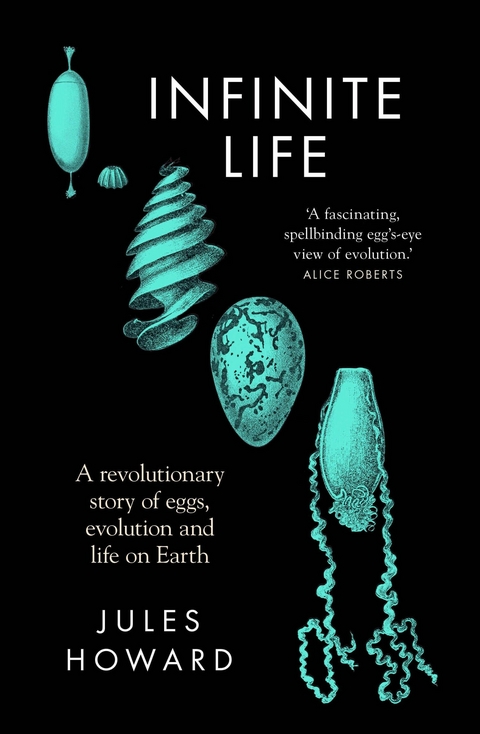

Infinite Life (eBook)

288 Seiten

Elliott & Thompson (Verlag)

978-1-78396-778-0 (ISBN)

Jules Howard is a zoological correspondent, science writer and broadcaster, whose recent book, Wonderdog, won the 2022 Barker Book Prize for non-fiction. He writes on a host of topics relating to zoology, ecology and wildlife conservation and appears regularly in BBC Science Focus magazine and on radio and TV, including BBC Breakfast and Radio 4's Nature Table and The Ultimate Choice. He lives in Northamptonshire with his wife and two children.

Every animal on the planet owes its existence to one crucial piece of evolutionary engineering: the egg. It's time to tell a new story of life on Earth. 'Jules Howard's egg's-eye view of evolution is dripping with fascinating insights' ALICE ROBERTS'So much passion and poetic prose' BBC Radio 4, Inside ScienceIf you think of an egg, what do you see in your mind's eye? A chicken egg, hard-boiled? A slimy mass of frogspawn? Perhaps you see a human egg cell, prepared on a microscope slide in a laboratory? Or the majestic marble-blue eggs of the blackbird?Every egg there has ever been, is an emblem of survival. Yet the evolution of the animal egg is the dramatic subplot missing in many accounts of how life on Earth came to be. Quite simply, without this universal biological phenomenon, animals as we know them, including us, could not have evolved and flourished. In Infinite Life, zoology correspondent Jules Howard takes the reader on a mind-bending journey from the churning coastlines of the Cambrian Period and Carboniferous coal forests, where insects were stirring, to the end of the age of dinosaurs when live-birthing mammals began their modern rise to power. Eggs would evolve from out of the sea; be set by animals into soils, sands, canyons and mudflats; be dropped in nests wrapped in silk; hung in stick nests in trees, covered in crystallised shells or secured by placentas. Whether belonging to birds, insects, mammals or millipedes, animal eggs are objects that have been shaped by their ecology, forged by mass extinctions and honed by natural selection to near-perfection. Finally, the epic story of their role in the tapestry of life can be told. 'In a book that brilliantly evokes past eras, Howard provides a new perspective on the history of life on Earth.' The Mail on Sunday

1

DUST FROM DUST

Hadean Eon, 4,540 million years

ago, to the end of the Cryogenian

Period, 635 million years ago

‘But if (and oh what a big if) we could conceive in some warm little pond with all sort of ammonia and phosphoric salts, — light, heat, electricity present, that a protein compound was chemically formed, ready to undergo still more complex changes . . .’

– Charles Darwin, in a letter to Joseph Hooker (1871)

Among the billions of stars taking shape in our galaxy long ago, the yellow dwarf sun that would come to light our days would not have immediately stood out as anything unique. In the long view, it was just part of a constellation, nothing more. Another pinprick of light, born from a spinning disc of super-heated matter, like almost everything else. Out of the planets that formed around this disc, one single rocky sphere near the middle of the pack started to develop differently to any other we know about so far in the universe. On Earth, the sun energised oceans and continents. Our planet soaked up its radiation and things started to stir. In time, life would evolve here. And with it, in the life lineage that would become animals, came the egg.

How far back does the egg go in Earth’s history? Right to the start? Not quite. At first, 4.5 billion years ago, this place was barely a planet at all. It was more like a condensing cloud forming from debris – ice, rock, dust – that circled our fledgling star. It was an aggregation of matter, one of many aggregations orbiting our Sun. Earth would have looked like a misshapen blob in those earliest millennia, pulled out of shape by the gravity of the objects caught in its grip. But as this sphere grew, its gravitational pull increased and, slowly, it became rockier.

There was nothing gentle about those early Earth days. Not a single rotation passed without the bombardment of new rocks and ice and new showerings of space dust. Some chunks of rock were as big as countries are today, some as big as continents and some, rarely, were even bigger still. Although the explosions caused by their impact were violent and tumultuous, these intemperate collisions, without any thought or forward planning, delivered the precursors for life – the elements, especially metals, that would become the building blocks of proteins and the structural units of cells and their membranes. These gifts from the solar system are in you now. Many comets in this early period delivered ice, which vapourised upon impact. In our paper-thin atmosphere, water molecules grouped together again, coalesced and, for the first time, formed beads at the mercy of gravity. Clouds formed. Rains fell. There was something akin to weather.

Cauterised through millions of years of bombardment, the Earth’s surface became a hellish melting pot, but there was no stopping the maelstrom of chemical interactions now. Elements shuffled against one another to form minerals which would go on to become extra ingredients in life’s cauldron. Unstable isotopes of uranium sank deep into the Earth, stoking a fire that still rages beneath our feet today, and the potential of carbon, an atom which can unite with other elements in multiple arrangements, was being explored through a trillion or more chanceful, random interactions. Some carbon arrangements held for moments. Others, in the form of the oldest diamonds, were forged 100 kilometres below the Earth’s crust at temperatures of up to 1,200 Celsius and they are still locked in their arrangements as you read these words.

In that first few hundred million years, Earth’s atmosphere was gossamer thin. Yet, as its crust hardened, gases began to belch out from the chaos churning kilometres beneath. These gases burst upwards through turbulent volcanic eruptions, through cracks and fumaroles. In the sea, chemicals boiled from vast seams that must have looked like open wounds in the ocean floor. Some of these produced ocean vents, where water heated from deep underground thrust itself upwards into the cold ocean waters. Here, where hot met cold, minerals in the water deposited themselves into tubes that loomed upwards like monolithic organ pipes in a vast cathedral.

The Earth is one character in this, our setting of the stage for the egg. But there is another character too. It is Luna – our moon.

Luna also has history. It begins as a cosmic congealment of dust caused by an explosive collision unrivalled in our history, when Earth was struck by a planet-sized object named Theia. Some 6,500 kilometres wide, Theia is likely to have had its own molten core and, perhaps, water. After engaging itself with Earth’s orbit, Theia glanced across the face of the planet, at close to a 45-degree angle. This happened very early on in our history, perhaps only a few hundred million years after the Earth began to form. The collision could so easily have been a near miss. The cloud of debris that formed after the connection of these two celestial objects was so great that, once pulled back into shape by the workings of gravity, it became our Moon. The collision affected the Earth forever, knocking its rotation off its axis, causing it to spin at an angle. From this point onwards, Earth would spin 23.5 degrees off kilter. This is the first of a number of flashpoint moments for the egg, for this wonky spin meant that our planet ended up with an exaggerated seasonal change – spring, summer, autumn, winter. Seasons bring with them chaotic periods of ebb and flow; feast and famine; life and death. And in time, eggs would evolve in ways that would navigate animals, and their genetic material, through hard times like these. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. For billions of years back then, life was mostly about relentless reproduction – single-celled organisms dividing and dividing, throwing variations to the anarchy of the oceans; a sea of losers, speckled with accidental winners, dodging the certainty of uncertain environmental change.

Evidence for these early micro-organisms abounds in numerous forms, many going back 3 billion years or more. This evidence comes from biogenic graphite, loosely described as the fossilised remnants of early cells left as chemical imprints on graphite and carbonate, dug out of rock faces by geologists. Littered within these samples are carbon arrangements derived from organic reactions common to life today. Evidence also comes from garnet crystals, formed in the Earth’s earliest pressure-cooker environments, that contain carbon molecules preserved in a chemical death grip with other atoms seen commonly in biological systems today. These biological arrangements are composed of oxygen, nitrogen and even phosphorus, a common component of cell membranes and internal cellular components, including DNA. Indeed, rock impressions from the Pilbara region of Western Australia contain pyrite-bearing sandstones that have within them micro-fossils of tube-like cells once thought to oxidise sulphur using a primitive form of photosynthesis. Life was, to turn a phrase, finding a way 3.7 billion years ago.

But there were no eggs or anything much like them at that time.

There is evidence from 200 million years later than this – an eyeblink in evolutionary terms – of cement-like structures (made by micro-organisms) known as stromatolites. Stromatolite colonies were so large back then that they could have been stood upon like giant slimy toadstools, protruding from coastal pools and lagoons. Like weary soldiers, survivors of evolutionary wars untold, these ancient organisms remain in a handful of tidal lagoons today (most famously at Shark Bay in Australia) where salinity remains so high that grazing animals such as sea snails stand no chance of sustaining a slimy foothold. These glistening, bulbous stromatolites are formed from centuries of microbial growth, each generation building upon the last in an orgy of photosynthesis. But, again, eggs remain absent from this diorama of early life.

By 1.9 billion years ago, cyanobacteria were thriving. Gorging on sunlight and producing energy for growth in the presence of carbon dioxide, these micro-organisms flourished in surface waters. Great clouds of oxygen, their waste product, began to cause our atmosphere to change. Minerals in rocks exposed to the atmosphere began to oxidise, stripping oxygen atoms from the atmosphere to create flaky red deposits rich in iron ores that are still found today. The Earth’s surface, literally, started to rust. Oxygen levels rose. The colour of our planet changed. Within another evolutionary blink of the eye, these photosynthetic organisms had painted parts of the Earth’s surface in greens, reds and blues, giving life to water in slimy mats upon the shores. Through cyanobacteria, for the first time, the planet Earth had been endowed with signature colours visible from light years away.

These vast populations of cyanobacteria, many trillions strong, started to evolve. Through accumulations of mutational copying errors, individuals and their populations became slightly different from one another and it was upon this variation that the cogs of natural selection bit. As the sun’s radiation poured across the Earth’s surface, the rate of these copying errors waxed and waned. With each incoming deluge of photons, the broad-brush forces of natural selection set to work, removing from the gene-pool those most ill-equipped for survival. Seasons must have come and gone like impeccably timed plagues back then. And in the shadow of their retreat, the ones that were left – the toughest, the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Schlagworte | Alice Roberts • Almanac • animal • Biology • bird • Birth • Cat Bohannon • chris packham • Darwin • David Attenborough • Dawn Everything • Dinosaur • earth • Ecology • Ed Yong • Egg • entangled life • Eve • Evolution • godfrey-smith • Graeber • Guide to the Night Sky • Guy Shrubsole • halliday • How to Read Tree • Immense World • Incredible Unlikeliness of Being • insect • interesting facts for curious minds • jordan moore • Jules Howard • Kerschenbaum • Lia Leendertz • Life • life on Earth • Lost Rainforests of Britain • Mammal • Natural History • Natural selection • Nature • Night Sky Almanac • Otherlands • OTHER MINDS • Parikian • Planet • Planet earth • Popular science • Sapiens Harari • Sapolsky • Science • Sheldrake • Storm Dunlop • Taking Flight • Tristan Gooley • wildlife • Wonderdog • Zoology |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78396-778-1 / 1783967781 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78396-778-0 / 9781783967780 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich