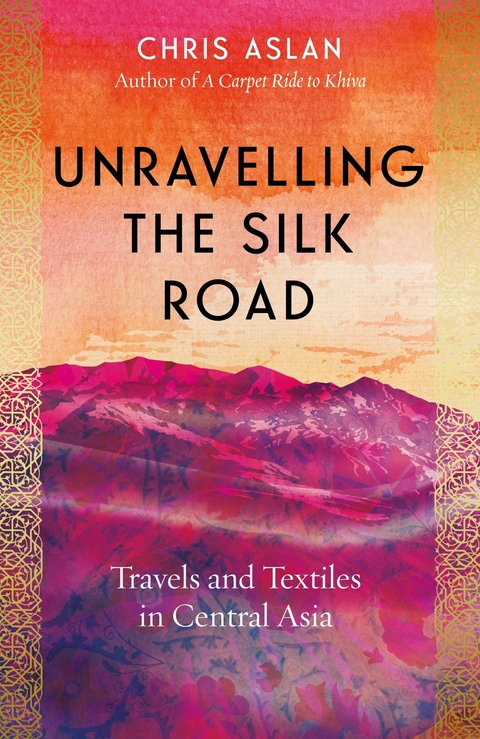

Unravelling the Silk Road (eBook)

352 Seiten

Icon Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78578-987-8 (ISBN)

Chris Aslan

Chris Aslan

INTRODUCTION

Spinning a Yarn

If I unpick my own road to Central Asia, it begins in the school library as I studied Soviet politics. In 1990, every world map was dominated by a huge red smear that crossed all the way from Europe to the Pacific. This was the Soviet Union. Lazily, I had assumed that it was just the communist name for Russia, and often people used the terms Soviet or Russian interchangeably. However, halfway through my course, the Soviet Union collapsed, and I decided to write my dissertation on the role of nationalism in its break-up. Reading more, I began to discover just how varied the peoples of the Soviet Union were, in terms of religion, language and ethnicity, and that a more accurate description of it was the Soviet Empire.

The Kazakh Socialist Republic alone was roughly the size of Western Europe. These were significantly large areas of non-Russian Soviet presence. I discovered Abkhazians, Georgians, Turkmen, Chechens, Tartars and Kalmyks, and found illustrations of these people in their national dress.

I was gripped. Although my parents are English, I was born in Turkey and spent my childhood there as my father was a professor at a university in Ankara. I knew that the Turks had originally come east from Central Asia, but hadn’t realised that there were so many other Turkic peoples out there, all sharing linguistic similarities.

Ruling over the largest contiguous empire the world has ever known was a centralised government that made economic decisions which I couldn’t understand. I read how in the twilight years of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika allowed greater economic freedom, combined with subsidised public transport and a burgeoning unofficial market. This meant that a Georgian villager could pick two buckets of apricots from the trees in her orchard, get on a bus to the airport, fly over three hours to Moscow, sell the apricots on the street and then fly back to Georgia again that evening. And still make a tidy profit.

Now, though, these new countries, still vastly overshadowed by Russia, were having to make their own way in the world.

My interest in the region continued. I was determined to travel along the Silk Road and see some of these exotic former Soviet countries for myself. I managed to get a travel bursary from Leicester University, on the proviso that it funded something related to my course. I was studying media and journalism, so I contacted some of the development organisations that had proliferated in these new republics and offered to write news articles for them in return for bed and board. A few took me up on the offer.

With youthful certainty, rather than any actual financial accounting or a proper understanding of visa systems, I exchanged my earnings and bursary money into new US dollars – for some reason old notes were unacceptable – and stuffed them into my money belt, hoping it would be enough for the trip. I look back now in amazement at my readiness to head off with only the vaguest of plans for where I would end up, and with no contingency plan in case I was robbed. There were no ATMs where I was going, so the cash would simply need to last. I hoped to get as far as China but was relatively hazy about where I’d go after that, thinking I might try to get to Russia and return home on the Trans-Siberian train.

Or not. I wasn’t entirely sure.

In the end, I was persuaded by a New Zealander in Tashkent to avoid Russia completely. He assured me that the Trans-Siberian was just a really long and fairly tedious journey through featureless landscape dotted with the occasional onion-domed church. Much better, he said, would be to head for China and then traverse the Karakoram Highway from Kashgar down to Gilgit in Pakistan and fly out of Islamabad. I took his advice but was to have a near-death experience as a result.

My main concern before I left was that I might run out of books. So, I packed War and Peace in my hand-luggage – an epic novel for an epic journey – and a few other books I was happy to discard along the way. I’d borrowed an old rucksack from my dad, which he said had served him well as a student. It was a mistake. The rucksack was both heavy and uncomfortable and – as I discovered while in a bazaar in Turkmenistan – fairly easy to pickpocket. I also had a Russian phrase book, which might have been useful for ordering opera tickets, but other than that was fairly limited. It was my rusty childhood Turkish that was to prove more helpful.

It was 1996 and a privilege to lift the Iron Curtain and peek behind it, visiting countries just five years old that were coming to terms with their own national autonomy. As these new identities were being forged, there was still a reeling from the sudden collapse of a centralised system which had in no way prepared these former Soviet countries for independence. Even oil-rich Baku was struggling economically, despite the influx of oil companies keen to get drilling.

There were many highlights along the way, and moments I still remember clearly. The first was the thrill of reaching the border between Turkey and Georgia. Turkey felt very familiar, but just a few hundred metres away was a country that had recently emerged from behind the Iron Curtain. I joined the queue and passed through checkpoints fairly quickly on both sides, my passport scrutinised and stamped. There was a bench on the Georgian side where I waited for the bus, feeling nervous excitement at signs everywhere in bold Cyrillic or exotic Georgian script. But my excitement dampened as the hours went by. It was just before dawn when the bus finally arrived. Most of the other passengers were women, and were either traders or prostitutes. They all looked exhausted, and I wondered what money or other services had been extorted from them in order to let them pass. I soon learnt that the Soviet Union, and the new republics it had spawned, survived on the tenacity and determination of Soviet women, who did whatever was necessary to feed their families.

I saw little of Georgia on that first trip; it was only on subsequent visits that I discovered the amazing food and wine, the love of complicated toasts, and the stunning mountain scenery of the country. From Georgia I took another bus, this time to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. There, on the shores of the Caspian Sea, was the classiest of the capitals that I would pass through. The city was divided into three sections. The outer section was Soviet-era and largely grey blocks of flats. The inner section was a walled city, which was as large as Baku would get until the mid-19th century when the city overflowed with foreigners flocking to the world’s first major oil boom. The middle section, or ‘Boom town’, was a cacophony of different European architectural styles built around the same period, as former peasants – now millionaires – returned from tours of Europe with postcards of their favourite buildings, which they handed over to architects to reproduce, along with wads of cash.

Baku was about to experience another oil boom, but it hadn’t quite started. Taxi drivers were still university professors or opera singers, trying to make ends meet now that state salaries were virtually worthless. Those who could got jobs as cleaners or receptionists in the offices of the new international oil companies.

I spent a week in Baku waiting for the ‘daily’ ferry to actually leave for Turkmenistan. Arriving in the dusty port town of Krasnovodsk, I bit into my first slice of Turkmen melon, which was incredibly crisp and sweet, thanks to the searing desert temperatures. Later I learnt that skilled melon growers could even grow their crops in the desert itself, digging down to the root base of a camel-thorn shrub and making an incision into the main stem and inserting a melon seed. Not all would take, but those that did were able to draw on the camel-thorn’s extensive and deep-running root system, producing melons with a unique flavour.

Ashgabat, the Turkmen capital, was a fascinating study in presidential megalomania. Saparmurat Niyazov, the first secretary of the Turkmen Communist Party, had reinvented himself after independence as Turkmenbashi, or ‘leader of the Turkmen’. Everywhere there were slogans stating, ‘People, Nation, Turkmenbashi!’ His portrait was ubiquitous, and his golden revolving statue dominated the skyline. Shops may have had a limited amount of consumer goods, but there was plenty of Turkmenbashi aftershave or vodka (later I regretted not buying a bottle as a souvenir). This presidential cult had barely got into its stride – Turkmenbashi went on to write a holy book entitled The Rukhnama, promoted as equal to the Bible and Quran. Great swathes of this drivel had to be memorised and regurgitated in lieu of job interviews or university exams, or to pass a driver’s test.

After Niyazov died, the presidential cult continued with his successor, who managed to bankrupt the country through further mismanagement before handing over the reins to his son, a prince in all but name. Serdar Berdimuhamedow now rules a country with the world’s sixth largest gas reserves at a time when global gas prices are surging. Despite this, the people of Turkmenistan live in abject poverty. Water and power cuts in the searing summer temperatures are the norm, and most have to queue for hours outside state shops in the hope of buying cooking oil, flour or water. Meat is a mere memory. Unsurprisingly, these repressive and isolationist policies, along with a presidential cult, have led people to draw many parallels with North Korea.

I took a further train through...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Asien |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78578-987-2 / 1785789872 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78578-987-8 / 9781785789878 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 412 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich