’s school-time game of ideal cricket elevens, or slightly more recently, ideal casts for operas – but I certainly won’t tell which of our great poets, painters, or composers came to the top of my list.

Mr Anderson and Professor Eurich paid their visit to my home in Aldeburgh. It was a charming and courteous visit, but it was also a knock-out. It had not occurred to me, frankly, that it was I who was to be the recipient of this magnificent award, and I was stunned. I am afraid my friends must have felt I was a tongue-tied host. But I simply could not imagine why I had been chosen for this very great honour. I read again the simple and moving citation. The key-word seemed to be ‘humanities’. I went to the dictionary to look up its meaning; I found Humanity: ‘the quality of being human’ (well, that applied to me all right). But I found that the plural had a special meaning: ‘Learning or literature concerned with human culture, as grammar, rhetoric, poetry and especially the ancient Latin and Greek Classics’. (Here I really had no claims since I cannot properly spell even in my own language, and when I set Latin I have terrible trouble over the quantities – besides you can all hear how far removed I am from rhetoric.) Humanitarian was an entry close beside these, and I supposed I might have some claim here, but I was daunted by the definition: ‘One who goes to excess in his human principles (in l855 often contemptuous or hostile)’. I read on, quickly. Humanist: ‘One versed in Humanities’, and I was back where I started. But perhaps after all the clue was in the word ‘human’, and I began to feel that I might have a small claim.

II I certainly write music for human beings – directly and deliberately. I consider their voices, the range, the power, the subtlety and the colour potentialities of them. I consider the instruments they play – their most expressive and suitable individual sonorities, and where I may be said to have invented an instrument (such as the Slung Mugs of Noye’s Fludde) I have borne in mind the pleasure the young performers will have in playing it. I also take note of the human circumstances of music, of its environment and conventions; for instance, I try to write dramatically effective music for the theatre – I certainly don’t think opera is better for not being effective on the stage (some people think that effectiveness must be superficial). And then the best music to listen to in a great Gothic church is the polyphony which was written for it, and was calculated for its resonance: this was my approach in the War Requiem – I calculated it for a big, reverberant acoustic and that is where it sounds best. I believe, you see, in occasional music, although I admit there are some occasions which can intimidate one – I do not envy Purcell writing his Ode to Celebrate King James’s Return to London from Newmarket. On the other hand almost every piece I have ever written has been composed with a certain occasion in mind, and usually for definite performers, and certainly always human ones.

III You may ask perhaps: how far can a composer go in thus considering the demands of people, of humanity? At many times in history the artist has made a conscious effort to speak with the voice of the people. Beethoven certainly tried, in works as different as the Battle of Vittoria and the Ninth Symphony, to utter the sentiments of a whole community. From the beginning of Christianity there have been musicians who have wanted and tried to be the servants of the Church, and to express the devotion and convictions of Christians, as such. Recently, we have had the example of Shostakovich, who set out in his ‘Leningrad’ Symphony to present a monument to his fellow citizens, an explicit expression for them of their own endurance and heroism. At a very different level, one finds composers such as Johann Strauss and George Gershwin aiming at providing people – the people – with the best dance music and songs which they were capable of making. And I can find nothing wrong with the objectives – declared or implicit – of these men; nothing wrong with offering to my fellow-men music which may inspire them or comfort them, which may touch them or entertain them, even educate them – directly and with intention. On the contrary, it is the composer’s duty, as a member of society, to speak to or for his fellow human beings.

When I am asked to compose a work for an occasion, great or small, I want to know in some detail the conditions of the place where it will be performed, the size and acoustics, what instruments or singers will be available and suitable, the kind of people who will hear it, and what language they will understand – and even sometimes the age of the listeners and performers. For it is futile to offer children music by which they are bored, or which makes them feel inadequate or frustrated, which may set them against music for ever; and it is insulting to address anyone in a language which they do not understand. The text of my War Requiem was perfectly in place in Coventry Cathedral – the Owen poems in the vernacular, and the words of the Requiem Mass familiar to everyone – but it would have been pointless in Cairo or Peking.

During the act of composition one is continually referring back to the conditions of performance – as I have said, the acoustics and the forces available, the techniques of the instruments and the voices – such questions occupy one’s attention continuously, and certainly affect the stuff of the music, and in my experience are not only a restriction, but a challenge, an inspiration. Music does not exist in a vacuum, it does not exist until it is performed, and performance imposes conditions. It is the easiest thing in the world to write a piece virtually or totally impossible to perform – but oddly enough that is not what I prefer to do; I prefer to study the conditions of performance and shape my music to them.

IV Where does one stop, then, in answering people’s demands? It seems that there is no clearly defined Halt sign on this road. The only brake which one can apply is that of one’s own private and personal conscience; when that speaks clearly, one must halt; and it can speak for musical or non-musical reasons. In the last six months I have been several times asked to write a work as a memorial to the late President Kennedy. On each occasion I have refused – not because in any way I was out of sympathy with such an idea; on the contrary, I was horrified and deeply moved by the tragic death of a very remarkable man. But for me I do not feel the time is ripe; I cannot yet stand back and see it clear. I should have to wait very much longer to do anything like justice to this great theme. But had I in fact agreed to undertake a limited commission, my artistic conscience would certainly have told me in what direction I could go, and when I should have to stop.

There are many dangers which hedge round the unfortunate composer: pressure groups which demand true proletarian music, snobs who demand the latest avant-garde tricks; critics who are already trying to document today for tomorrow, to be the first to find the correct pigeon-hole definition. These people are dangerous – not because they are necessarily of any importance in themselves, but because they may make the composer, above all the young composer, self-conscious, and instead of writing his own music, music which springs naturally from his gift and personality, he may be frightened into writing pretentious nonsense or deliberate obscurity. He may find himself writing more and more for machines, in conditions dictated by machines, and not by humanity: or of course he may end by creating grandiose clap-trap when his real talent is for dance tunes or children’s piano pieces. Finding one’s place in society as a composer is not a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.10.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Klassik / Oper / Musical |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Singen / Musizieren | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-29074-4 / 0571290744 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-29074-1 / 9780571290741 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich