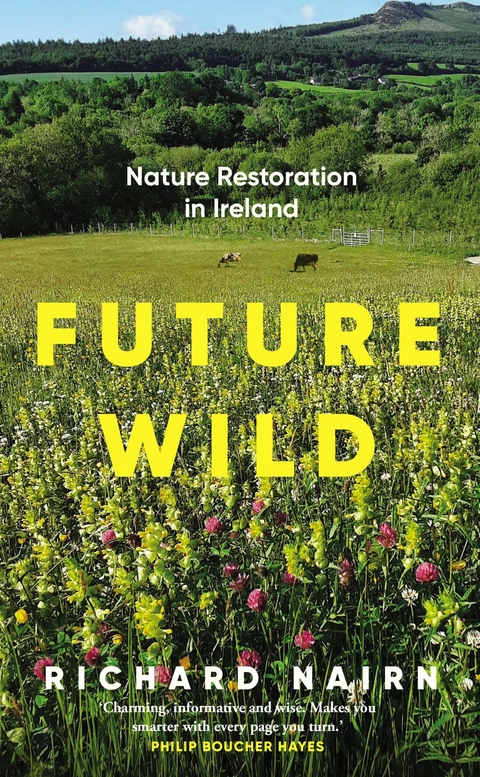

Future Wild (eBook)

256 Seiten

New Island Books (Verlag)

978-1-83594-002-0 (ISBN)

RICHARD NAIRN is an ecologist and writer who has published seven previous books including a recent trilogy on nature in Ireland. He holds a Master's Degree in Zoology and has published many scientific papers. During his long career he worked as a nature reserve warden and was the first National Director of BirdWatch Ireland. He lives on a small farm in County Wicklow which is dedicated to nature restoration. richardnairn.ie

RICHARD NAIRN is an ecologist and writer who has published seven previous books including a recent trilogy on nature in Ireland. He holds a Master's Degree in Zoology and has published many scientific papers. During his long career he worked as a nature reserve warden and was the first National Director of BirdWatch Ireland. He lives on a small farm in County Wicklow which is dedicated to nature restoration. richardnairn.ie

Introduction

I am standing at the front door of the house where I live. It is a bright day in May. The sun creeps up above the ridge to the east as it rises from the sea. Immediately below me is a meadow that sweeps away down the hill, bright with wildflowers in the morning sun. At the bottom of a long hill lies the old woodland where I can hear a woodpecker drumming on a dead branch. Beside it is a burgeoning plantation of native trees that is beginning to merge with the old woodland. I can hear the rushing river in the wood and imagine its winding path through the ancient trees. In the distance is a craggy hill covered in heather and flanked by dark green forest. The sun is lighting up one side of the hill while the other remains in shadow. Over me drifts the first red kite of the morning, effortlessly soaring above the meadow as it searches for its first meal of the day. I am surrounded by nature and beauty.

A decade ago, I was presented with the opportunity to buy this small farm in the valley where I live in the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains. I had always wanted to plant trees, to surround myself with nature and to be able to observe the natural world changing from day to day. Within a year I suddenly found myself with the keys to the gate. It was pure exhilaration to wander at will, to observe the land in all its diversity. The pasture had been grazed by horses and sheep and was shorn to the length of a mown lawn. The patch of old woodland at the foot of the hill was a mysterious, magical place, but the sheep were wintering there and browsing the undergrowth. Deer were also browsing in the woodland and emerged occasionally to graze in the pasture.

Spring is my favourite time of year. All is new in nature after the long cold months of winter when the struggle to survive takes precedence over everything else. As I stand here in the brightening dawn, I celebrate the return of heat from the sun. Blackbirds are singing loudly from the trees all around and wrens belt out their incessant calls from the undergrowth. The meadow is filled with butterflies and bees all working to ensure the next generations will replace them in a short time. They feed on the abundant wildflowers that have returned here since the sheep and horses were removed. Just a short walk from my front door, badgers are sleeping underground, their growing cubs venturing out at sunset to explore the woodland and meadow that their ancestors have known for hundreds of years. A solitary deer stands in the meadow, its ears twitching to listen for danger, ready to race to the cover of the trees. Nature is alive here.

Although it is not a wilderness, but a landscape managed by humans for thousands of years, this is the place that I love. It is like a painting, a panorama that stretches from east to west. I never tire of gazing out to watch the clouds that drift across, sometimes bordered in gold, sometimes carrying the threat of rain that speeds in from the west. At night the moon follows the setting sun picking out the hillside above with a ghostly light. Then I listen to the calls of a family of owls and watch them dodging in and out of our growing plantations. I want to intimately know every wild creature and wild plant here. My aim from the start was to restore nature on this land and make it a refuge for wildlife in a rapidly changing world. The red kite, extinct in Ireland for 300 years, yet now gently drifting across the fields, is a sign that nature restoration can work. I want to give back to nature, as much as possible, the beauty and diversity that has been modified and simplified by landscape change. To live with nature instead of trying to exploit it.

Nature for me is both an inspiration and a refuge. It gives me endless pleasure to immerse myself in the wild places and find there the animals and plants that still live the way they have done for thousands of years. In hard times, such as the recent pandemic, nature provides a safe anchor, its plants and animals changing with the seasons just as they have always done. All through my life, I have worked to protect and restore nature. Half a century ago, I learnt the practical methods when I worked as a nature reserve warden. As a staff member of an environmental organisation, I focussed on birds which are such a beautiful and accessible part of our wildlife. Later, working with other environmental specialists, I strived to prevent damage to nature due to the rapid development of our country. Now, in my retirement, I spend most of my time managing my own small farm with nature restoration as the main objective.

Inspiration and peace are not the only gifts that this little patch of land offers me. It provides the wood for the fire that heats my house in the winter. I spend long hours in my woodshed splitting and stacking logs to season for next winter’s fuel. The sun powers the solar panels on the roof that provide most of the electricity that I need. Rain falling on the same roof drains into large tanks, a free rainwater harvest for the gardens in a dry summer. The soil in the gardens produces a variety of tasty and nutritious vegetables and fruit that will last for the whole year. Season after season, these gifts are generously given by the land that asks nothing in return except care and protection to go on producing. The American writer Aldo Leopold wrote, ‘When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.’1

The land surrounding my farm is not a natural landscape. From my front door, I can see intensive farmland and commercial forestry. I can hear the noise of machinery at a nearby quarry. Repeated ploughing and fertiliser applications have replaced the natural grassland in the valley with cereals and silage fields and confined the wildflowers to little corners that cannot be grazed or cultivated. Chemicals run off the fields into the river, threatening the aquatic life that depends on clean water. The ancient woodlands have largely been replaced by fast-growing ranks of conifers that are repeatedly clear-felled and replanted. Here there are uncontrolled herds of non-native deer, browsing the undergrowth and preventing the natural vegetation from returning.

Since acquiring this farm, I have set about managing it to restore the greatest natural diversity possible in an otherwise intensively managed landscape of farmland and forestry. ‘But why would anyone abandon land to nature on a good productive farm, with fertile, well-drained soils? Why not grow a crop or graze some livestock here? Why leave the meadow alone to flower and set seed when the hay is not used when it is mowed? Why not harvest the old timber in the woodland and plant it with commercial conifers?’ These are questions often posed by critics or doubters. I have made a personal decision to give priority to nature, one that is increasingly necessary in light of the biodiversity emergency that we face right now. I am attempting to restore nature on this small patch of land or, rather, to help it to restore itself. If the heavy pressures of modern land use are removed, natural succession will start to kick in.

Every gardener knows that if you dig a patch of garden and then go on your summer holidays, the ground will be covered in weeds when you return. Thistles, nettles, docks and many other smaller wild plants will reclaim this space. These native wildflowers are simply plants in the wrong place, opportunists that fill the space left by any disturbance of the ground. Richard Mabey described them as ‘part of nature’s immune system, of its instinctive drive to green over the barrenness of broken soil’.2 If you abandoned your home altogether, the disturbed patch would quickly sprout with brambles, buddleia or gorse. If nobody moved into the property, within a year or two, scrub would be filling the garden, closing off paths, scrambling over fences and blocking windows. Small mammals would move in, hedgehogs might shelter in denser patches and foxes might make a den beneath the old garden shed. After a decade of ‘neglect’, young tree saplings would be pushing through the thorny scrub, reaching for the sunlight. The tree seeds would have fallen in the autumn, blown from mature trees in surrounding gardens or hedges, germinating and pushing up through the soil in spring. If the garden was completely abandoned to nature, it would become woodland after 20 or 30 years. This is a form of natural succession that happens before your eyes. But we rarely want this to overwhelm our beloved gardens. The continual disturbance involved in gardening interrupts the process of natural succession and moves it back to an earlier stage. It reduces the diversity of wild plants and animals and ensures that only those species that we favour can establish.

If cultivation or grazing is abandoned on farmland, as sometimes happens when the land is unproductive or the farmer gets a job elsewhere, brambles push out from the surrounding hedges and, within a year or two, shrubs and trees begin to establish in the fields. Again, natural succession is moving the fields back to woodland, mimicking a time before humans began to clear the forests and farm the land. Similarly, if grazing pressure by sheep and deer on mountain land is reduced, first heather and then trees will start to return and the succession to woodland begins again. Many other modern land uses – drainage of rivers and lakes, exploitation of peatlands, quarrying hillsides, turning sand dunes into golf courses, dumping on coastal saltmarshes or building roads and urban developments – interrupt natural succession, removing wild plants and animals and impoverishing biodiversity. All of these...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Recht / Steuern ► EU / Internationales Recht | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Öffentliches Recht ► Umweltrecht | |

| Schlagworte | Bord na Móna • Climate • climate change • conservation • diversified habitats • Ecology • ecosystem • Environment • eu restoration law • extinction • farming • forestry • Habitats • intensive land use • Ireland • native species • natural habitats • Natural History • natural resources • Nature management • Nature restoration • Rainforest • Rewilding • Richard Nairn • rural Ireland • sustainability • Wicklow • wildlife • Wild Shores • wild waters • Wild Woods |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83594-002-1 / 1835940021 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83594-002-0 / 9781835940020 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich