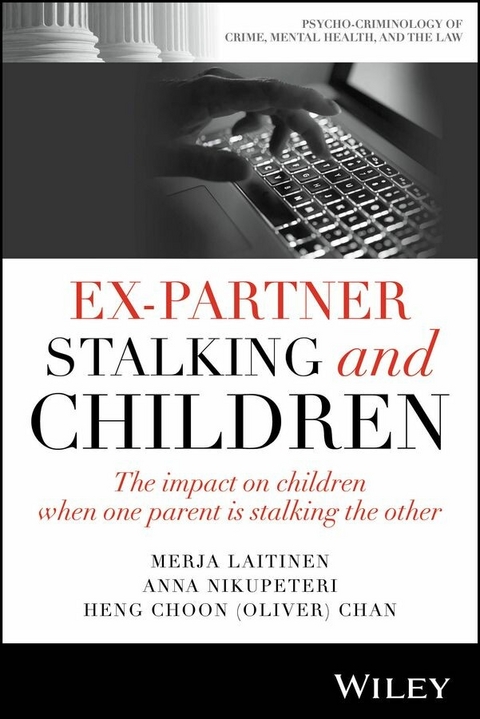

Ex-Partner Stalking and Children (eBook)

290 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-394-18530-6 (ISBN)

PROVIDES AN AUTHORITATIVE OVERVIEW OF STALKING BEHAVIOR PERPETRATED BY PARENTS AND ITS IMPACTS ON CHILDREN

Stalking targeted at one of the child's parents by the other poses a major psychosocial and physical threat to children's wellbeing and security. Although interdisciplinary research on stalking has expanded in recent decades, intimate partner/ex-partner stalking has been viewed as an 'adults only' problem.

Ex-Partner Stalking and Children brings together scholars and practitioners from different disciplines in the field to examine ex-partner stalking as a psychosocial and criminological issue in children's and young people's lives. Providing both theoretical and practical perspectives, this comprehensive volume explores approaches for increasing awareness of parental stalking, addressing its impacts on children and young people, and advancing interventions and methods of support for them.

Throughout the text, the authors challenge existing conceptions of intimate partner/ex-partner stalking as a phenomenon that exists only between the partners, rather than a form of gendered violence that creates a victimizing environment for the children.

A novel contribution to both scholarly and practical understandings of ex-partner stalking, this important book:

- Addresses a gap in knowledge on the socially, ethically, and legally challenging phenomenon of cases when one parent is stalking the other

- Offers insights and tools to help practitioners better recognize, support, and intervene in parental stalking situations involving children

- Examines research findings on stalking behavior, including psychological and trauma perspectives

- Discusses best practices and working methods, challenges in identifying the child's experiences, and factors preventing children from receiving help

- Recommends future directions in promoting children's and young people's rights in ex-partner stalking

Part of the acclaimed Psycho-Criminology of Crime, Mental Health, and the Law series, Ex-Partner Stalking and Children: The Impact on Children When One Parent is Stalking the Other is essential reading for undergraduate and graduate students in disciplines such as criminology, social work, healthcare, psychology, and education, and an invaluable resource for law enforcement staff, nurses, psychologists, therapists, social workers, teachers, and other professionals who work with victims of stalking.

MERJA LAITINEN is Professor of Social Work and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lapland, Finland. Her research interests are violence and abuse against children and women, social work and inter-professional, empowering practices with children, young people, and their families in vulnerable situations.

ANNA NIKUPETERI is Associate Professor of Social Work at the University of Lapland, Finland, and a licensed social worker. Her research focuses on different sensitive target phenomena in social work, the methodological questions behind their study, and how to develop systems that better serve people in need.

HENG CHOON (OLIVER) CHAN is Associate Professor of Criminology at the University of Birmingham, UK. Dr. Chan's research focuses on sexual homicide, sexual offending, stalking behavior, juvenile delinquency, psycho-criminology, and Asian criminology. He is the author of more than 110 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, and eight books.

2

Children as Collateral Victims of Separation/Divorce Stalking

Walter S. DeKeseredy

Anna Deane Carlson Endowed Chair of Social Sciences, Director of the Research Center on Violence, and Professor of Sociology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA 26501

Introduction

It is now well established in the social scientific literature on woman abuse that separation and divorce do not end men’s offline and online violence against women (DeKeseredy et al., 2017; Ellis et al., 2021; Spearman et al., 2023). Consider the recent case of Aaron Steven Romo, a man with a history of violence against women across three American states involving several different women in recent years. While out on bail after being charged in December 2022 with two felony counts of corporal injury on a spouse and false imprisonment, he murdered his ex‐girlfriend, 24‐year‐old Mirelle Mateus, in Anaheim, California, on Friday March 16, 2023 (Myers, 2023). This example of intimate femicide is not a rare instance.1 In fact, the literature on risk factors associated with lethal violence identifies separation and divorce as multiplying the risk of this type of femicide by as much as nine times (DeKeseredy et al., 2017; Walklate et al., 2020). Further, some studies show that after separation from an abusive partner, up to 90% of women experience continued harassment, stalking or nonlethal forms of physical abuse (Spearman et al., 2023).

It is not only women who are risk of being victimized during and after separation/divorce. Threats and endangerment to children are also common (Fischel‐Wolovick, 2018; Henze‐Pedersen, 2021; Stambe & Meyer, 2022). Note that Hayes (2017) found that separated women were four times more likely to experience threats to take and harm children than nonseparated mothers. As described by the aunt of one mother whose male partner murdered her two children:

He was losing power. He was gentle until he couldn’t get his own way. He was obsessed with her and would never let her go, although she tried to get away. Once she left him and moved into an upstairs unit. He came to the place where she was staying and climbed up the wall like a spider, he started to smash the window to break in and so she let him in. He said he would never let her or the kids go. So, she returned.

(Johnson, 2005, p. 53)

In sum, women exiting intimate relationships is often the catalyst for an escalation of violence and diversification of abusive tactics, including stalking, which is why more empirical, theoretical, and policy work on what DeKeseredy and Schwartz (2009) coined as dangerous exists is necessary. Such attention to the impact of separation/divorce abuse on children is also essential to understanding the dynamics and impact of woman abuse. This is vitally important because many professionals who are involved with families at separation/divorce believe that the abuse ends at separation and that child abuse and woman abuse are two discrete phenomena (Dallam & Silberg, 2006). In other words, they do not see women and children as “joint victims of fathers/perpetrators” (Monk & Bowen, 2021, p. 25). What is more, child abuse and children’s exposure to their mothers being beaten, raped, and abused in other ways are often minimized or undetected in family court proceedings, which has long‐term consequences for survivors (Khaw et al., 2021; Meier, 2020; Spearman et al., 2023). This chapter addresses, then, some key issues for children as collateral victims of separation/divorce stalking. It is first, though, necessary to define the terms separation/divorce and stalking because conceptualizing these concepts is subject to much debate.

Conceptualizing Separation/Divorce

Early studies of separation/divorce violence done by O’Brien (1971) and Schulman (1981) sparked relevant contemporary empirical and theoretical work. Yet, the field did not begin to fully develop until the late 1980s, with most of the research coming out of Canada. The bulk of the studies done there were small‐scale, focused on post‐separation violence, and overlooked sexual violence and the abuse of women exiting and trying to exit cohabiting relationships (DeKeseredy & Dragiewicz, 2014). The start of the new millennium brought the term separation/divorce violence for reasons identified here. Consider that leading experts in the field came to the realization that leaving an abusive relationship is a process (see DeKeseredy et al., 2004; DeKeseredy et al., 2019; DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2009), and one that might go forward or backward in fits and starts. It may begin long before anyone moves out or initiates legal proceedings, and it may continue long after the divorce is final (DeKeseredy et al., 2017). Moreover, the victimization of women during and after the process of leaving cohabiting unions became seen as equally important as the harms done to women during and after the process of legal separation and/or divorce. Be that as it may, as of late, a new wave of publications revisits the term post‐separation violence (e.g., Ellis et al., 2021; Desai et al., 2022; Spearman et al., 2023).

Researchers are divided into two camps over the issue of whether people must be living apart to be considered separated. Brownridge (2009), for instance, restricted his analysis to post‐separation violence, which he defines as “any type of violence perpetrated by a former married or cohabiting male partner or boyfriend subsequent to the moment of physical separation” (p. 56). Brownridge’s conceptualization and those of others who use the term post‐separation violence is too narrow. Couples do not have to be living apart in separate households to be separated and divorced, though many surveys of marital rape and nonsexual types of violence against women define separation and divorce this way. This approach is highly problematic because it neglects assaults after women’s decisions and/or attempts to leave while they are locked in relationships (DeKeseredy et al., 2017).

Many women stay in the same dwellings as their male partners but are emotionally separated from them. Emotional separation, a major predictor of a permanent end to a relationship, is a woman’s denial or restriction of sexual relations and other intimate exchanges (Ellis & DeKeseredy, 1997). Emotionally exiting a relationship can be just as dangerous as physically or legally exiting one because it, too, increases the likelihood of male violence, including stalking and sexual assault (Block & DeKeseredy, 2007; DeKeseredy et al., 2017).

The only exit available to scores of women is an emotional one because they have a legitimate fear that their extremely jealous and possessive husbands will harm them and their children. There are plenty of examples in the scientific literature and in the popular media of women routinely hearing their partners say, “If I can’t have you, nobody can,” “You have no right to leave me,” and “I own you” (Adams, 2007, p. 166; Sev’er, 2002). Such threats are often real, with the risk of lethal and nonlethal assaults peaking in the first two months following separation, and when women try permanent separation through legal and other means (Dawson et al., 2018; Dobash & Dobash, 2015; Ellis et al., 2015).

The term post‐separation violence is problematic in other ways. For instance, unlike Brownridge (2009), most researchers who use it do not examine cohabitation outside of the context of legal marriage. This is a mistake because getting “a marriage license probably does not change the dynamic of…abuse within an ongoing relationship” (Campbell, 1989, p. 336). Various studies done over the years have found that cohabiting relationships are at higher risk of both femicide and nonlethal violence than are marriages (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2013).

For the preceding reasons, separation and divorce here means physically, legally, or emotionally exiting a marriage or cohabiting relationship (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2009). Consistent with my earlier work, I focus here on women‐initiated exits because “they are the decisions that challenge male hegemony the most” (Sev’er, 1997, p. 567). As Ellis et al. (2015) uncovered, “[M]ale partners believe they, and not their wives or third parties such as judges and lawyers, are primarily responsible for deciding when they are truly separated or even divorced from the female partners who left them” (p. 2). Regardless of the type of intimate union they want to maintain, numerous men have a “fanatical determination” to prevent their partners from exiting a relationship (Russell, 1990). They use a variety of means to try to “keep them under their thumbs.” Stated at the start of this chapter, sometimes these methods turn out to be lethal, and the motivation may be mixed with some notion of “If can’t have you then on one can” (Polk, 1994).

Sometimes, too, as Spearman et al. (2023) documented in their concept analysis of separation/divorce abuse, these methods entail:

threats to harm or kidnap children,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Psycho-Criminology of Crime, Mental Health, and the Law |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht |

| Schlagworte | ex-partner stalking behavior research • ex-partner stalking children • ex-partner stalking interventions children • ex-partner stalking young people • intimate partner stalking children • parental stalking behavior research • parental stalking phenomena |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-18530-8 / 1394185308 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-18530-6 / 9781394185306 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,6 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich