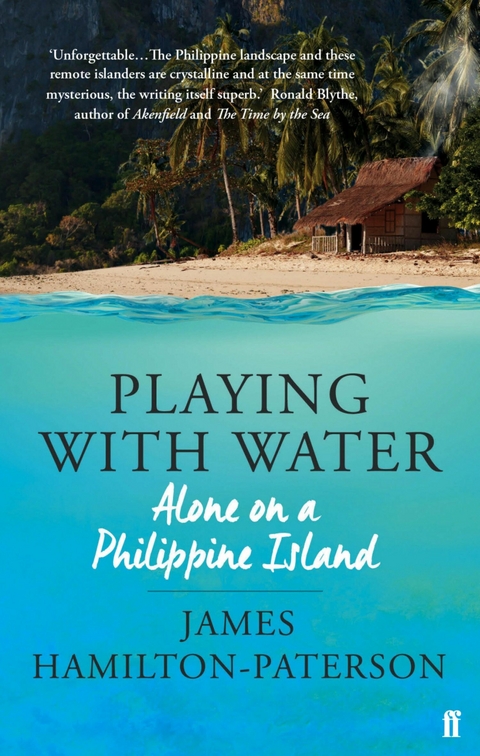

Playing With Water (eBook)

288 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-31400-3 (ISBN)

James Hamilton-Paterson is the author of the bestselling Empire of the Clouds, which was hailed as a classic account of the golden age of British aviation. He won a Whitbread Prize for his first novel, Gerontius, and among his many other celebrated books are Seven-Tenths, one of the finest books written in recent times about the oceans, the satirical trilogy that began with Cooking with Fernet Branca, and the autobiographical Playing With Water. Born and educated in England, he has lived in the Philippines and Italy and now makes his home in Austria.

A classic of travel writing. For many years award-winning writer James Hamilton-Paterson spent a third of each year on an otherwise uninhabited Philippine island, spear-fishing for survival. Playing with Water tells us why he did. Yet it also gives an account of life in that class-bound country as a whole. For it is in places like this rather than Manila of the international news reports that the underlying political and cultural reality of the Philippines may be seen.

James Hamilton-Paterson is the author of the bestselling Empire of the Clouds, which was hailed as a classic account of the golden age of British aviation. He won a Whitbread Prize for his first novel, Gerontius, and among his many other celebrated books are Seven-Tenths, one of the finest books written in recent times about the oceans, the satirical trilogy that began with Cooking with Fernet Branca, and the autobiographical Playing With Water. Born and educated in England, he has lived in the Philippines and Italy and now makes his home in Austria.

When living in Kansulay I commute between the forest and the village by the shore, a distance of only a mile or so but quite enough to tinge things with the remoteness of the interior, the bundok.

The path from Kansulay takes me up a valley whose floor was long ago planted with coconuts. Eventually the path forks off, crosses a stream and climbs steeply up one side among wilder vegetation until it comes out on top of the bare ridge where my hut stands. From here I can look down into the valley without at any point being able to see its floor, only the dense crowns of the palms, infinite sprays of tail-feathers and the coconuts’ amber gleam. Invisible beneath them are two huts several hundred yards apart. One is the house of my nearest neighbours, the Malabayabas family, whom I see almost daily. The other is a ruin and stands by the stream amid the pink-grey pillars of the coconuts. There with several pigs once lived Lolang Mating.

Lolang Mating was undoubtedly an exceptional person by rural Filipino standards in that although she was a grandmother (as the honorific implies) she chose to live alone, away from her family who were down in the village. She was visited daily by her son and her grandchildren who are now muscular teenagers with feet calloused from climbing trees. They came as much to feed the pigs as to see Granny but to all appearances relations between them were reasonably cordial. However, the old woman refused absolutely to go down and live with them. Probably nobody had actually pointed out that it was unseemly for a woman in her seventies to live on her own in the semi-wilderness: it would have been superfluous in a culture where the principle of family proximity is supreme and where the question Who is your companion? is habitually asked whenever any activity such as eating or sleeping or merely walking home is proposed. In a land where nobody does anything alone from choice, where a bamboo floor densely packed with sleeping bodies is considered far preferable to luxurious solitude, where superstition as much as a lack of torch batteries keeps people indoors after dark, Lolang Mating chose to live alone in her hut.

In time I became friendly with her as I went to and from the village for necessities such as rice and cooking oil. When I fetched water from the stream nearby in the mornings I would see her, patched skirts tucked up around bowed mahogany legs and with her grey hair done up in a bun skewered with a bamboo sliver, standing in the current washing her wrinkled chest. With instinctive decorum we would pretend not to have seen each other as I suddenly found something to interest me a little way off. Then she would call out a greeting and I knew I could come and lay my plastic jerrycan on its side in the stream and chat. By now she would have changed her blouse and be washing yesterday’s with an end of bright blue detergent soap.

Those early morning conversations with Lolang Mating became a feature of daily life at Kansulay. We would sit on the low boulders with our feet in the current while the palm fronds combed the sunbeams as they fell on the water and butterflies floated on the air. She would talk and unaccountably fall silent, absently raising and lowering the blouse into the water, sometimes beating it with a paddle hacked from the spine of a frond as if to emphasise an inward voice. She would talk to me of the Japanese Occupation, of the anti-Japanese guerrillas, the Hukbalahap, whom she had once sheltered. She would talk of pigs and murders and Mayor Pascual who had been born without an arsehole – she knew because as the midwife she had delivered him – and the doctor had had to make one with a pair of scissors. She talked about the days when you could shop for a family with a single piso and when almost anyone who wore a proper hat spoke Spanish. She knew a lot about the magicians who lived in the hills of the interior and grew whole fields of tintang luya, black ginger, that rarest of freak plants whose properties were immensely powerful. Black ginger would help you cast spells or defend you against manananggal, vampiric horrors which squat in the rafters of huts where there are babies or the sick and let down their tongues to suck out the sleepers’ livers.

‘So aren’t you frightened here at night?’

‘Of course not,’ she said.

‘But believing in all those spirits and dwarves and ghosts and vampires?’

‘I believe in them of course, I often see them. But I’m not scared of them. They’ll never trouble me. They never have and I’m an old woman now. As long as I’m in my place they’ll leave me alone because they know it’s my place and not theirs.’

‘Like dogs.’

‘Like that.’

She told me she was born here. I looked instinctively towards her hut, its legs and walls bleached silver with age. It was not the house she had been born in, of course, but it was on the same site, as she explained on another occasion. To Europeans accustomed to nostalgia about old things Filipinos can sometimes seem strangely matter-of-fact about impermanence. In an architecture of light wood structures and grass or palm thatch, termites and typhoons between them make a fifty-year-old house an antique. Houses are quickly built and newness is valued as a sign that the family fortunes are on the up-and-up. A patched or sagging house speaks of poverty and low spirits.

Of the house in which Lolang Mating had been born not a trace remained but a blackened rectangular pit where she told me one of its four legs had stood. The original post-hole had been enlarged and was now used as a kiln for making charcoal from coconut shells.

‘When I was born there were no coconuts here,’ she said one day. ‘This was all forest like up there where you live. We had a clearing where my father kept pigs. We found bananas and papayas in the forest and grew kamoteng-kahoy which we carried down and sold in the village. Then our landlord bought the land and decided to cut it all down and plant coconuts. I remember how ugly it looked, the land burnt off and with tufts of coconut seedlings in rows. Now of course it’ll soon be time to cut them down and replant them. They should have been re-planting all the time, not waiting for them to become old at the same moment.’

This spot by the bend in the stream had always been her place regardless of what vegetation came and went, and about it she was not a bit matter-of-fact. She spoke of Kansulay as of some alien city, not as a small collection of houses identical to her own a bare mile away by the sea and lived in almost exclusively by her own relatives of varying remoteness.

‘Too much noise there,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t live in that house of Dando’s’ (Dando was her son). ‘Children and cooking and drinking all the time, day and night. And I don’t like that electric light they want to put in. It hurts my eyes. Too much light at night is harmful: you can tell because it makes people look older, even the children. It does something to the skin. And when you go outside you can’t see anything for five minutes.’

A genuine solitary, then, recognisable at any time and in any culture. The thought was not displeasing that I too might end my days standing in a dappled stream at dawn soaping my wrinkled chest and at night putting luminous fungi in a glass jar to cast a soft radiance inside my hut. One day Lolang Mating was found sprawled on the earth beside her kayuran, the low wood tripod with a serrated flange fixed to its beak used for grating coconuts. She was taken down the track to the village and put to bed in Dando’s house. I went to see her a day or two later. She was ambling about on her tough old legs but as if lacking a pig to feed or a blouse to wash she could no longer remember where she was going. There was talk in the family about ‘high blood’; I assumed a minor stroke. She seemed quite unimpaired but there was a remoteness in her eyes that was new.

‘They won’t let me go,’ she told me. ‘They say I can’t go on living there, I might die there all alone.’

‘I expect it’s for the best,’ I said ritually, but we both knew it wasn’t. She had been born there, why could she not die there among the fireflies and the frogs and the crickets? What was so special about having family faces stare down at you and pester you with medicines?

‘Lazy,’ she said confidingly. ‘They can’t be bothered to come up the track and fetch me down to bury me.’

She made it sound a long way off to her land. It was obvious that had she lived in a world where one did not have to consider social rituals and pious custom she would have chosen to be buried there among the coconuts by the bend in the stream rather than in the cemetery at Bulangan where the salt sea breezes rotted the cement sepulchres and within ten years made them look sordid rather than venerable. She was cut off from the land of her death and quite possibly now at the mercy of an alien crew of territorial spirits. Each time I saw her she seemed more silent, more worn down with the sheer proximity of people.

‘Take her home,’ I urged Dando. ‘Go on, even if it’s only for a visit while you feed the pigs.’

And apparently he did, probably raising his eyebrows to passing villagers’ unspoken enquiries with a mime of filial helplessness as his ancient mother walked back to her country. She was not allowed to do anything when she got there but sat once more in the doorway of her hut with her feet on the polished bamboo rung of the top step as she always had, looking out at the sift of sunlight into her glade and the lurch of butterflies in and out of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.10.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | coral reef • desert island • Philippines • Robinson Crusoe • Survival • Survivor • Tropical Island |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-31400-7 / 0571314007 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-31400-3 / 9780571314003 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 395 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich