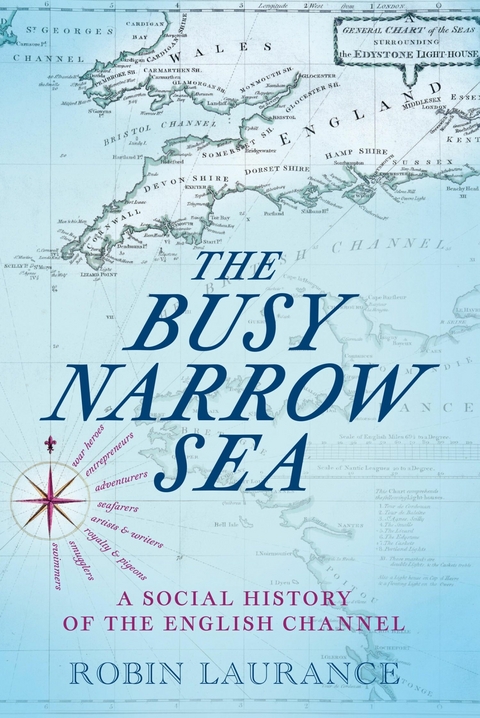

The Busy Narrow Sea (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-683-7 (ISBN)

As a freelance writer, Robin Laurance honed his research and writing skills contributing features to The Times, The Guardian, The Sunday Times and a variety of weekly and monthly magazines. These features have taken him from the Oval Office in Washington to the car factories of Japan; the sugar estates of Brazil; the Presidential Palace in Turkey, and the coconut plantations of southern India. He spends his leisure hours on boats, and guiding visitors round the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

1

When Britain First Left Europe

When Britain first left Europe half a million years ago there were no politics involved: it did so by the force of nature. Before the parting, you could take a Sunday afternoon stroll from England, across Siberian-like tundra, to the European continent and then walk back again before dark. It would not have been a particularly interesting trek across a land bridge with little vegetation. You would not have met anybody on the way, but you might have encountered mammoths and the occasional elk, and you would have got your feet wet crossing the river that ran through the valley.

And then there was a catastrophic flood – a mega flood created by much greater forces than prolonged and heavy rain. Earth scientists believe that the land bridge that joined Britain to the Continent at what is now the Channel’s eastern end had formed a dam holding back the waters of a huge lake fed by the waters of the rivers Thames, Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt, with ice from the mountains of Scandinavia and Scotland forming the lake’s eastern and northern boundary. Evidence for the lake comes from glacial-like sediments found in the coastal areas of south-east England and on the continental coast where Holland meets Germany. The Cambridge Professor Philip Gibbard, an expert on the Channel’s birth, suggests that the water level in the lake was about 30m above current sea levels and was held back by the land bridge that joined England to the Continent.

It was about 450,000 years ago that the waters of the lake began to spill over the land bridge, filling the valleys on its western side and creating what Gibbard calls a ‘channel river’, and a very narrow beginning of the Dover Straits. Erosion caused the river to widen gradually over the next 300,000 years, until the next mega flood occurred when a second ice sheet in the southern North Sea created a new lake which was dammed to the south by a land ridge north of the Dover Straits.

When this weaker dam burst, the flood was catastrophic. Sanjeev Gupta and his colleagues at Imperial College London studied data from the examination of the Channel floor, which showed grooves indicating that it was once exposed to the air and then subjected to an enormous deluge of water. This evidence of vast quantities of water cascading from the southern limits of the North Sea was what scientists had been waiting for.

Land on both the northern and southern sides of this new torrent of water was eroded, and Britain became an island. Its history had been defined by the forces of nature; not until the opening of the Channel Tunnel could you once again walk (in theory) to the continent of Europe from England’s green and pleasant land.

‘Nature has placed England and France in a geographical location which must necessarily set up an eternal rivalry between them,’ wrote Napoleon’s spin doctor, Jean-Louis Dubroca, in 1802. How right he was. The two kingdoms kept apart physically by the waters of the Channel have been kept apart by long-established cultural differences, peppered by outbursts of pique. And when the French decided they had had enough of kings, the Republic proved no better friend to their cross-Channel neighbours.

Robert Tombs, a Professor of French History at Cambridge University, writes:

Geography comes before history. Islands cannot have the same history as continental plains. The United Kingdom is a European country, but not the same kind of European country as Germany, Poland or Hungary. For most of the 150 centuries during which Britain has been inhabited it has been on the edge, culturally and literally, of mainland Europe.

There are no marker buoys defining the extent of the Channel, but by general consent the Straits of Dover mark the eastern end, and a line between Land’s End and the Île Vierge, off the Brittany coast, defines the point where the Channel meets the Atlantic Ocean. Altogether, this is a stretch of about 350 miles. The massive granite lighthouse on Vierge rises nearly 100m above the ground and is the tallest in Europe. The first Longships Lighthouse, on the rocks off Land’s End, was also built of granite in 1795. The modernised automatic light now has a helipad on the top.

Known originally as the ‘Narrow Sea’, the British now call this stretch of water the English Channel, although nobody is entirely sure why. Early Dutch sea charts refer to it as the Engelse Kanaal, and English statesmen would, at an early stage, have wanted the French to be in no doubt about who had sovereignty over the water. The French call it La Manche (the sleeve). On days when the sea is angry and giant freighters are crowding the space as they fight to meet ever-more demanding schedules, ferry captains crossing the freighters’ path call it something else altogether. Separation lanes keep the eastbound and westbound traffic apart, with the eastbound, fully laden ships taking the French side. But in the Straits of Dover, where the ferry crossings are at their most prolific, there are just under 22 miles between the chalk cliffs of Dover and Cap Gris-Nez, squeezing the traffic lanes and demanding the unflinching concentration of helmsmen.

That unflinching concentration required of helmsmen was clearly absent when the cargo ship Mont-Louis sank in the Channel in 1984 after colliding with a German vessel in thick mist. The collision raised worrying questions about the cargoes carried through the narrow seaway. The French authorities claimed the ship had left Le Havre with a cargo of medical supplies, but, on persistent questioning from the environmental protection campaigners Greenpeace, admitted the cargo was not medical supplies but barrels of uranium hexafluoride. The Mont-Louis had been heading for Riga in the Soviet Union, where the uranium was to be enriched. There were no fatalities as a result of the collision, and the cylinders of uranium hexafluoride were recovered intact.

The Channel is classed as international waters. The 12-mile Territorial Sea Convention applies until the Dover Straits, where there are less than 24 miles between the French and English coasts. The two countries share responsibility and management for this stretch of the Channel, and for the 500-plus commercial ships that pass through the straits every day. (There was a time when the range of territorial waters was measured by the distance travelled by a shot fired from a cannon on the shore.)

The Channel weather is notoriously fickle. Fog and heavy rain that reduce visibility and winds that regularly reach gale force test the best of seamen. But the shipping forecast, broadcast four times a day by the BBC, does at least provide warnings of what is to come. This forecasting for shipping around the British Isles was conceived after a fatal storm off the Welsh coast in 1859 claimed 130 ships and the lives of 800 sailors. As a result, Robert Fitzroy, who had captained Charles Darwin’s Beagle, was moved to pioneer a system of telegraphed warnings of storms to harbours around the British Isles – a system that grew into today’s Meteorological Office. The Met Office divides the Channel into four regions – Dover, Wight, Portland and Plymouth – advising ships’ captains of predicted wind directions and force, and likely visibility. And BBC Radio 4 broadcasts the information at four precise times during the day on behalf of the Maritime and Coastguard Agency.

Tides are strong in the Channel. High tide at Plymouth comes some seven hours after high tide at Dover. At Calais, high tide comes five hours before Saint-Malo. And as the tide rises and falls it creates tidal currents. Tidal ranges – the difference in height between low and high tide – differ greatly. At Dover it is about 17ft; at Brighton it is nearer 19ft 6in. The Bristol Channel experiences a rise in water levels of some 30ft, while at Saint-Malo it can reach 26ft. (It climbs to just under 40ft in the Minas Basin of the Bay of Fundy on Canada’s Nova Scotia coast.) Just beyond Saint-Malo, the tidal range at the mouth of the Rance river reaches a full 35ft, which prompted the French electricity company EDF to build the world’s first tidal barrage across the estuary. Its twenty-four turbines generate enough tidal power in a year to satisfy the needs of a town the size of Rennes with its population of 217,000.

Spring tides, which have nothing to do with the seasons, occur when the earth, sun and moon are in alignment and the gravitational pull of the sun adds to the pull of the moon. The oceans bulge more than usual and tidal heights increase. Seven days later, when the three are out of alignment, the high tides are a little lower and the low tides a little higher. These are referred to as neap tides. In the Channel during spring tides, tidal currents flow at terrifying speeds through the Alderney Race – the funnel between the island and Cap de la Hague on the north-western tip of the Cherbourg Peninsula. Yachtsmen have logged the current at 12 knots (22km/hour), which is fine if you are going with the tide but to be avoided at all costs if you are coming the other way.

The Channel tides proved too much for Julius Caesar. Coming from a part of the world that sees very little tidal movement, the tides in the Channel confused him. After his failed first crossing, he made a base for himself at Boulogne, where he ordered the building of hundreds of landing craft. In all, he had gathered 800 ships, which were made ready at their moorings on the River Liane, just upstream from Boulogne. With some 17,000 men and 2,000 horses, he set sail at sunset one summer evening in 54 BCE. But the tidal currents in the Dover...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Schlagworte | Alderney • A Social History of the English Channel • Boulogne • Brittany • Channel Islands • channel islands occupation • channel sea • channel swimmers • Channel Tunnel • D-Day • Dunkirk • Great Britain • Guernsey • Ice Age • invasion of England • Jersey • La Manche • La Maunche • Mor Breizh • Normandy • northern france • River Exe • river tamar • River Test • Sark • Seine • somme river • Southern England • strait of dover • the Channel • White Cliffs of Dover |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-683-8 / 1803996838 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-683-7 / 9781803996837 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich