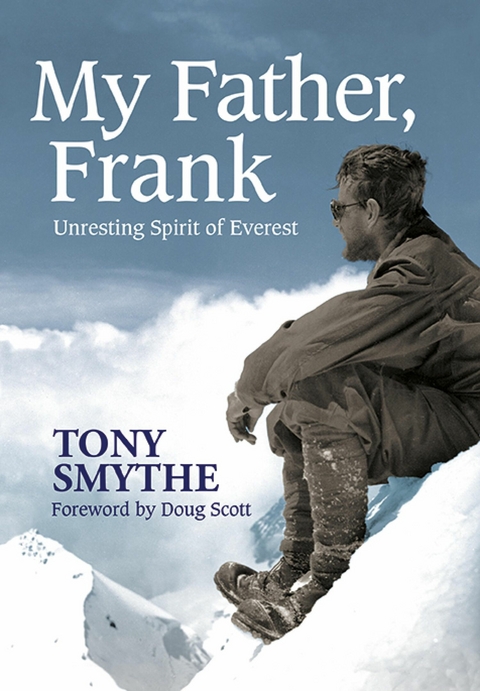

My Father, Frank (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-898573-88-3 (ISBN)

Introduction

My father, Frank Smythe, born in 1900, had huge obstacles to overcome on his way to becoming probably the best-known climber and mountaineering writer of his generation. His father died when he was a baby and his mother went into a self-imposed exile, obsessively clinging to Frank throughout his early life. His schooling was a disaster. He was pressured into training as an engineer, work he hated. When that career failed his half-hearted efforts to make a fresh start in the Royal Air Force also collapsed. At the age of 26, an unskilled job loomed.

However, he had become good at the one thing he really enjoyed — climbing. Much of this had consisted of risky trips into the Alps on his own during engineering training in Austria and Switzerland, but he had survived to reach a high level of expertise, coping even with difficult and dangerous routes on rock, snow and ice. He also had a talent for writing about his adventures. He supplied stories to magazines. His first book was published. With the reluctant support of his mother, his chosen career in which climbing produced material for writing and writing paid for more climbing began to take shape.

In the process there were problems. He upset some senior members of the Alpine Club, who disliked the spectacle of a fellow member making money out of their gentlemanly pastime. And many in the climbing fraternity also felt that it was better to write for other climbers, not the general public. Traditionally it was bad form too, to let emotion play a part in the description of your climbs.

But Frank could never restrict himself in this way. All his life he wrote instinctively for the ordinary man who knew nothing about mountains, putting across his experiences with such conviction that a reader might easily feel he was there on the mountain too. It worked that way for me when I began to read his books as a boy. I felt the pain of frostbitten feet and the exhaustion, yet exhilaration of getting to the top of Kamet, the highest summit in the world reached at that time. I pictured the terrible ice avalanche on Kangchenjunga that killed an expedition Sherpa, and the simple heartfelt ceremony when his crushed body was consigned to a glacier grave before the party’s retreat. Then there was Mount Everest, when Frank climbing alone got to within a thousand feet of the summit — a record height and an achievement that takes its place among the great moments of mountaineering history. More than once I read his description of how he slipped on the steep snowy rocks near the top of the Great Gully. And each time I vividly imagined myself hanging from my clutched ice axe, saved by its pick wedged in a crack above the yawning 8,000-foot drop of the north face.

He went on seven expeditions to the Himalayas, including his visit to the now-famous Valley of Flowers in Garhwal, a place of sublime beauty where he botanised and made outstanding climbs on the surrounding unexplored peaks. He became a highly regarded mountain photographer and ten albums of his pictures were published. He wrote a total of twenty-seven books within the space of twenty years, he lectured intensively, and his resulting popularity led to a level of fame and celebrity that in the days before television and the internet seems remarkable. However like most public figures of that era — the 1930s and 1940s — he kept the rest of his life strictly private. His writings were a blend of wonderful detail in the climbing and travel, tense descriptions of moments of difficulty or danger, a constant search for more profound ways of conveying his feelings for mountains, and wry humour at his own fallibility. But of his life at home and work he revealed almost nothing.

He died at the early age of 48 of cerebral malaria, a deadly strain of the disease, contracted on a trip to India in 1949 when I was 14. In the aftermath he was a hero to me. I was proud of his achievements and became a climber myself. I even, like him, lectured about my journeys and expeditions and wrote a book about climbing. It was sometimes suggested that I ‘trod in my father’s footsteps’, and I dutifully agreed. But as the years passed I acquired a more thoughtful appraisal of him.

For although my two brothers and I had always admired him we’d never been able to form any kind of relationship, except perhaps in unremembered early childhood. After his marriage to Kathleen and the birth of each of us, our life together as a family had been disrupted by his absence on expeditions. And I was only four when he separated himself from us permanently after his marriage broke down. He left us to live with Nona, a nurse from New Zealand, whose own marriage had also failed. In those days divorce tended to be seen as shameful, so in my earlier years I pretended my famous father had not deserted us. Eventually I got over this, realising that Frank’s marriage to Kathleen had probably been doomed from the start; they had been completely unsuited to one another. I started seeing him much as others saw him — a celebrated mountaineer who published a large number of books. But I also knew that his private life had been chaotic with great heartache for himself and those close to him.

I’d always turned down the idea of writing the story of his life. I was too busy, and the job seemed too daunting. But in 1999, when the mountaineering publisher Ken Wilson was putting together an omnibus of some of his books, I changed my mind. Harry Calvert’s book, Smythe’s Mountains had been published in 1985, but that dealt purely with his climbs. I knew there was so much more to be said about the man, his character and the private life behind his achievements. And the succeeding years of research became a fascinating voyage of discovery, adding to what my brothers and I knew already.

He narrowly missed being selected for the 1924 Everest expedition, the attempt when Mallory and Irvine were lost. He was sent to Argentina to work for a telephone company, but finding the job oppressive simply walked away and boarded a ship home, leaving his family to pick up the pieces of his broken contract. He rode the footplate as a fireman on the Southern Railway during the General Strike. After making two superb new routes on the Brenva Face of Mont Blanc — climbs that were the gateway to the rest of his mountaineering career — he fell out with his partner on the rope, Professor Thomas Graham Brown, and a bitter feud developed between them that split the Alpine Club and rocked the mountaineering establishment. A letter he wrote to The Times complaining about the film industry’s reluctance to accept the movie he shot of his expedition to Kamet because of the lack of ‘love interest’ resulted in a summons by King George V for a private viewing of the film at Buckingham Palace (followed by a glass of whiskey with the King in his study). After that the film was accepted without further ado and became a runaway success for months to come in cinemas nationwide. He published a book about just one of his Everest expeditions — that in 1933 — but wrote plenty more about his companions during his three visits to the mountain, in diaries and letters that could not be aired in his lifetime. He planned three private expeditions to Everest; all were overtaken by events. He spotted Mallory’s body through a telescope 63 years before it was found, but never disclosed this for fear of an ‘unpleasant fuss.’ He had several publishers, the Managing Director of one of them becoming a close family friend and Trustee to his Will. He obtained the help of a spiritualist to cure a severe digestive problem after a car crash, later communicating directly with her source, a seventeenth-century Sindh poet. Earlier his extraordinary psychic capacity had saved the lives of a group of men in a Bradford foundry. He was deeply involved in the later years of World War Two, commanding the training of elite mountain warfare troops, in Scotland and Canada, although he eventually suffered a severe breakdown in his health. After the war he invited my two brothers and me to join him and Nona in Scotland, a fascinating experience when at last we came face-to-face with the father we had never known.

His life was as much about his friends and climbing partners as the mountains he climbed. Geoffrey Winthrop Young, one of the most influential figures in British mountaineering had become a mentor to him when he was struggling to make a start as a writer. There were other renowned elders he had turned to in the absence of a natural father — Ernest Roberts of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club during his early climbing in the Lake District, and in the run-up to Everest in 1933 the near-legendary Sir Francis Younghusband, explorer, soldier and leading player in the Great Game.

The list of interesting men he knew well goes on: the Everest leaders General Charles Bruce, Hugh Ruttledge and John Hunt. Colonel Philip Neame, VC, a climbing companion in the Bernese Oberland. Arthur Hinks, the formidable Royal Geographical Society Secretary for 30 years. And even his adversary Graham Brown should be included, a distinguished Professor of Physiology with a large following.

There were many other climbers who were with him in the mountains. Some of them are now significant figures in mountaineering history: Jim Bell, Eric Shipton, Graham Macphee, Colin Kirkus, Bill Tilman, Tenzing Norgay, Jack Longland, Noel Odell, Howard Somervell, Günther Dyhrenfurth, Ivan Waller. As custom required, they stayed largely out of sight as personalities in Frank’s published writing. Clearly a biography was an opportunity to change that.

He loved hills and spent much of his short life among them. Despite his slight, even frail physique his determination and energy were awesome. Enduring fearful hardship at...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.10.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-898573-88-3 / 1898573883 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-898573-88-3 / 9781898573883 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich